Best practices for youth civic engagement

How to make civic engagement fun for youths to want to take part? Read on to learn what Corina discovered through years of designing civic engagements for young people to dialogue with decision makers.

Civic participation is essential for a functioning democracy, extending beyond voting every four years. For example, citizens can contribute ideas to improve neighborhoods, share experiences with policymakers or apply for grants to implement projects.

Research shows that diverse participation (e.g., older adults, youths, people with disabilities) leads to more inclusive societies and better policies.

Additionally, civic participation enhances individuals' intellectual capabilities, deepens their understanding of community issues, and fosters a sense of purpose and meaningful relationships, improving their quality of life.

One key group of people to engage are youths

Engaging youths is vital because they have the biggest stake in the future. About 73.6 million young people (15 - 29) live in the European Union (EU), making up 16.4% of its population. Recently, European youths have led influential protests like #FridaysForFuture and #MeToo to advocate for better environmental policies and support for survivors of sexual assault and harassment.

In 2019, increased youth voting contributed to a 25-year high turnout of 50.6%, at the EU elections though they still are less likely to vote than their parents and grandparents. Despite the importance and benefits of civic participation, several challenges prevent youths from participating.

Young people don’t connect voting and politics with creating change

While the youths Corina interacts with care about issues like climate change, education access, social mobility, mental health and the labor market, they are disenchanted with politics and don’t see voting or running for office as effective ways to enact change.

Instead, they prefer to voice their opinions on social media and attend protests, believing their activism alone can make a difference. The lack of young politicians further alienates them from voting, with only two Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) under 30 in the 2019 - 2024 legislature, representing just 0.28% of all MEPs, far below the global average of 2.91% of parliamentarians. Across individual EU countries, this figure ranges from 0.3% of MPs 30 years and under (Greece) to 13.6% (Norway).

This age gap likely contributes to politicians struggling to engage young people effectively, pushing them further away from voting. “We emphasize to young people that not voting reduces incentives for politicians to focus on policies that benefit them. While activism and entrepreneurship are important, change also needs to happen at the ballot box,” she said.

NEET youths face challenges with participating

Youths in NEET situations (not in employment, education or training) often do not engage with civic participation programs, yet their voices and lived experiences are crucial. NEET youths face diverse challenges, such as dropping out of school, living in extreme poverty, being undocumented immigrants or single teenage mothers.

These circumstances make it difficult for them to survive, let alone participate in civic processes. Governments might lack data on them, making engagement even harder.

In 2014, Corina worked with UNICEF and Romania’s Ministry of Social Affairs on a research project to understand NEET youths. This initiative aligned with the EU’s development of financial instruments like the Youth Guarantee. “We partnered with social workers in their communities, engaging them one by one through door knocking, which proved effective, especially in remote areas,” she said.

Migrant youths in western Europe also face challenges with participating, but in a different context

