Lessons learnt from Participatory Budgeting in NYC

Read more about how the NYC Civic Engagement Commission used Participatory Budgeting to crowdsource meaningful ideas from New Yorkers to better use the city budget

Over seven years of co-founding and working with A Good Space, a cooperative of 34 changemakers, I developed a deep interest in citizen engagement and believe that ordinary citizens can be our best assets in addressing Singapore's complex challenges.

From August to November 2023, I worked at the Jacob A. Riis Neighborhood Settlement in New York City as part of the US Dept of State’s Community Solutions Fellowship. This transformative experience allowed me to observe Participatory Budgeting, a model that engages citizens to crowdsource and implements meaningful ideas for change.

In this article, I will share my observations, key lessons learned, comparisons to Singapore, and recommendations. All views expressed are solely my own and do not reflect the opinions of Riis Settlement.

Table of Contents

This is quite a long post (almost 4,156 words!) so I've added a Table of Contents to help you navigate around the post

- Quick context about New York City

- Two kinds of Participatory Budgeting in New York City

- About The People's Money

- Forming a coalition for Queensbridge - How I became involved

- Phase 1: Idea Generation

- Phase 2: Project development via the Borough Assembly Committee

- Phase 3: Voting

- Phase 4: Project implementation

- Personal reflections

- Comparisons to Singapore

- Suggestions

Quick context about New York City

Before jumping into the details, let's start with some context.

New York City (NYC) consists of five boroughs: Staten Island, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens and The Bronx, home to 8.4 million people. Each borough has council districts, totaling 51 districts, forming the city council that enacts legislation and passes budgets. The city also elects a Mayor who oversees various city agencies.

In 2018, voters created the New York Civic Engagement Commission (CEC) through a ballot. The CEC aims to restore civic trust and strengthen democracy by promoting inclusive civic participation for all New Yorkers.

They believe trust is built by engaging people's hearts and develop innovative programs to make civic participation more inviting, memorable and fun. Examples include: The People's Bus, a bus once used to transport detainees on Rikers Island that is now a mobile community center and The People's Money, the focus of this article.

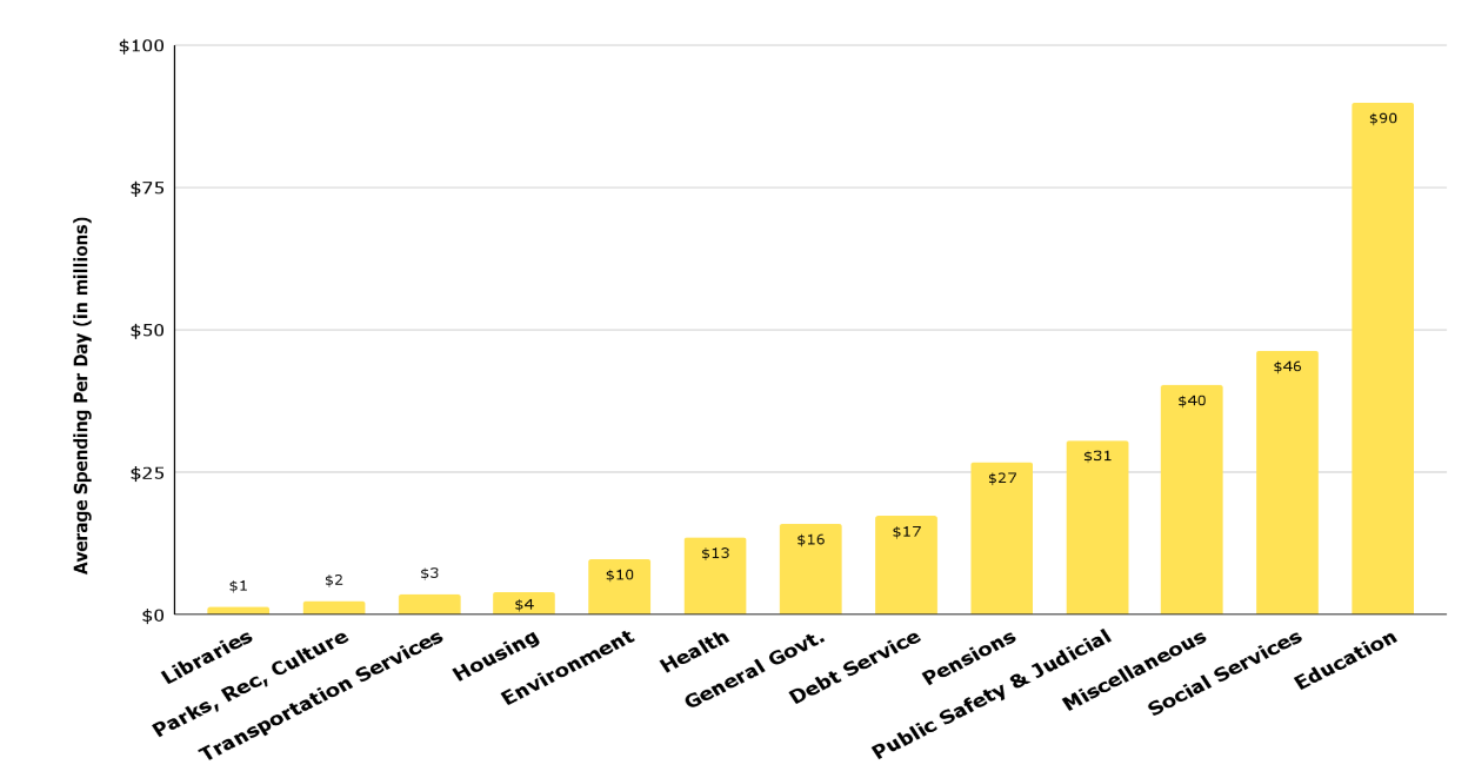

NYC spends $107 billion a year - more than many US cities and even some countries! On average, NYC spends $300 million per day, with the most going to education and social services.

To put that in perspective, Lebron James, one of the best basketball players in the world, has an estimated cumulative career earnings of $479.47 million over his 21-year playing career. NYC spends that in just over 1.5 days!

Two kinds of Participatory Budgeting in New York City

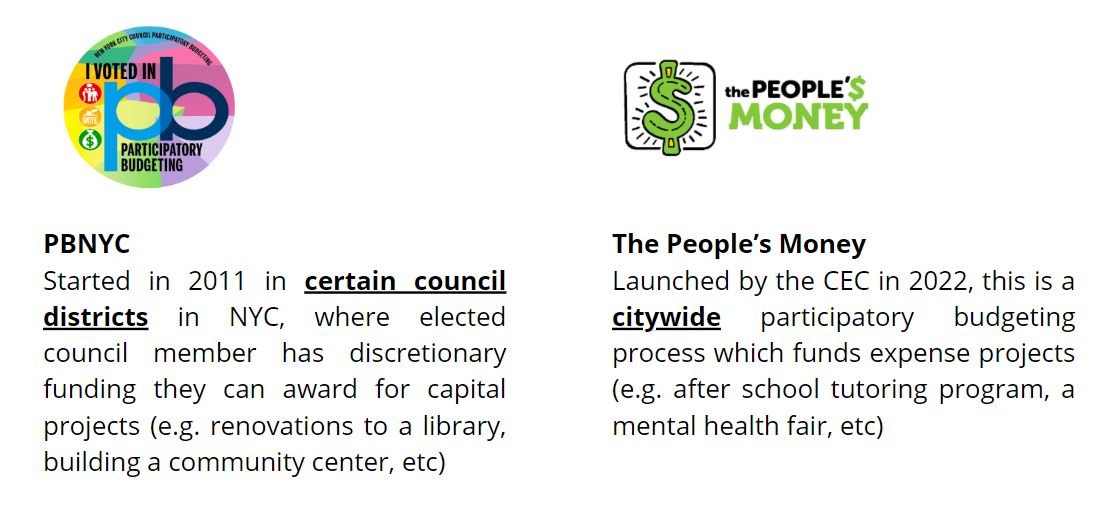

In 2022, NYC Mayor Eric Adams and the CEC launched The People's Money - NYC's first ever citywide Participatory Budgeting process. This initiative allows all New Yorkers aged 11 and above, regardless of immigration status, to decide how to spend $5 million of the city's budget to address local community needs.

