From taboo to talk: Using music, dance, trivia and debate to destigmatize mental health in rural areas

We analyze a successful program to promote mental health awareness in Kenya through dance, trivia, debate and lived experience sharing.

Youth Mental Health Challenges in Kenya

Between 2008 to 2017, the number of suicides reported in Kenya rose by 58%. While it is difficult to gather data on suicide rates, data from the World Bank estimates current suicide mortality rates in Kenya at 9.1 people per 100,000.

The Kenyan government views mental health as a priority but reducing the number of suicide cases is a complex challenge because Kenyans who experience mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder face several barriers in seeking help, especially those who are young.

1. Insufficient mental health professionals

First, there aren’t enough mental health professionals in the country. For a country with a population of about 53 million, there are just 100 psychiatrists and 400 psychologists. Although there are trained psychiatric nurses and support staff in rural communities outside of major cities, the typical ratio of these nurses and staff to people is 1: 100,000.

“These staff are typically stationed in the community health clinic for one day of the week and there is often a long queue of people waiting to see them on that day, with some even traveling 25 km to seek help. It is just not sustainable,” said Judah.

2. Treatment is not affordable for the average youth

Second, seeing a mental health professional is expensive and out of reach for the average Kenyan youth. A visit with a clinical psychologist costs approximately 5,000 Kenyan Shillings ($32 US Dollars) and patients typically visit with them at least four times for treatment. Therefore, the minimum treatment cost incurred is 20,000 Kenyan Shillings ($128 US Dollars).

With the average monthly wage for a young person aged 15 - 29 years old being 10,000 Kenyan Shillings, this means that they have to fork out two months of wages, not including transport and the costs of medicine, to see a psychologist.

Many youths end up having to save for months to seek professional help or rely on their parents to foot the bill, which can quickly drain the family’s finances. While there are many private insurers who could support the costs of treatment, most people living in poverty do not have this insurance.

Subsequent consultations are usually slightly cheaper than first consultations. For Singapore citizens and permanent residents, the subsidized rate is typically around S$20 to S$40 ($14 - $29 USD). Non-citizens and non-residents pay full fees, which can range from S$172.80 to S$267.84 ($128 - $199 USD).

3. Stereotypes towards mental health prevent people from seeking help

Third, stereotypes towards mental health conditions are still significant in rural areas, who associate it with witchcraft. Youths who exhibit symptoms are conflicted as to whether to tell their family and worried about their families being unsupportive.

Kenyan men are almost 3 times more likely than women to complete suicide, with data showing that 9.1 men in every 100,000 complete suicide, compared to 3.2 women in every 100,000.

“Culturally, Kenyan and many African societies believe that men are the providers who are strong and dependable. They hesitate to seek help for fear of being seen as weak and there are not many places for them to express themselves, so they drink to cope,” said Judah.

The lack of trained professionals, economic barriers to affording treatment and ingrained stereotypes all create a vicious cycle that prevents persons with mental health conditions from seeking help, eventually leading to them making irreversible decisions in times of crisis.

Solution: Banja, an activity to promote mental health awareness

As a teenager, Judah had personal experience of depression and chose not to seek help. “Other people were depressed because someone had died or they were living under conditions of war. I felt that my reason wasn’t valid,” he recounted.

Eventually, he came to realize that everyone’s experience of pain is different and acknowledged the validity of his pain. His time in University coincided with the sharp rise of suicides in Kenya and he started to see people dying because of mental health conditions.

After experiencing depression for the second time, it prompted him to share his story of overcoming depression to inspire others that there is hope of recovery despite the limited support structures.

“Hope is a valuable currency and I wanted to give that to people,” Judah said.

Because he was studying Information Technology, he was able to connect persons with mental health conditions to telehealth providers, improving their access to treatment.

But he quickly realized that for hope to be sustainable, mental health systems need to change. “Ultimately we have to significantly increase the ratio of mental health professionals to citizens and enact policy changes which bring down the cost of treatment, but this will take a while,” he said.

In the meantime, he started working for Basic Needs, a Kenyan non-governmental organization (NGO) that supports persons with mental disorders and their caregivers to live and work successfully in their communities.