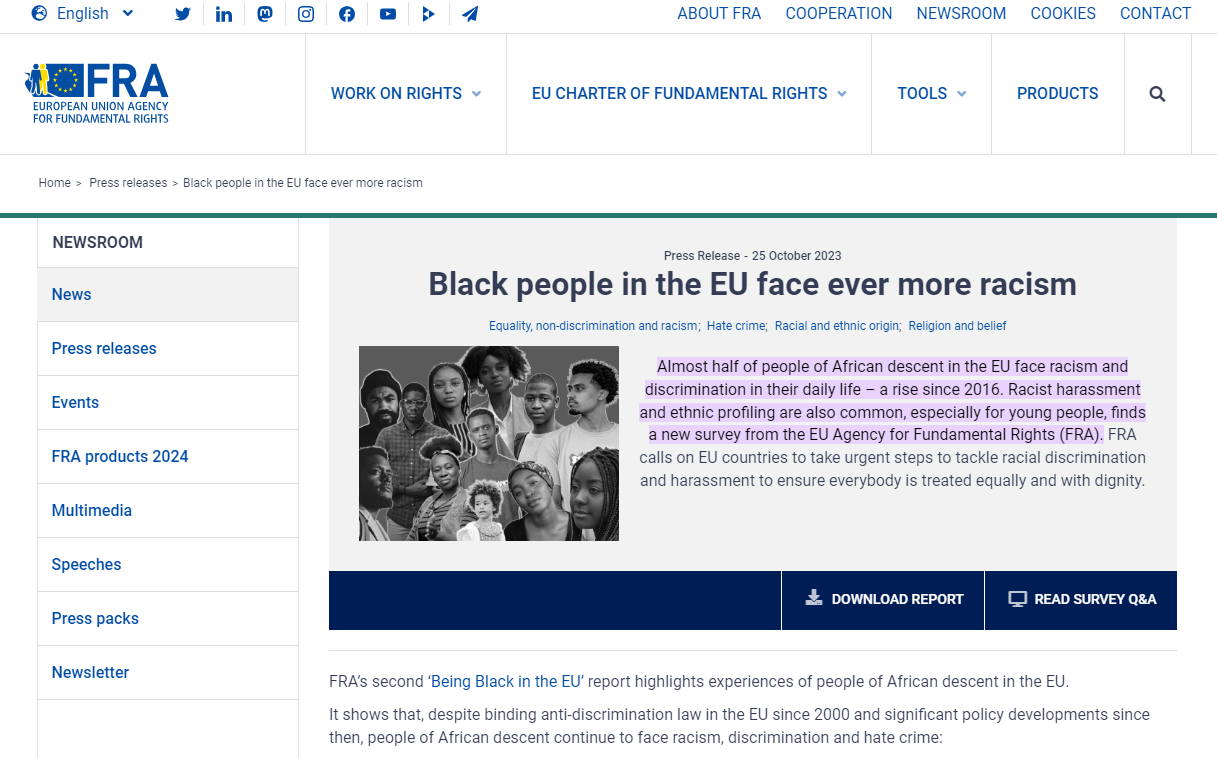

Discrimination against young people with a migrant background and their dependence on employment to remain in the EU often trap highly educated migrant youths in low-skilled jobs. Western Europe tends to avoid addressing racism in public conversations.

Without citizenship, they cannot vote, leaving politicians with little incentive to advocate for them, Nor can they run for political office to change things. From working in a multicultural, yet segregated city like Brussels, Corina observed that migrant youths of African descent were eager to participate in civic processes.

While they typically avoid youth engagement programs designed for European youths, they often exhibit an entrepreneurial mindset, aiming to create social enterprises or non-profits to help fellow African migrants. However, they struggle to access funding and resources compared to white-led organizations.

“Having an African / Arab-sounding last name is an invisible barrier for people to have access to jobs, participating in politics or accessing grants,” said Corina.

Changemaker's Story

Corina was first exposed to civic participation as a young person

Corina was born during the Communism era and grew up in post-Communist Romania, a time marked by corruption and distrust in public institutions like the judiciary and hospitals. Access to resources often depended on personal connections.

Despite coming from a modest family, she was curious about the world and believed in her ability to create positive change for her community. Her attitude stemmed from participating in democracy-related projects piloted by international donors in Romania.

“Looking back, those experiences of getting involved in community life at an early age were life-changing for me. They gave me a sense of obligation to contribute and make things better,” she added.

During Romania’s early years of democracy, international donors helped establish structures and institutions necessary for democracy. One such donor helped set up a local youth council in Alexandria, her hometown, as part of a nationwide effort to educate municipalities and politicians on the importance of youth participation and provide frameworks to encourage it.

At 14, Corina began her civic participation journey by volunteering with the youth council to assist Alexandria’s municipal government in engaging youths. She was selected through a process similar to municipal elections, having to run campaigns to convince her peers to vote for her in elections organized in high schools across Alexandria.

