Lessons learnt from worker co-ops in New York City

Worker co-ops can lead to increased wages, wealth and more resilient businesses. Here's how New York City is encouraging worker co-ops.

From August to November 2023, I worked at a 130-year old nonprofit in New York City through the US Department of State's Community Solutions Fellowship.

On my off days and during the weekends, I tried to connect with people working in the worker co-op space in New York City, to learn how they were cultivating worker ownership.

I wasn't making much headway until my last month, when I connected with Raybblin Vargas from Green Worker Cooperatives, who invited me to the Democracy at Work Institute's (DAWI) 10 year anniversary celebration one evening in Brooklyn.

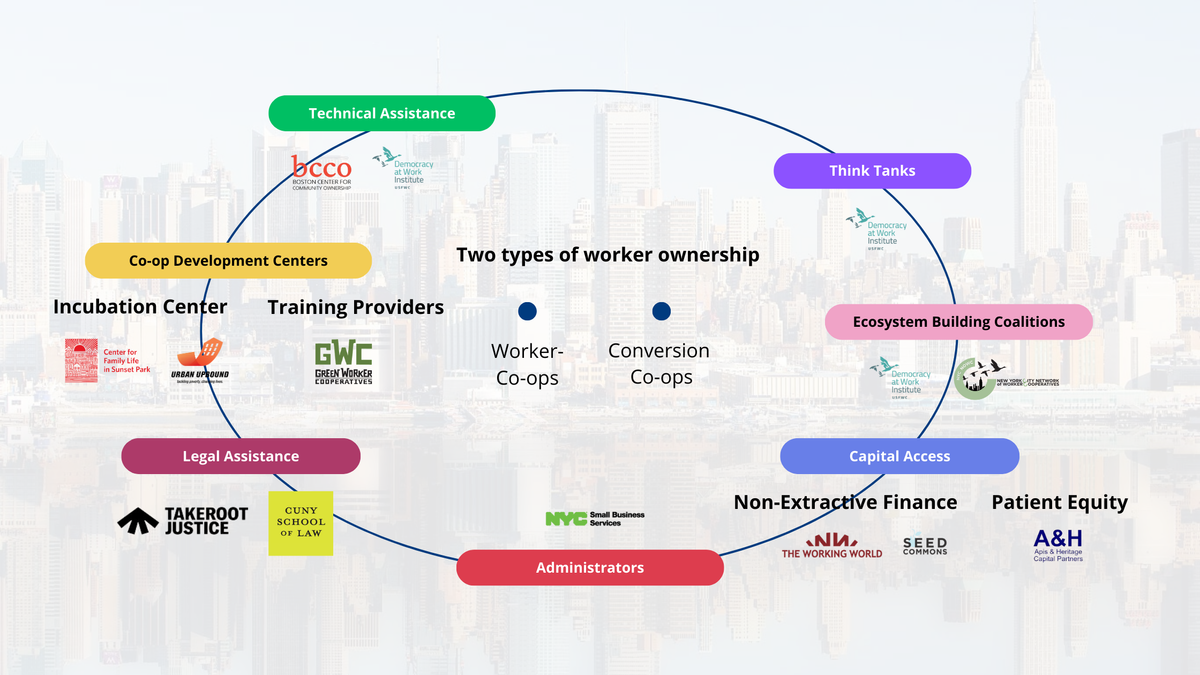

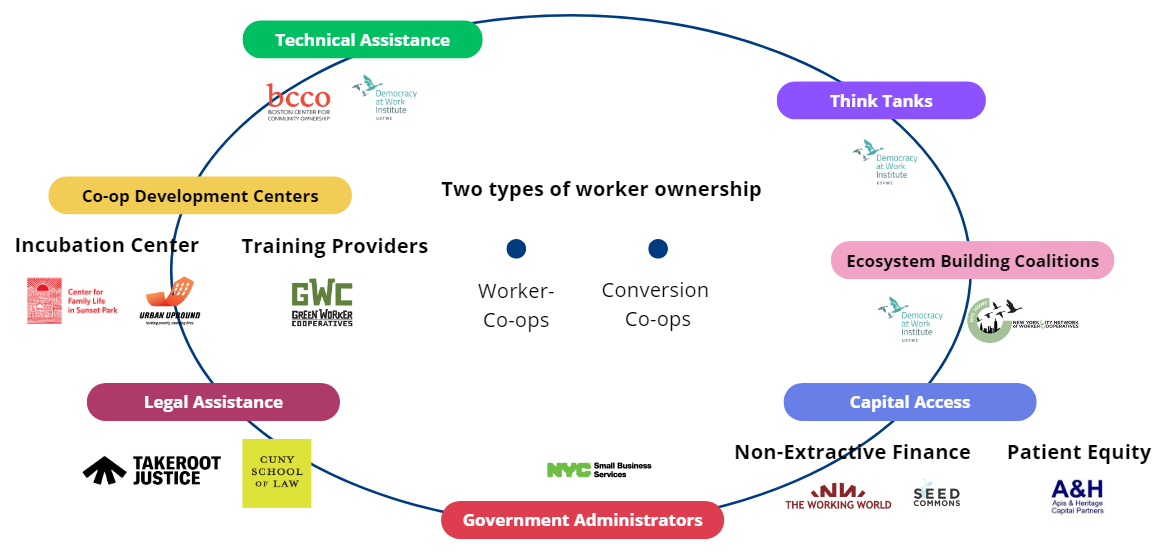

At the event, I connected with various stakeholders in the worker co-op ecosystem, including: co-op incubators, legal assistance providers, patient equity forms and technical assistance providers.

I was struck by the diversity of stakeholders supporting co-ops in the United States, compared to Singapore where we only have two - the Registry of Cooperative Societies (RCS) and the Singapore National Cooperative Federation (SNCF).

These connections at the event led to valuable one-on-one meetings, which were a significant breakthrough, providing me with deeper insights and learnings.

Everything mentioned in this article is only possible because of these people and Raybblin. I am deeply grateful to them and in particular Raybblin, for her generosity in sharing her experience, networks and ideas.

Table of Contents

Even though I've tried to fit in only the most important lessons learnt and reflections, this still ended up being a very long article so here is a Table of Contents to help you navigate quickly around it:

- Three key issues driving worker ownership in the US

- Two kinds of worker ownership

- Worker co-op ecosystem in New York City

- Cooperative Development Centres

- Technical Assistance Providers

- Capital Access Providers

- Think Tanks

- Legal Assistance

- Administrators

- Ecosystem Building Coalitions

- Key reflections from New York City

- Recommendations for Singapore

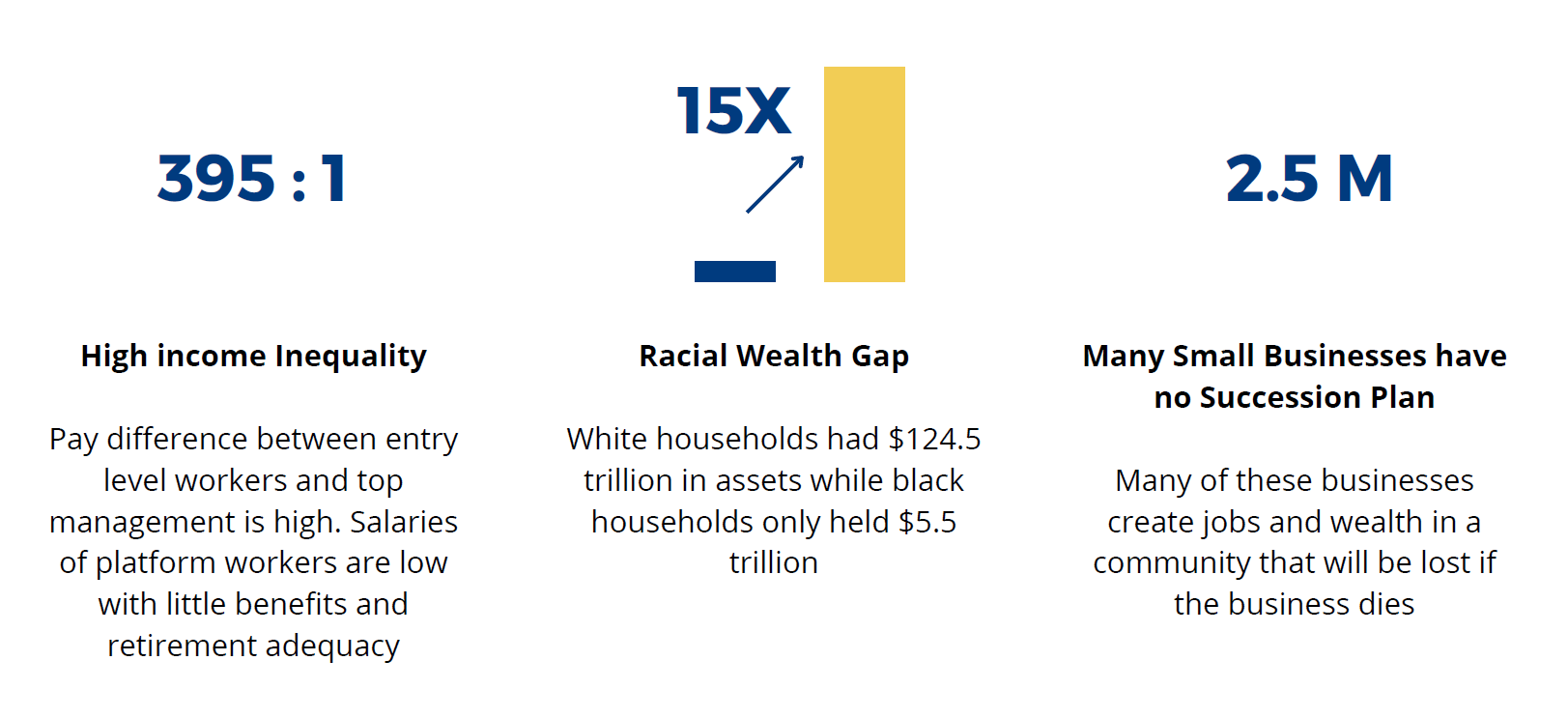

Three key issues driving worker ownership in the US