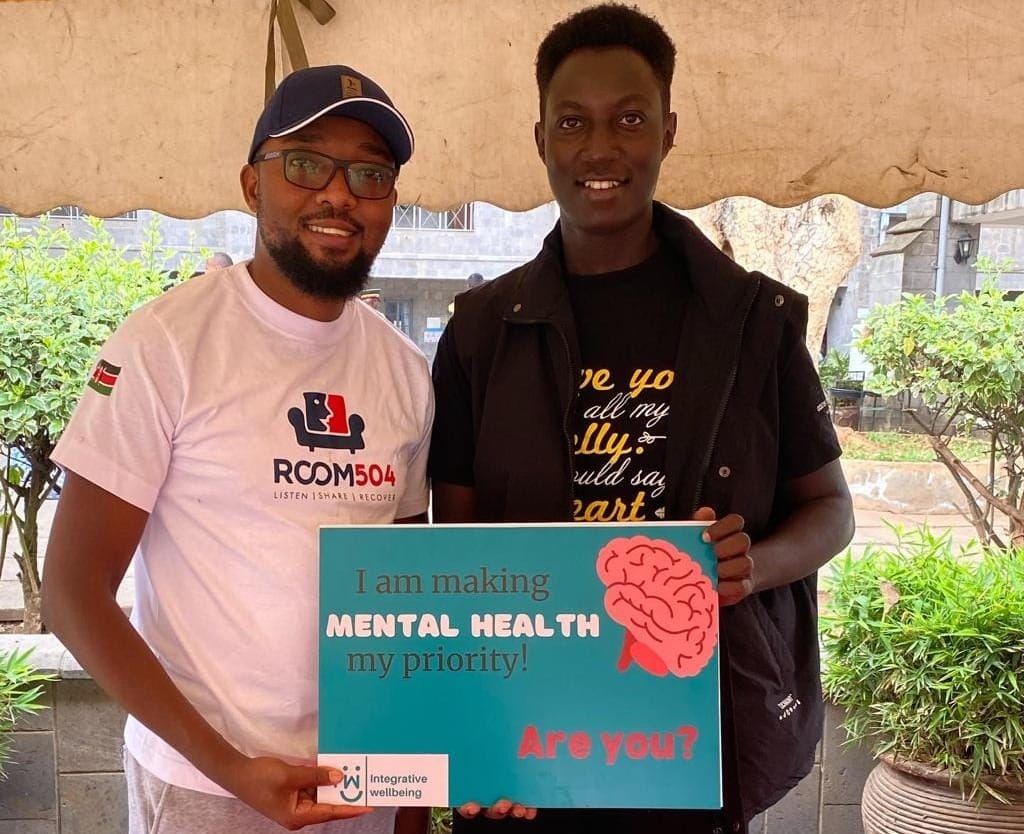

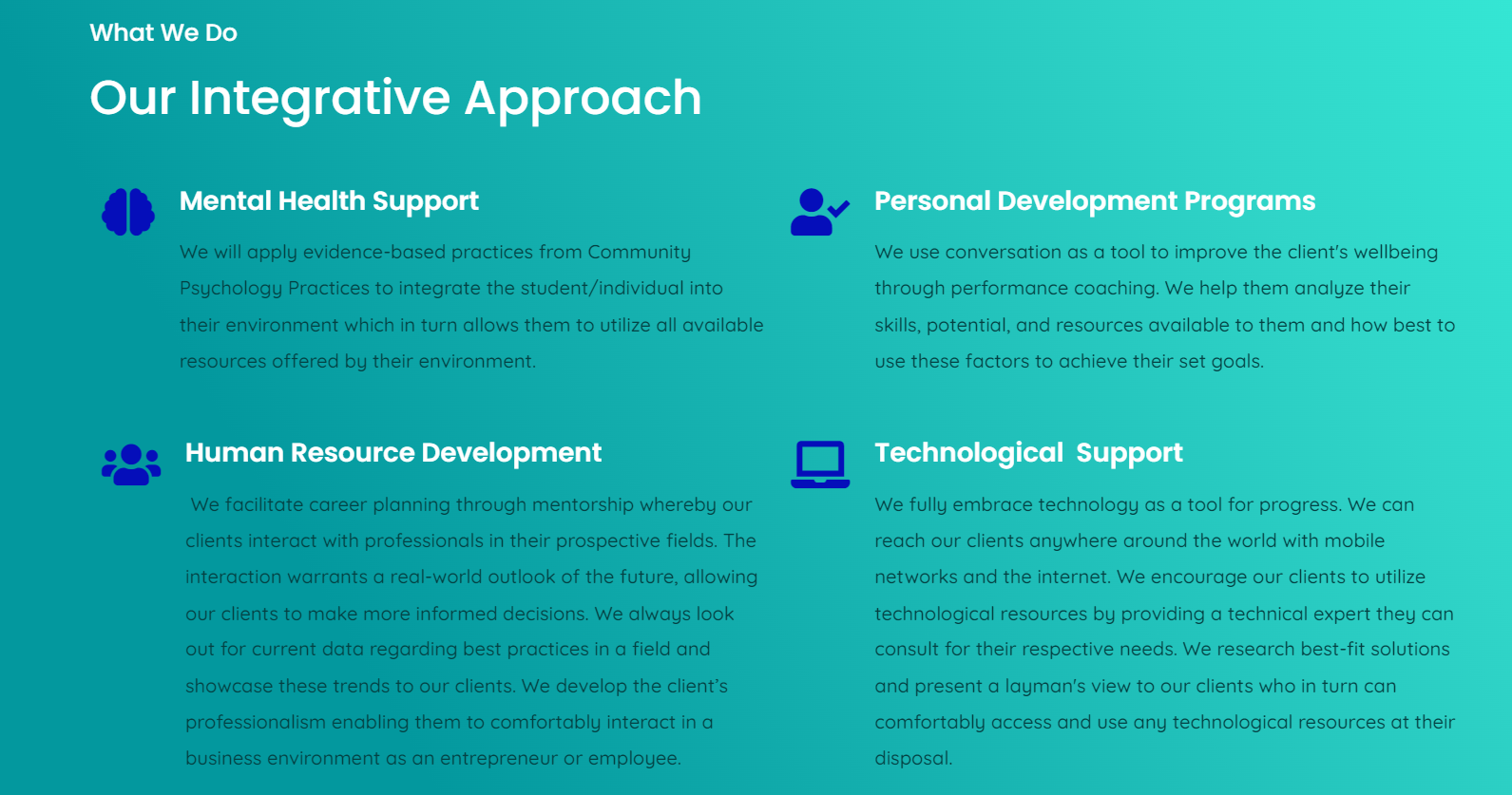

He also founded a mental wellness start-up called Integrative Wellbeing (IW) which focuses on designing programs for youths and training them to run their own mental health projects.