Participatory Budgeting is a democratic process where community members can decide how to spend part of a public budget. It started in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 1989 and is credited with shifting priorities to support the poorest parts of the city. It has since been implemented over 11,000 times in cities all over the world.

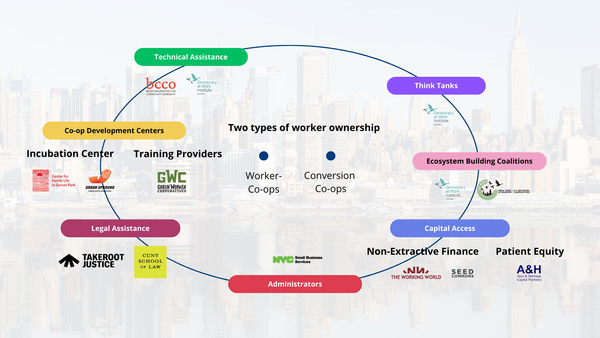

In NYC, participatory budgeting comes in two forms: Participatory Budgeting NYC (PBNYC) and The People's Money. PBNYC focuses on capital projects within specific districts such as library renovations, while The People's Money is a citywide process open to all New Yorkers aged 11 and above, supporting expense projects such as programs, services and events.

About The People's Money

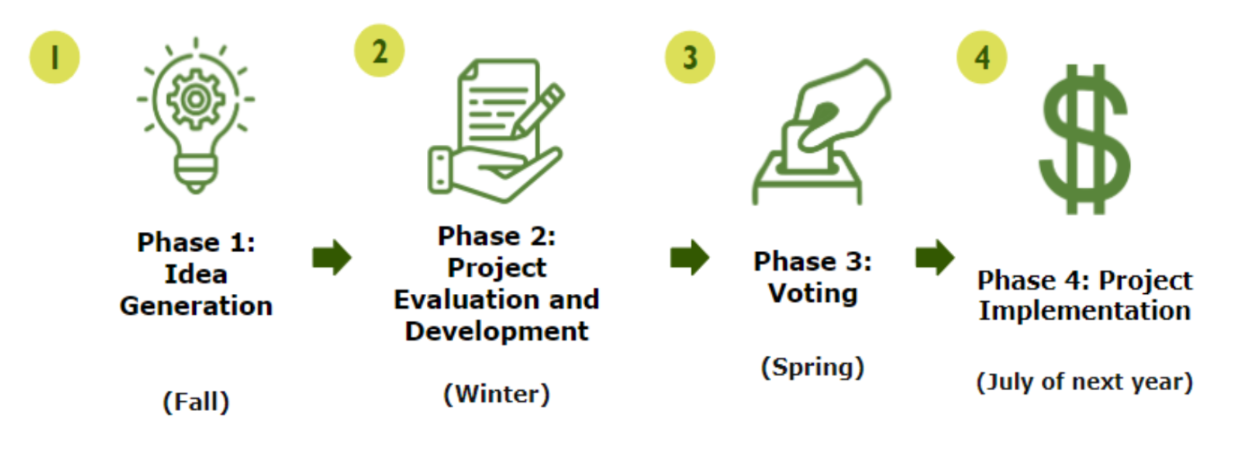

There are four phases to The People's Money in NYC:

- Idea generation - New Yorkers participate in workshops to learn about the city budget cycle, identify community needs and brainstorm ideas for expense projects. Ideas can also be submitted online.

- Project evaluation - The CEC and Borough Assembly Committees refine and select the best ideas to move onto the ballot in Phase 3.

- Voting - Residents vote on the ideas, either online or in-person, in multiple languages at sites across the five boroughs.

- Project implementation - winning ideas receive city funding for implementation. The CEC puts out a call for implementation partners and selects the best proposal. Anyone can apply.

Forming a coalition for Queensbridge - how I became involved

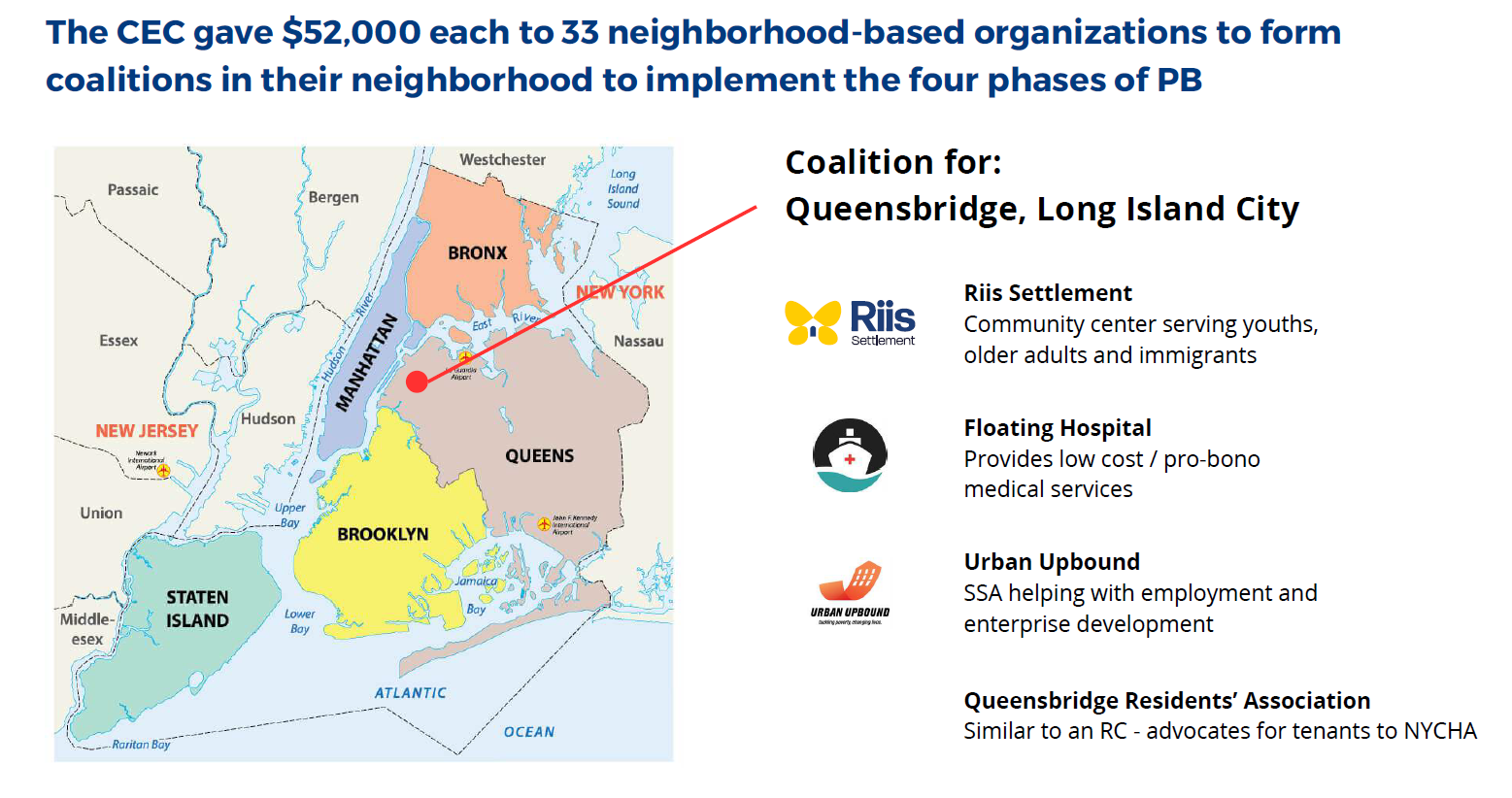

To roll out Participatory Budgeting across NYC, the CEC issued a grant call for organizations to form coalitions with at least three other organizations in their neighborhood.