Once elected, Corina and her fellow youth organizers gathered young people at City Hall to identify challenges and initiate projects. These included environmental activities to clean and plant trees in the city forest, hosting cultural events to celebrate special festivals and most notably, organizing a Theatre Festival with and for adolescents, attracting young actors from all over Romania.

This initiative continued for years, teaching Corina the importance of collaboration with youths, teachers, local government officials and parents to create more spaces for civic participation.

Her interest in civic participation continued to grow after experiences in her youth

Her interest in civic participation deepened during her time at the National University of Political Studies and Public Administration, where she studied political philosophy, economics and international relations.

In 2012, she co-founded Social DOers, a volunteer-driven think tank advocating for policies that promote youth participation in peace-building, conflict resolution and decision making processes in Romania and the EU. In 2015, as part of her Community Solutions Program Fellowship, she worked with Chicago Votes, a US-based non-profit, to organize campaigns encouraging youth participation in elections and civic life.

Through these experiences, her interest in youth engagement grew, particularly in finding ways to engage more youths in civic life.

Featured Solution

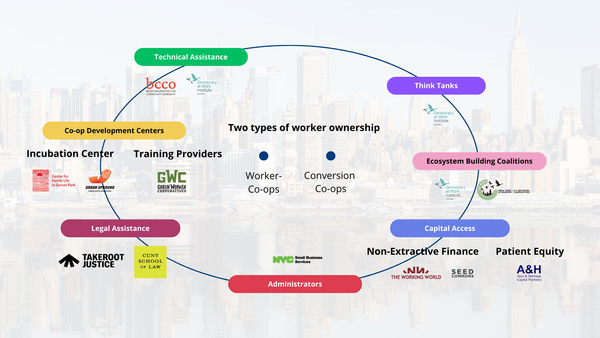

Community Level with Chicago Votes

A voting project with Chicago Votes, where she organized campaigns and public debates to encourage youth participation in elections and civic life, including a National Registration Day which engaged 50 volunteers to register almost 1,300 youths to vote, while educating them about their candidate options. She also visited high schools to give lectures on democracy and voting rights to graduating seniors about to turn 18.

National Level with the European Union Youth Dialogues

As part of the European Union Youth Dialogues, the EU’s largest structured citizen participation process, Corina traveled to four major cities in Romania to facilitate dialogues between municipal leaders and youths, on issues that concern them; such as the availability of meaningful job opportunities, quality of roads and city infrastructure and social rights.

Her efforts included engaging local officials on youth affairs and conducting multi-day training for youths to explain how local governments work and methods they could use to hold government officials accountable. The insights from these dialogues were compiled into a national report for Romania, which was sent to the EU.

Impact Measurement

Measuring impact in civic engagement is challenging for Corina because the effects are often long-term. “It’s similar to education; you only see results years later if you invest for a sustained period of time. It takes time to build a culture of participation, which leads to engaged citizens who hold institutions accountable and therefore, stronger institutions,” she explained.

Grant applications typically require metrics like the number of participants, their demographic profiles (e.g. lower socio-economic backgrounds or first-time participants of such civic engagement activities) and the number of repeat participants.

Some EU projects also estimate social impact by calculating the financial value of hours contributed by volunteers and participants. For example, 50 volunteers and participants contributing 200 hours, in a country where the minimum wage is €10 per hour, can generate €2,000 in social value.

Best Practices

It is crucial to intentionally prepare youths and officials before the activity so that their engagement is constructive

Corina learnt that effective civic dialogues require preparation. In the EU Youth Dialogues, she often found that municipal leaders and youths might not be accustomed to engaging with each other.

Municipal leaders might have only ever consulted ‘experts’ in their policies while youths could feel intimidated by the official titles of these leaders and be unsure of what to say.