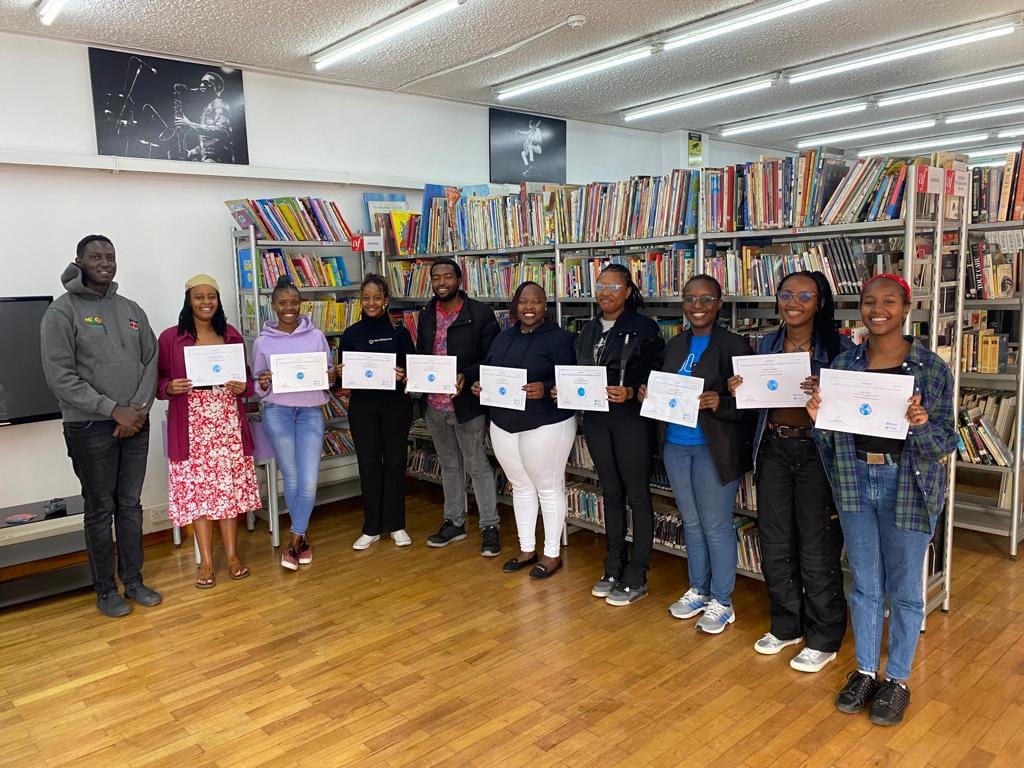

“Youths find it difficult to engage with NGOs who run country level projects because most of them just want to run a small scale mental health project in their school. So we train them in mental health knowledge and give them confidence to start,” said Judah.