I helped to write a successful application for Riis Settlement, securing US $52,000 to be the Coalition Lead for Queensbridge. Our coalition included the Floating Hospital, a non-profit clinic providing low cost / pro bono medical services, Urban Upbound, a social service agency with employment and enterprise development programs for low-income persons and the Queensbridge Residents' Association, a volunteer group advocating for public rental tenants in Queensbridge, similar to Singapore's Residents' Committees.

Phase 1: Idea Generation

In Phase 1, we organized five 2-hour idea generation workshops for 20 - 25 residents of Queensbridge (Queens, NY 11101) to brainstorm ideas. Participants were divided into teams of 5, each with a leader and note-taker, and engaged in a structured game.

Round 1: Pick one type of city (10 mins)

Teams choose one of five "Great City" cards containing a different aspiration for Queens (e.g. public safety, eco-friendliness, etc) to guide their brainstorming.

Round 2a: Pick one type of resident (15 mins)

Teams selected one of nine "Resident" cards, each containing a different type of resident that might live in NYC. Teams who didn't like any of the cards could create their own resident profile.

Round 2b: List down challenges that this resident faces (5 mins)

Team members each listed two challenges faced by their chosen resident, with the note-taker keeping track of what was mentioned. For example, teams who chose Dimitri, an 11 year old boy who lives with his single mom in public housing listed challenges such as:

- Food insecurity

- Language barriers when trying to connect to social services

- Challenges for his mother in accessing work because she is a single mom

Round 2c: List down strengths that this resident has (5 mins)

Team members also listed two strengths of their chosen resident. For example, Dimitri's mother was noted for her resilience and resourcefulness to care for her son alone, and Dimitri for being well-manner and diligent in keeping up with his schoolwork.

This segment was added into the design to foster a strengths-based approach, beyond seeing people as just their problems.

Round 2d: Clarify resident chosen

The note-taker summarized the chosen resident, their challenges and strengths for the team so it could have a clear resident they were trying to generate ideas for later.

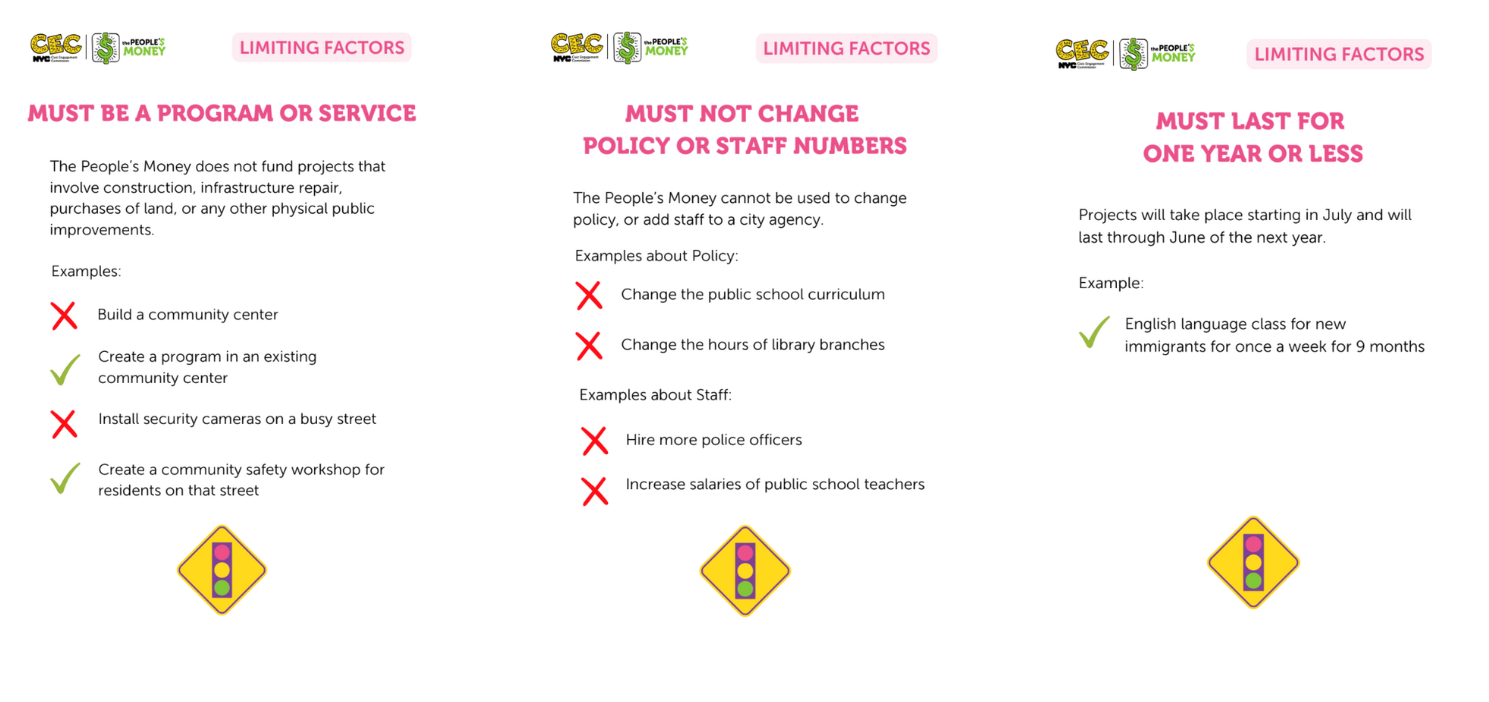

Round 3: Read and understand the limiting factor cards (5 mins)

Teams reviewed six "Limiting Factor" cards to ensure their ideas fit within the CEC's guidelines. For example, one constraint was that the idea generated must be either a program or service and not something that will lead to the construction of infrastructure. This helped to increase the likelihood of meaningful ideas being generated.

Round 4a: Pick one brainstorming method (5 mins)

Teams selected one of four brainstorming methods, such as scanning a QR code to read about past projects to find inspiration that might relate to their chosen resident.

Personally, I thought this last round might be unnecessary, although still a good to have. I noticed that by the time the constraints were discussed, participants were raring to go and didn't need much support in choosing a brainstorming method.

Round 4b: Brainstorm individually in silence (5 mins)

Participants individually wrote down two ideas on post-its notes in silence. We invited participants to consider the following when brainstorming:

- Try to think about what has not been tried before

- It's not about debating whose idea is best, listen to each idea expressed

- The idea has to improve the life of the chosen resident, towards the vision of the Great City that their group chose

Round 4c: Shareback in small group and decide on one idea (10 mins)

Participants shared their ideas, and the leader facilitated a conversation to come to consensus on one idea to submit to the CEC.