To address this, Corina organized half-day workshops before roundtables between youths and the Mayor or a civil servant handling the portfolio of youth and social affairs. These workshops covered:

- Basic public speaking skills so youths can clearly and persuasively communicate their concerns and ideas to the Mayor and active listening skills so they can understand the Mayor’s perspective

- Understanding the structure and key processes of the local government, the roles and responsibilities of the Mayor and how decisions are made

- Help youths to identify, prioritize and articulate the issues they care about and the Mayor or civil servants can address. For example, the Mayor may not be able to influence the education system because that is not in his portfolio.

Sometimes, civil servants attended these workshops to better understand the youths they would engage with. By preparing both sides, Corina ensured more productive and constructive dialogues, a crucial step towards building a culture of democracy.

“The worst thing an organizer can do is to throw both sides into a meeting without preparation and expect meaningful outcomes,” she said.

Facilitating the actual engagement

Beyond preparation, Corina suggests holding dialogues in youth-friendly spaces, like youth clubs, and arranging the room so the Mayor sits at the same level as the youths, and not on a podium where he may be elevated. “These small details make a huge difference in how comfortable youths feel with expressing themselves and the quality of the dialogue,” she said.

She also emphasizes the importance of concluding dialogues by informing youths of follow-up steps, such as attending public City Hall meetings, to encourage youths to stay engaged.

Involving local media to cover the dialogue is another best practice that Corina recommends for its dual benefits. First, it keeps officials accountable to implement what they said at these dialogues and second, media visibility enhances their commitment to engage with youths.

Make civic participation fun

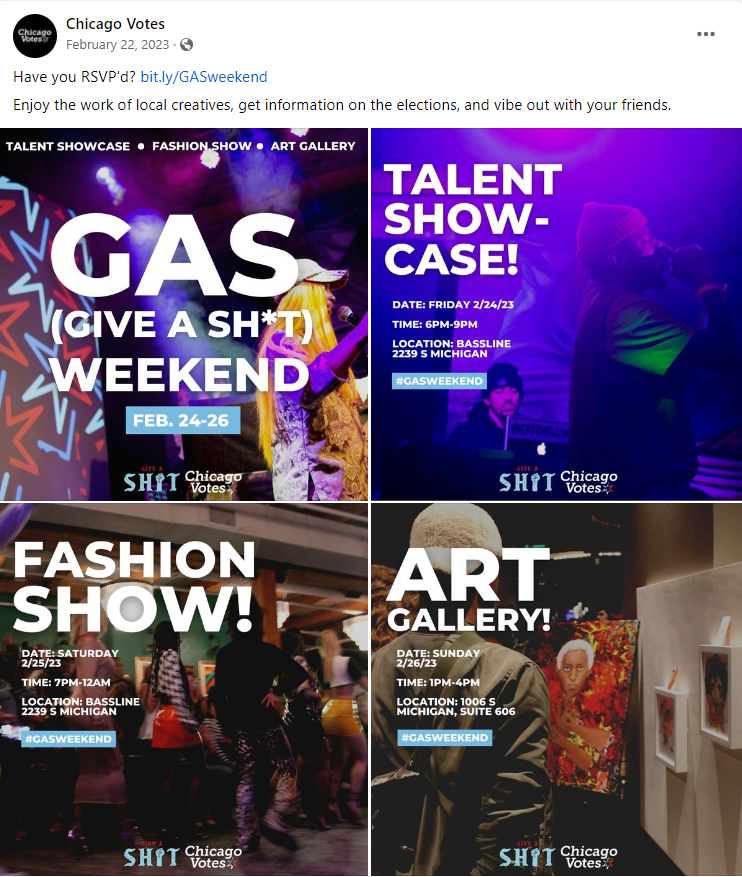

Corina often uses creative methods to engage youths in civic participation, such as hosting events at bars, organizing park gatherings and staging street festivals. “Otherwise, it becomes too serious and we lose them,” she said.

For her voter registration project with Chicago Votes, she organized a bar event with pop quizzes on political candidates and their policies. Participants also watched clips of the debate between candidates and rated their speeches using emojis.