IW developed a youth-focused program called Banja (a colloquial term for young people meaning Let’s Talk), that sought to raise mental health awareness in rural communities through entertainment and sharing of lived experiences.

Banja is a whole-day event that is held with participants living in rural communities, with the first 40 mins of the event recorded and shared on YouTube and local television stations.

Banja has 4 components:

- Music & Dance - participants sing and dance along to pop songs, alongside mental health professionals like psychologists and persons with lived experience, who sometimes serve as the DJ and emcee.

- Trivia & Debate - next, participants compete in a variety of trivia questions around mental health, with the winner receiving prizes like cash, branded items or household goods. For example, questions such as: “Which year was suicide decriminalized in Kenya?” are asked.

Often, answering these questions may reveal some misinformation that participants have received in the past and this enables them to learn about stigmatized topics and correct their beliefs in a fun way. Besides answering questions, participants are also grouped into teams that debate statements such as whether suicide should be decriminalized. - Sharing of lived experiences - then, they invite Mental Health Champions trained by Basic Needs to share their lived experience of a mental health condition (e.g. bipolar disorder) that is prevalent in that particular community.

This helps to dispel stereotypes towards what a person with a mental health condition looks like. “The participant just saw this person dancing and had some fun interactions with them. So it helps the participant to understand that a mental health condition is something that people experience and can recover from,” said Judah.

- Connect to services - the last phase in Banja connects participants to mental health services where needed. Many people who come to Banja are friends of persons with mental health conditions and in this segment, they learn about the services available in their communities and beyond, so they can be better allies for their friends.

“Support from a trusted friend can be more effective in encouraging the person to take meaningful actions for recovery compared to a professional,” said Judah.

Impact Measurement

Banja measures its impact through a few metrics:

- The number of people attending the Banja sessions

- The number of people who reach out to Integrative Wellbeing expressing a desire to learn more at the end of the session or to start a support group for their community

- The number of partners in the community they have engaged through the process of facilitating a Banja session

Best Practices

How to get youths to attend

Youths have so many things they can do like studying, hanging out with their friends or playing games. How has Judah been so successful in getting youths to come to his Banja sessions? Here is what he did:

- Identify existing youth groups and work through them to get participants - before bringing Banja to any community, Judah and his colleagues spend a few weeks living in the community. They talk to people in the community such as those working in local government, shopkeepers and community health promoters to understand the mental health needs of the community and the existing support systems that are available.

They start to identify trusted leaders who have access to an audience and a structure for meeting regularly, such as leaders of youth sports teams or book clubs. These leaders help recruit people to the Banja session and increases the likelihood of follow through to access mental health services after the session.

- Showcase projects that youths are working on - youth unemployment is high in Kenya but there are entrepreneurial youths doing amazing things such as making sustainable charcoal for sale. Judah gives youth participants airtime to share about their products when Banja is being recorded.

The episode is later uploaded onto YouTube and shown on television stations, giving these youths and their products some publicity. “They see us as sincere partners and this encourages them to come,” said Judah.

How to create a safe space for meaningful sharing

Once the youths are there, Judah does the following to create a space for meaningful sharing and exchange between professionals and participants:

- Remove barriers of professional - client relationship - Banja works because it enables professionals and participants to connect as human beings having fun. “Most mental health conversations in Kenya come from a perspective of the professionals knowing best and the community doesn’t know,” said Judah.

Sharing the experience of dance removes the barriers of a professional-client relationship and this makes participants more receptive to hearing and engaging with mental health messages later on.

The trivia and debate segment further reinforces this. Even if participants disagree with professionals on topics such as whether depression is an actual illness or a sign of weakness, they feel empowered to express their view because a debate is an exchange of ideas.

“We can correct misconceptions and stereotypes only if people express them. The debate format encourages people to share what they are really thinking and engage meaningfully with a professional as equals. On top of all this, it is fun and you can win a prize,” Judah added.