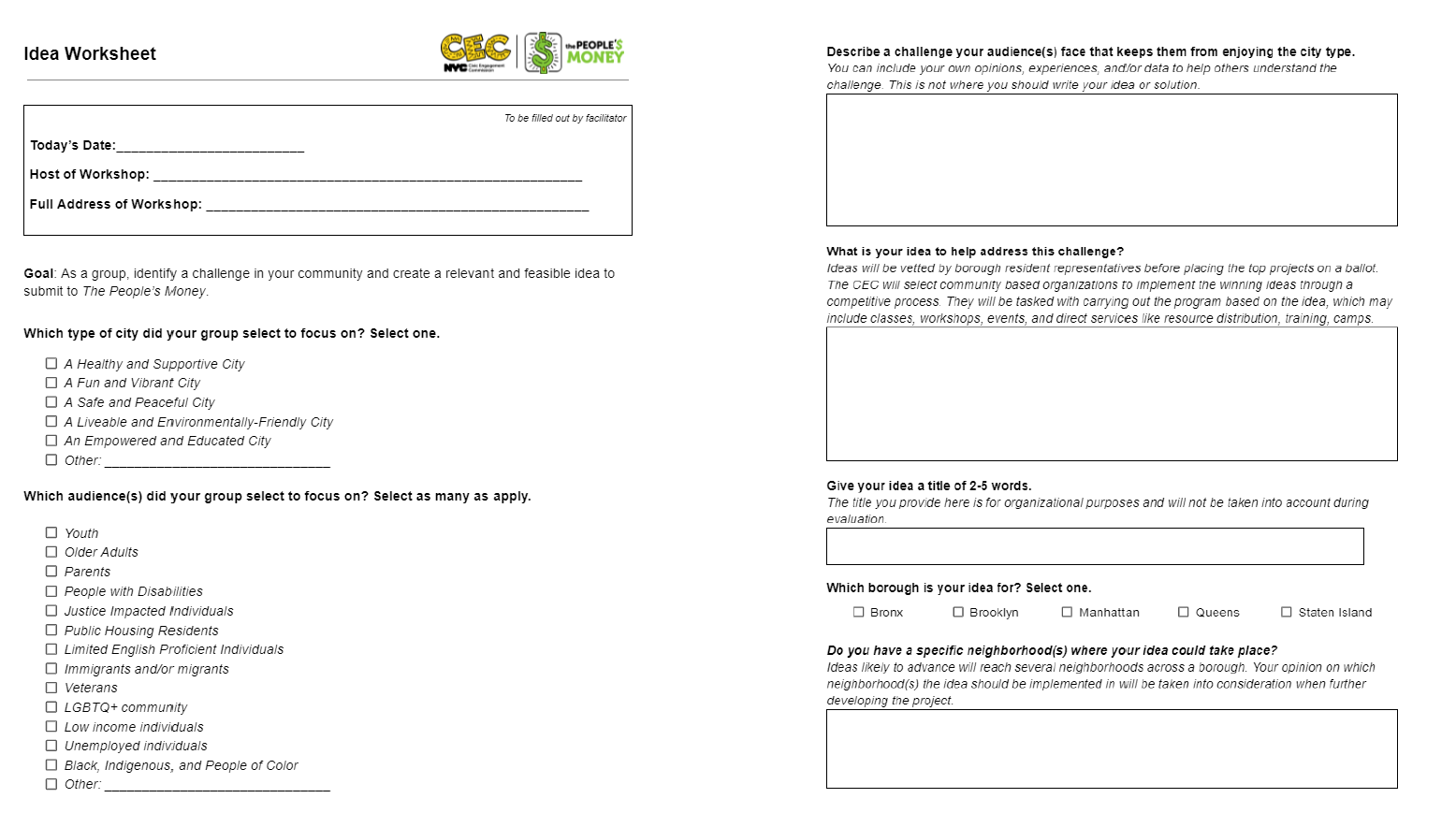

Once this idea was decided, the note-taker had to complete an Ideas Worksheet, giving as many details of the idea they agreed upon as possible. Participants completed a post-workshop survey and could indicate their interest to serve on the Borough Assembly Committee (see below).

Video showing some meetings of the Queens Borough Assembly Committee, video credit: NYC CEC

Phase 2: Project Development via the Borough Assembly Committee (BAC)

5 Borough Assembly Committees (1 for each borough in New York City) comprising 20 - 25 residents matching the demographics of the borough will narrow down all the ideas generated from Phase 1 and get to 10 ideas that will go on the ballot in Phase 3. The process is as follows:

Step 1: CEC disqualifies ideas that don't fit the criteria

The CEC reviews all ideas submitted from the Idea Generation workshops in Phase 1 or online, disqualifying those that:

- Are capital projects (i.e. construction of infrastructure)

- Increase government agency headcount

- Are policy recommendations

- Are incoherent or intolerant of others

- Lack sufficient details or clarity

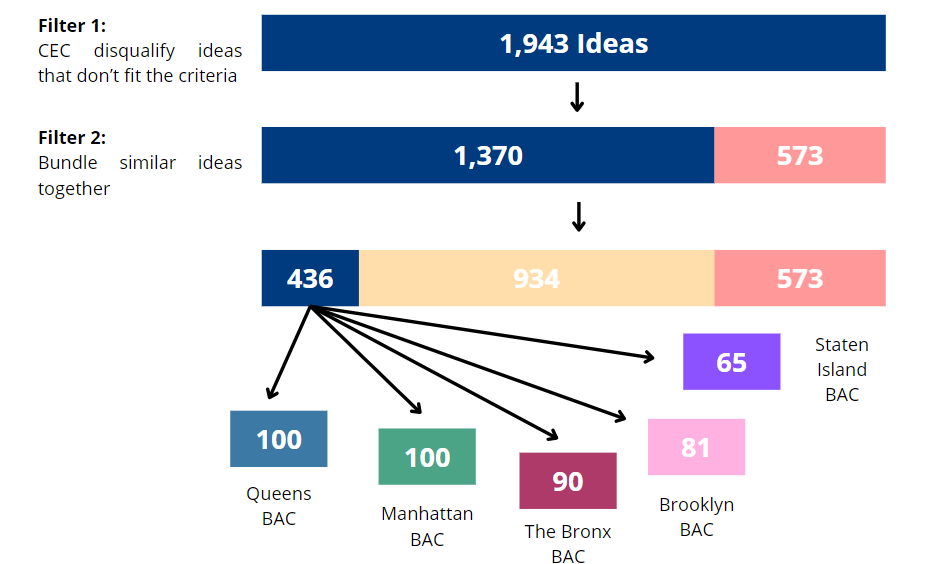

In the 2023 - 2024 run of The People's Money, 573 out of the 1,943 ideas collected were disqualified by the CEC.