“The goal is to spark casual conversations using creative ways, increasing their interest in learning more and registering to vote,” she added. On Election Night, she threw a party for youths who voted, featuring free drinks, live performances and a screening of the election results. “We wanted to make voting feel cool and exclusive, to positively reinforce the act,” she added.

Three principles have worked for Corina when engaging NEET youths to participate

Over the years, Corina has organized various dialogues for NEET youths to interact directly with government officials to share their stories and co-create solutions. She has identified three best practices:

- Research and personal engagement - she conducts research to understand NEET youth’s aspirations and challenges, so she can adopt a tailored approach when engaging them to participate. A teenage mother’s needs may differ from that of a young experiencing a disability so it helps to have social workers visit their homes, build relationships and gain deeper insights into their lives. “If they can’t come to us, we can go to them. This last-mile work is very resource intensive but it gives us key insights into what will encourage them to participate,” said Corina.

- Leveraging trusted figures - Second, she identifies trusted figures like religious leaders, social workers or teachers and works through them to invite NEET youths to participate. They usually know the youths personally, understand their challenges and can help to encourage participation. These trusted figures usually do not need much convincing because they are inclined to want the best for the youths.

- Youth-friendly spaces - she hosts events in accessible, comfortable environments like youth clubs, coffee shops and bars, especially those that are colorful or have beautiful decor, rather than locations like City Hall, which can be intimidating. “For NEET youths who are already hesitant to engage with decision makers, it is important that we create an experience where they feel comfortable to confidently express themselves,” said Corina.

For those who feel angry and inclined to protest on social media, Corina guides them to channel their anger constructively, such as through dialogues with decision makers, partnering researchers to generate data or running for office to be the alternative political opinion.

“I also tell them that one of the most important things is to come out to vote because almost every challenge they face is political - whether it's their ability to get a loan for a house or job opportunities. Things don’t change unless you put pressure on those in power,” she added.

Choose facilitators that youths can relate to

Corina has observed that migrant youths from the African continent may struggle to relate to facilitators from different racial or cultural backgrounds, such as a white, Eastern European woman like herself. To address this, she recommends involving facilitators who share similar racial or cultural backgrounds with the youths.

For example, when working with youths from Algeria, it helps to have a facilitator of Algerian descent or someone who speaks Arabic to lead the sessions. “Having facilitators that youths can relate to significantly enhances the quality of the discussion,” she said.

Maintain political neutrality

When organizing activities to encourage youths to vote, Corina ensures political neutrality by clearly stating that she does not represent any party. When organizing dialogues between candidates and young people, she makes sure to invite representatives from all contesting political parties and frame her questions in a neutral way that does not allow for any bias.

“Being neutral helps me persuade people who are on the fence to cast their vote. I remind them that voting is their chance to be heard and that change only comes if they vote,” she said.

Challenges

Youth civic engagement needs a more systemic approach

Despite her extensive efforts, Corina believes that legislation is essential for sustainable youth civic engagement. “It’s not enough for civil society workers and volunteers to rely on ad-hoc grant opportunities to organize civic engagement sessions.

We need laws that mandate national and local governments to engage citizens regularly; for example, making participatory skills mandatory in the curriculum of all schools,” she said.

Influencing funders to value the process as much as the outcomes

Funders often prefer projects addressing large-scale issues like unemployment or migrant integration but Corina argues that engagements focused on local issues deserve funding too.

“Some people may question the worth of citizens' engagement process for local issues but the value extends far beyond the issue because citizens are learning how to engage in a democracy,” she said.

She also encounters challenges in demonstrating the immediate value of civic engagement efforts, as results like policy changes or community projects may take months or even years to materialize and even then, it is difficult to attribute them to a particular engagement session.

“Funders need to understand that civic engagement requires a long-term commitment, yet there are few willing to invest in that way currently,” she said.