- Provide training before people share their lived experiences - the Mental Health Champions sharing their lived experiences at the Banja sessions go through a training program where they learn knowledge about mental health, including: the various mental health conditions and the mental health landscape in Kenya.

They are also trained on how to share their story in a meaningful way and how to receive harsh feedback or difficult questions. Afterwards, they are put into a community of practice that supports them as they share their lived experiences. - Develop mechanisms to protect persons with lived experiences - before a mental health champion can be trained, they must feel like they are at a stage of their healing journey where they are okay and have an existing support system they can go back to.

This is something that Basic Needs screens for when selecting Mental Health Champions. “In our experience, it is very difficult to share meaningfully if you are still struggling. We encourage champions to share from their scars which have healed, and not their wounds which are still open and hurting,” said Judah.

Another way that Banja protects its mental health champions is through having a codeword. “If the mental health champion suddenly feels overwhelmed or triggered when sharing their story, they will say they need to eat a banana. That is the cue for our staff to support and ease them off the stage, without causing any distress or embarrassment for them,” Judah said.

How to break stereotypes

Some youths come to the Banja sessions with deeply entrenched stereotypes of mental health conditions that they learn from their communities or misinformation on social media.

Judah believes the way to break these stereotypes is not to give people more information but to help them examine misconceptions they may have in a safe, non-threatening way.

“We can’t change anyone’s mind but we can help them discover new information that may lead them to choose to think differently,” he said. Here is what he does:

- Encourage participants to conduct research to form perspectives themselves - answering questions in the Trivia segment of Banja requires participants to do research on their phones to find answers. For example, doing research on a question about when suicide was decriminalized helps participants discover it was decriminalized rather recently in 2018 and not in the 1960s as many might have thought.

This becomes an entry point for participants to engage in the Debate segment on topics related to mental health such as “should suicide be decriminalized?” or “is depression real?” Rather than being told what is right, participating in this debate requires participants to do research in their teams to learn about arguments they can make and find evidence to support those arguments.

Often, they come across evidence that contradicts stereotypes they have and start to change their minds. “Because they want to win the debate, participants find stories from their communities that will support their argument and this is far more powerful than me as an outsider telling them what is right and wrong from mental health literature that features mostly examples from abroad,” said Judah.

Judah has found such experiential learning methods to be very powerful advocacy tools, with conversations continuing even after the Banja sessions and that is the impact that he wants to create. “They go on to have conversations at the dinner table with their families or at the coffee shop with their friends and those are the real conversations that shift mindsets in rural communities towards mental health,” said Judah.

- Suspend judgment and listen for sources of misinformation - Banja once had a man who seemed very informed about mental health, the importance of self-care and how to seek help. “He was like an A student, until we explored different types of mental illness and he said depression is a disease caused by men sleeping with women because women carry the depression gene,” said Judah.

Instead of correcting him, Judah and his facilitators stayed silent, inviting other participants to respond to his claim that depression is a gender based disease. When asked by the other participants where he had learnt this knowledge, the man said he had learnt it from a channel on TikTok.

This started a healthy discussion where others stepped in to share their view that depression is not a sexually transmitted disease and cited information from research they did or professionals they knew. The mental health champions who were there also shared their stories and experience with depression to help further correct these misconceptions.

“We don’t judge them for believing in misinformation or stereotypes but encourage curiosity to listen in to where they learnt these misinformation and stereotypes because as advocates and professionals, those are the weak points in the community where we want to strengthen,” said Judah.

He also believes that intervening could discourage the next person to share and it is more powerful when misconceptions are corrected by people in their communities whom they know.

What if someone refuses to change their stereotypes or misconceptions? Judah thinks that is ok. “All we ask is for them not to impose their perspective on others but we encourage them to question how they learnt that perspective and this plants a seed which hopefully enables them to see other perspectives."

Do you have lessons or reflections to share from a youth mental health / wellness that you have run or been a part of? Please share them with us in the comments section below - we'd love to learn from you!

Featured Changemaker

Judah Njoroge Wambui is a Mental Health practitioner specialized in Teen & Youth Mental Health. As a depression survivor, he was fueled to form the Youth against Suicide project in 2017, through which he has been able to save over 150 lives. He uses evidence-based practices such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy but allows space for emerging therapies and personal preferences to be able to co-create sustainable solutions with his clients. As founder and program manager for Integrative Wellbeing, Judah has experience creating mental health solutions by amplifying lived-experience voices and by encouraging meaningful community participation.