Step 2: CEC bundles similar ideas together

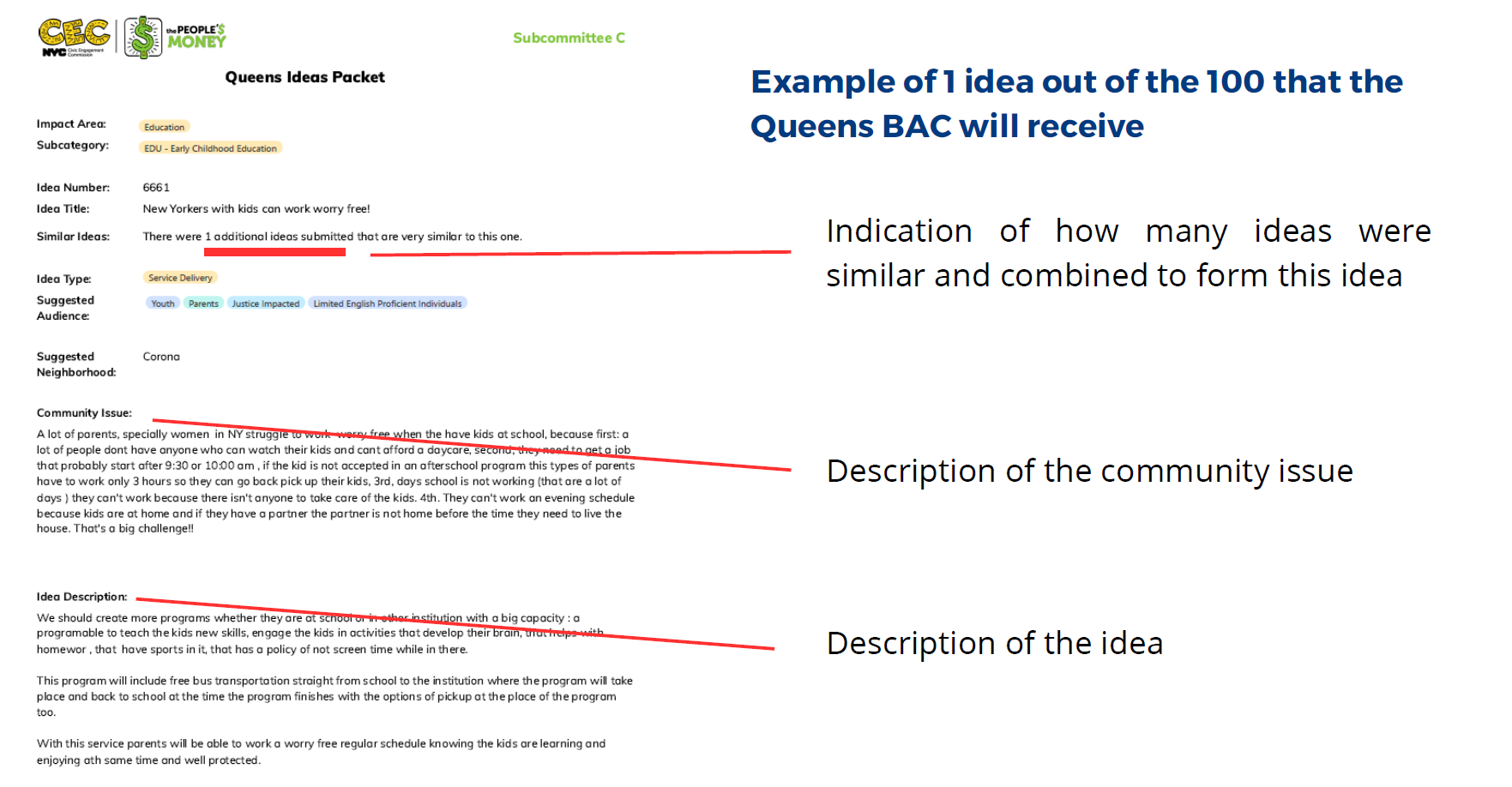

The CEC then combines similar ideas into single entries. For this cycle, 934 ideas were merged, leaving 436 unique ideas. These consolidated ideas are organized by borough and presented to the BACs in their first meeting (see Step 3 below). Larger boroughs like Queens typically receive more ideas than smaller boroughs like Staten Island.

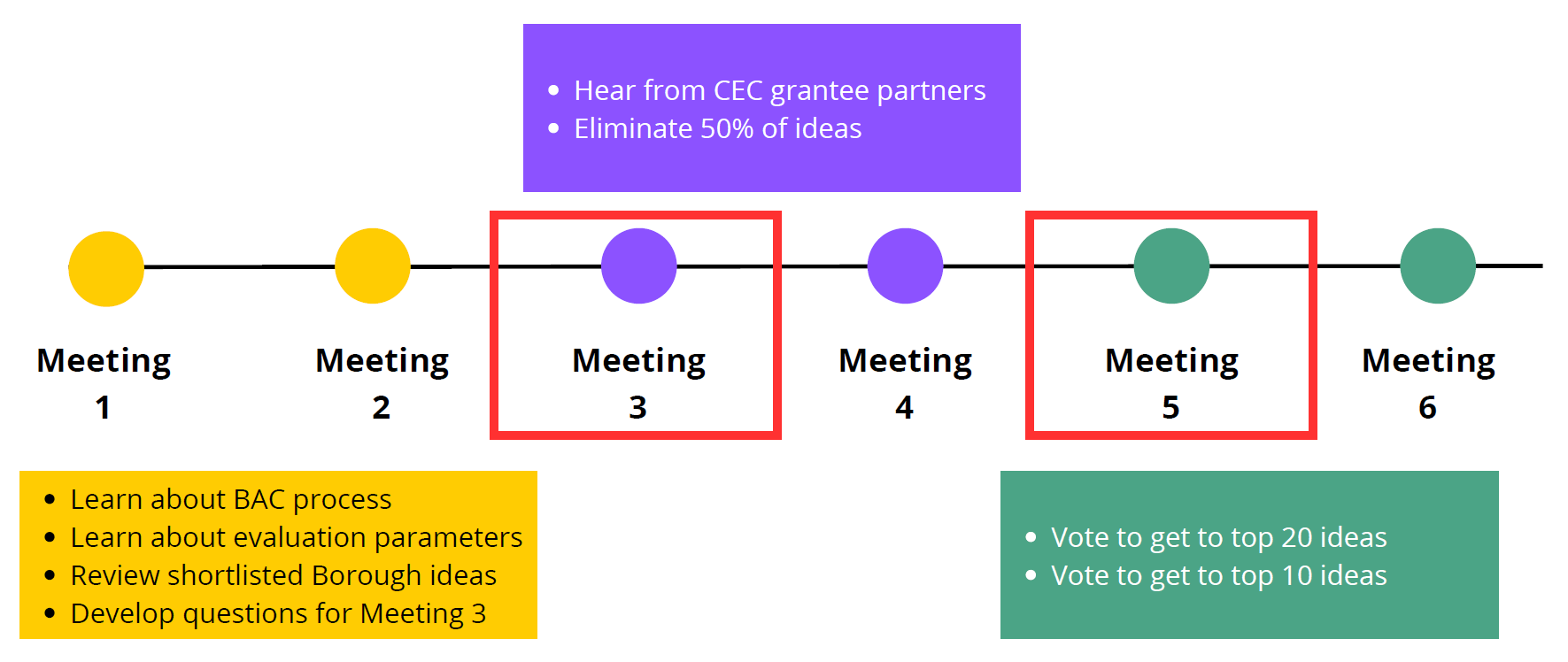

Step 3: BAC narrows down ideas over 6 meetings

Over six meetings, each BAC discusses and refines the ideas for their borough (e.g. 100 ideas for Queens) to 10 that will go onto the ballot in Phase 3.

The process starts with Meeting 1 and 2, where participants learn about the BAC process, evaluation criteria and prepare questions for the Coalition Leads.

In Meeting 3, Coalition Leads such as Riis Settlement, help provide insights on community needs and existing services to help BAC members who may not be familiar with issues on the ground (e.g. childcare for children with special needs), to make informed decisions.

Later on in Meeting 5, the Coalition Leads return to offer final input as the BAC votes to narrow down the ideas to 20 and eventually the final 10 that will appear on the ballot in Meeting 6.

Video showing the CEC going to the Staten Island Family Fun Day 2024 to encourage residents to vote on the ideas for Staten Island, video credit: NYC CEC

Phase 3: Voting!

Residents aged 11 and above, regardless of immigration status, can vote on their borough's ballot either in-person or online, for projects they want to see funded. (i.e. a Queens resident could only vote on ideas for Queens)

How the CEC got votes in

The CEC aimed to increase ballots cast to 150,000 this year, up from the 100,000 last year. They did this by participating in major community events (e.g. the Staten Island Family Fun Day mentioned in the video above), organizing their own events and investing in social media and out-of-home advertisements.

They also required each Coalition Lead to collect 2,000 votes. At Riis Settlement, my colleague Eric Duncan used a variety of strategies to collect 1,522 in-person and online ballots, including:

- Asking students of our English for Speakers of Other Language (ESOL) classes who were mostly new immigrants to New York City

- Setting up a booth at the neighborhood library on weekends where foot traffic was high

- Going to Middle Schools where we ran after-school programs to encourage students there to vote

- Working with our coalition partners to place ballot boxes in their offices and getting them to share social media posts encouraging their community members to vote

- Paying a stipend to 5 youth ambassadors from high schools around the area to get their schoolmates to vote

Phase 4: Project Implementation

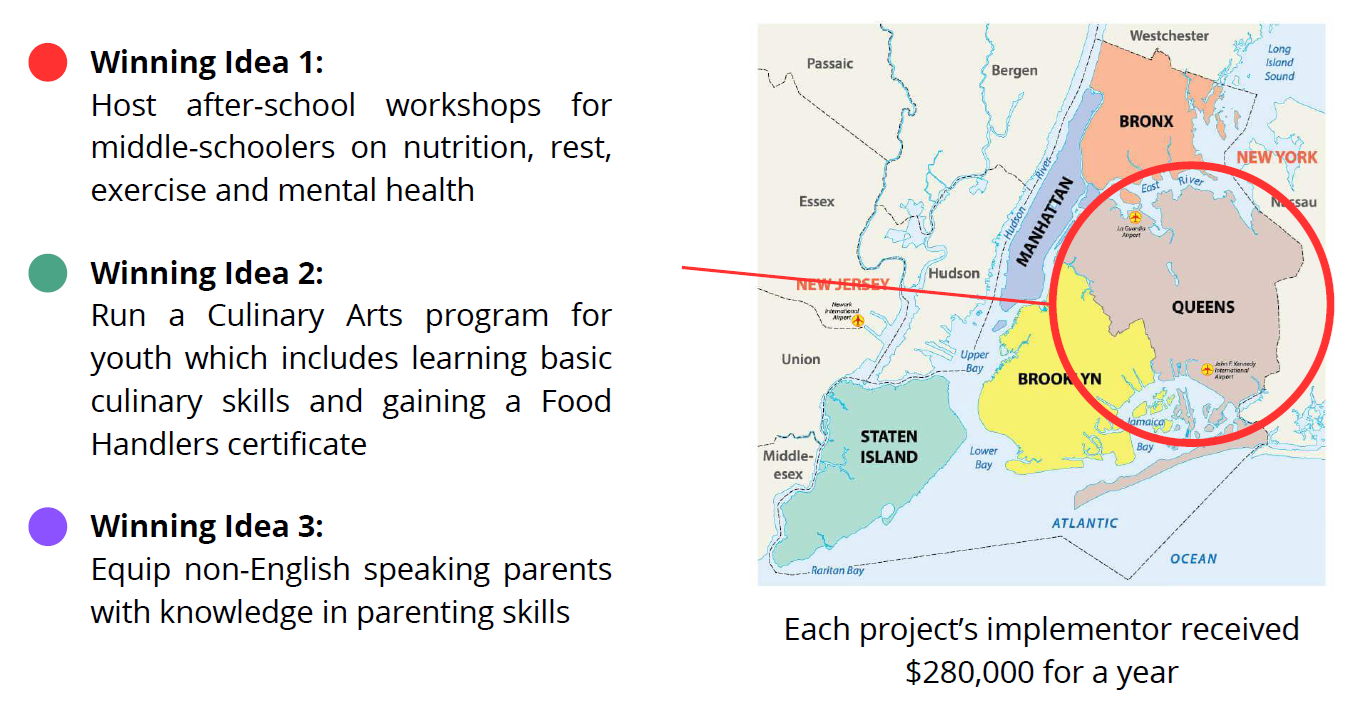

At the time of writing, the projects selected for Phase 3 have yet to be announced. However, based on the 2022 - 2023 cycle, the top ideas (out of the 10 on each borough's ballot) are chosen for implementation.

The CEC then issues a Request for Proposals (RFP) for individuals or organizations interested in receiving funding to implement the selected ideas. For example, here are some of last year's winning ideas for the Queens borough:

After selecting an implementer, project implementation takes place over a year, with the chosen partner required to meet specific milestones along the way.

Personal Reflections

In addition to the process described above, I observed several interesting things which gave pause for reflection:

The CEC's partnership with Coalition Leads

Immediately after being awarded the grant as the Coalition Lead for Queensbridge, we attended a training session with the CEC. Dr Sarah Sayeed, the Director, addressed all 33 Coalition Leads, affirming our value and outlining the spirit of partnership that the CEC would engage us in, saying something like:

We honor the deep relationships, trust and good work you have done in your communities over the years and we will not be able to do Participatory Budgeting without you. We want this to go beyond a transactional grantor-grantee relationship to nurture a learning partnership, where the CEC can learn from your successes and help provide resources to strengthen your ability to mobilize communities.

Wow.

As someone who has tried to do citizen engagement work in Singapore and faced various challenges, I was heartened by their recognition of the value of community organizers and their desire to help organizers build skills to mobilize better. The humility and sincerity in Dr Sayeed's message was particularly moving.

Beyond providing the US $52,000 funding, the CEC supported each Coalition Lead by:

- Providing training and materials to build skills for facilitating the Idea Generation workshops

- Assigning a Relationship Manager for each borough, serving as a liaison for support if they were facing any challenges meeting their deliverables

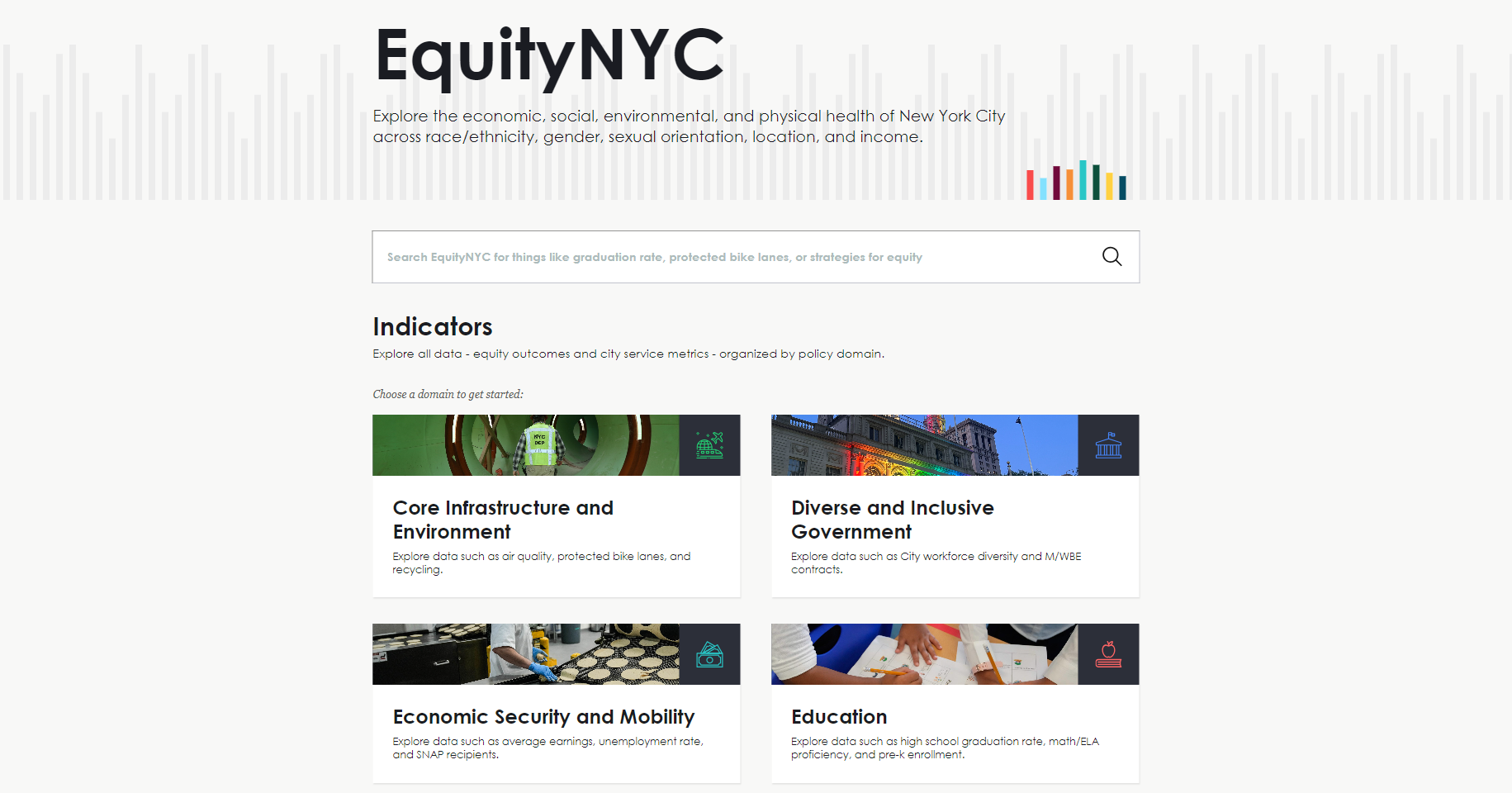

- Hosting monthly meetings with representatives from other city agencies to share tools and skills useful for Coalition Leads, such as EquityNYC

Notably, the CEC could have opted to engage five sub-contractors (one for each borough) to run the Participatory Budgeting process. This might have been easier and more resource-effective than managing 33 Coalition Leads.

This choice to engage deeply with community organizers speaks volumes and offers a contrast to practices observed in Singapore. More on this in the comparisons section below.

3 drawbacks of the Participatory Budgeting model

Despite its benefits in promoting inclusive citizen participation, I observed three potential drawbacks of this model:

- Not enough scaffolding in Phase 1 - The idea generation workshop was too short. While citizens may be experts of their lived experiences, it is difficult for them to generate meaningful ideas on the spot without some support, such as being shown inspiring ideas tried in other countries for similar issues.

- Citizens might feel disappointed - Some citizens may feel strongly about an idea in Phase 1 that doesn't make it to Phase 4 after inputs from the BAC in Phase 2 and voters in Phase 3. Additionally, the person who suggested the idea in Phase 1 might not be awarded the proposal to implement it, leading to potential disappointment.

- Mechanism for idea sustainability is unclear - for projects chosen for implementation, it is unclear what happens after the year of funding ends and what support the CEC can provide to help ideas continue.

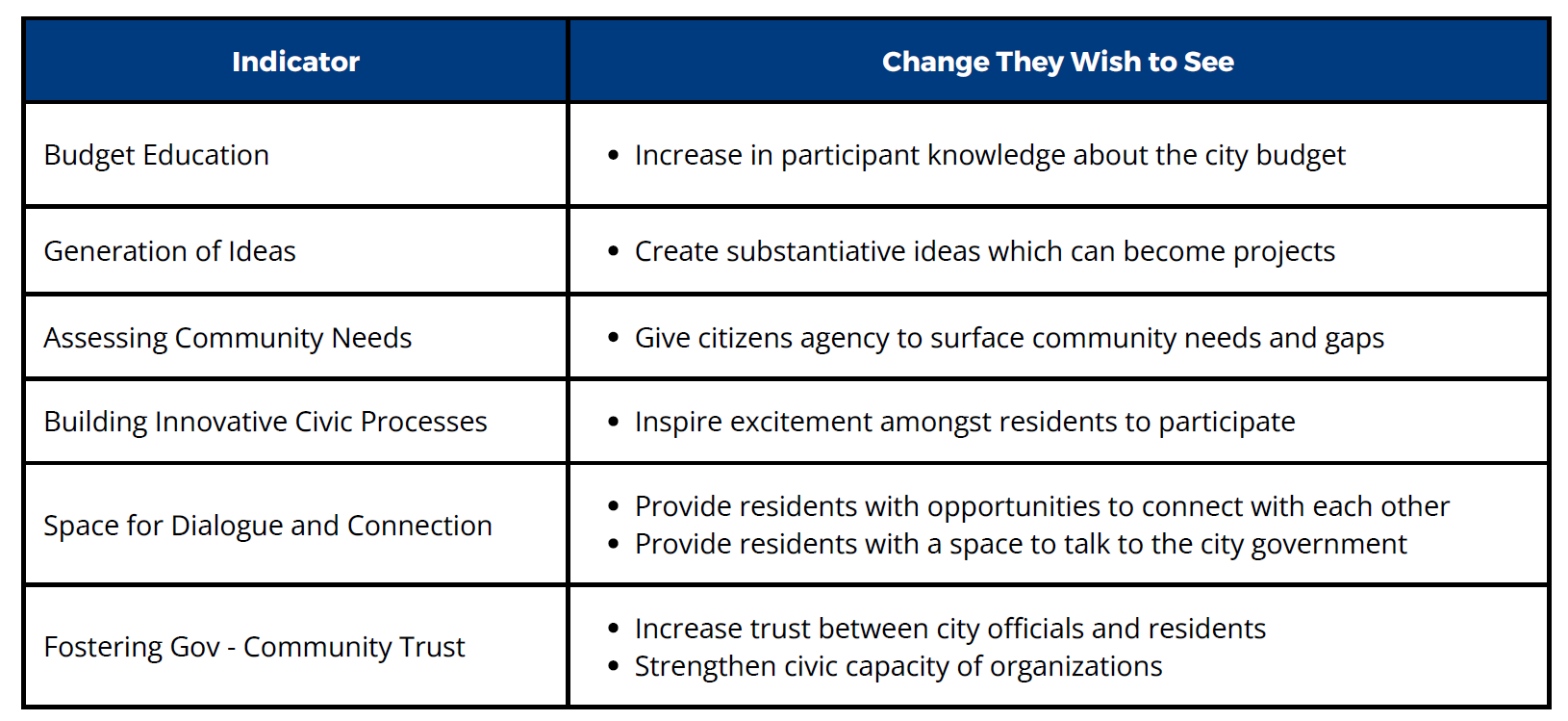

How the CEC evaluated their impact in Phase 1

It was interesting to observe how the CEC evaluated the success of the Idea Generation workshops in Phase 1 using six indicators, collected through exit surveys and partner feedback reports.

Comparisons to Singapore

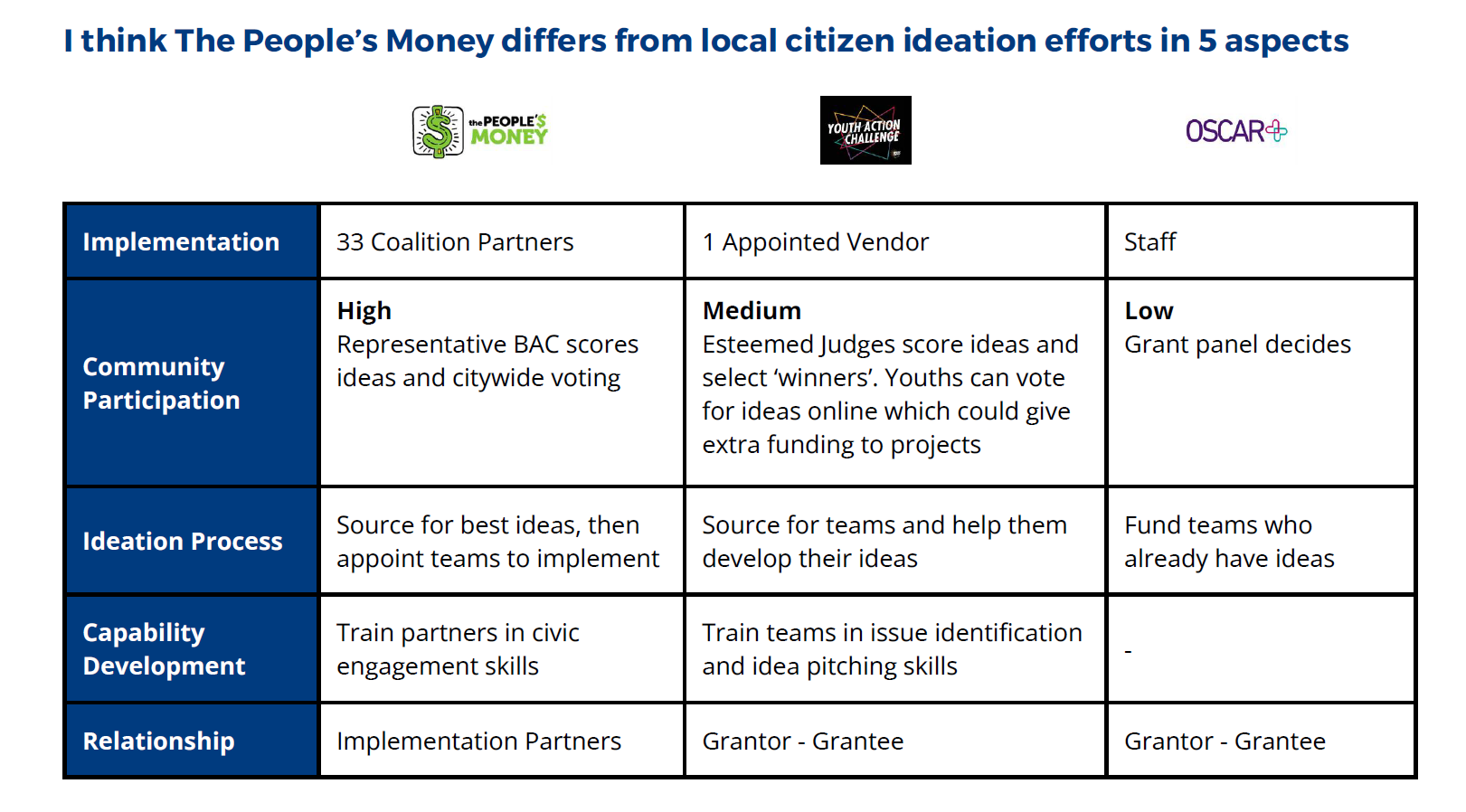

How does The People's Money compare to efforts in Singapore? Based on my understanding, I have compared it to two efforts with similar objectives of encouraging citizen participation:

- The National Youth Council's Youth Action Challenge (YAC) - an annual 4-month program where teams of youths ideate, pitch and receive funding for solutions that drive meaningful change. The YAC also has a Participatory Grantmaking element, allowing other youths to allocate a virtual budget of $30,000 to their favourite teams.

- The Temasek Foundation's OSCAR Fund - a grant up to $50,000 to support ground-up initiatives by citizens and residents. Similar grants in Singapore include The Majurity Trust's SG Strong Fund and the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth's Our Singapore Fund.

Comparisons are made across five dimensions, which uncover some potential recommendations mentioned in the final section of this article.

Implementation

The first difference is in how the process was implemented. The CEC enlisted 33 Coalition Leads to implement the Participatory Budgeting process in different neighborhoods across New York City through a grant call. This approach yielded two benefits:

- Skills development - It allowed the CEC to train Coalition Leads in civic engagement skills, enhancing their community organizing capabilities.

- Leverage on community trust - It enabled the CEC to leverage the high trust the Coalition Leads have built over the years to engage communities that might otherwise distrust civic participation, such as ex-offenders, low-income single mothers or immigrants, making the process truly inclusive. The CEC, or any single vendor they engaged, would not have been able to achieve this alone.

In contrast, the YAC typically engages a primary vendor, such as 500 Startups or Empact, to implement its 4-month program, who then sub-contracts parts of the work to smaller vendors. Funds like OSCAR fund have in-house staff to sift through grant applications received before presenting them to a grant panel for final decisions.

A video showing the Youth Action Challenge process, video credit: National Youth Council, Singapore

Community Participation

The level of community participation in deciding which ideas to prioritize differs significantly between models.

The level of community participation in The People's Money is very high, citizens generate ideas in Phase 1, and a BAC that is representative of the demographics in the borough gets to filter through the ideas, which are voted on in Phase 3 by the citizens. By the time the idea gets to Phase 4, many citizens have had a hand in shaping it - it is not clear who the idea 'belongs' to.

The level of community participation in the YAC is also relatively high, as youths get to form teams to develop their ideas and even get to vote for ideas they like to receive extra funding. However, the final selection is made by a panel of judges, slightly reducing the level of community participation compared to The People's Money.

Funds like OSCAR are quite traditional in that a grant panel of distinguished persons reviews submitted ideas and makes funding decisions. Community input in shaping the ideas is relatively low.

Ideation Process

The People's Money sources for the best ideas from citizen input and then appoints teams to implement these ideas. The YAC sources for teams and helps them to develop their ideas to be pitch-worthy and receive funding. Whereas funds like OSCAR support teams that already have developed ideas.

Capability Development

The People's Money sought to train Coalition Leads in civic engagement skills, whereas YAC sought to train teams in issue identification and pitching skills. Funds like OSCAR typically do not offer capability development training.

Relationship with partners

The People's Money engaged with the Coalition Leads as implementation partners on an equal footing whereas the YAC and funds like OSCAR may engage with participants through a grantor-grantee relationship.

Suggestions

In closing, reflecting on the Participatory Budgeting experience, here are two suggestions for improving citizen engagement processes in Singapore:

- What if we had a BAC for evaluating ideas? - could we introduce more citizen participation on grant panels that evaluate ideas submitted by citizens, beyond the esteemed professionals that typically serve on such panels? For example, could we include a low-income mother to judge an idea for low-income families?

- Could we give community-based organizations more opportunities to shape civic engagement in Singapore? - what if we funded multiple community-based organizations to run the Youth Action Challenge or the Forward Singapore Conversations that happened in 2023?

For example, imagine a Youth Action Challenge organized by organizations which enjoy high trust in specific neighborhoods such as Beyond Social Services (Jalan Klinik), South Central Community Family Service Centre (Delta Road), Allkin Limited (Ang Mo Kio) and the Tzu Chi Humanistic Youth Centre (Yishun).

Would this lead to more inclusive participation and help alleviate some of the problem that the National Youth Council constantly faces in attracting youths from lower socioeconomic backgrounds?

Involving more organizations in community organizing work beyond the usual agencies like the People's Association could lead to the strengthening of Singapore's social fabric and resilience. Embracing the inherent messiness of involving multiple players might lead to a richer, more engaged community.