At the event, I learned that worker co-ops are being formed across the United States because they can address issues like income inequality, the racial wealth gap, and the lack of small business succession plans.

Two kinds of worker ownership

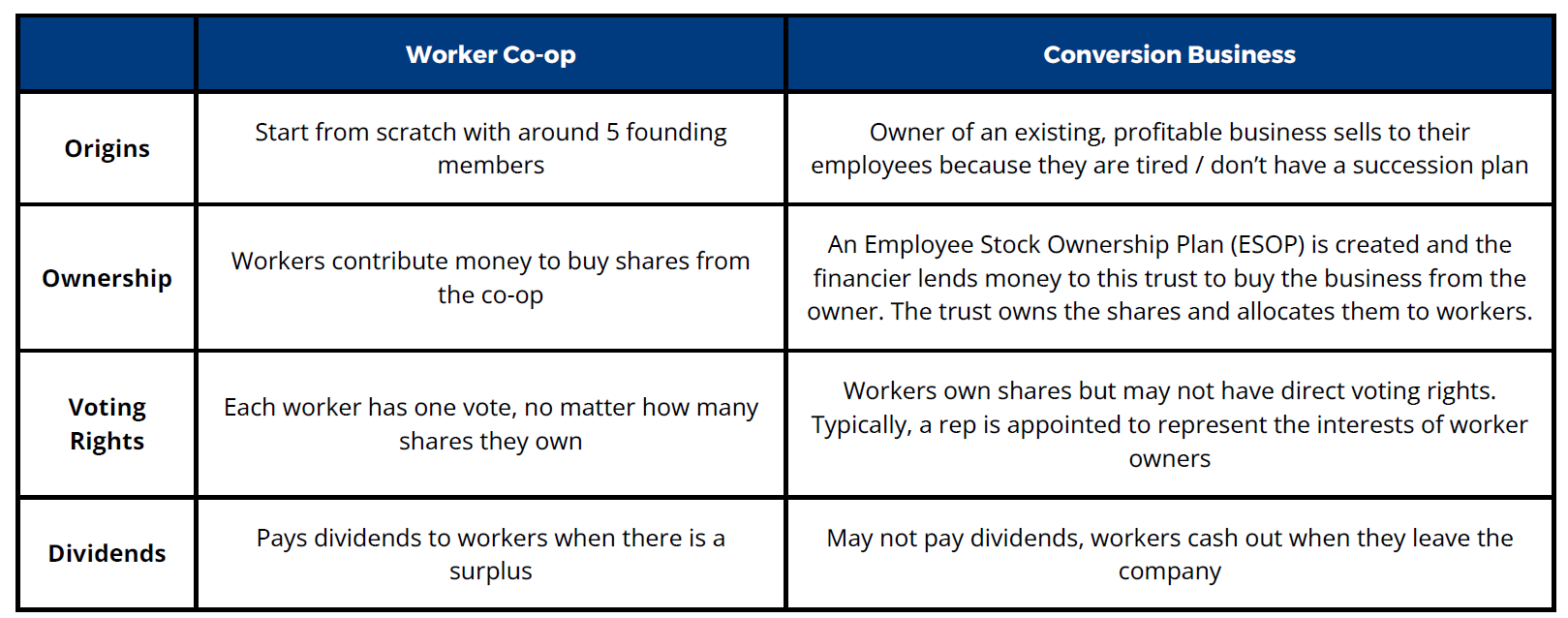

Worker ownership can happen in two ways: (i) a group of people coming together to start a worker co-op from scratch or (ii) converting a profitable business into being worker-owned.

Worker Co-ops

These are new businesses started from scratch by a group of around 5 founding worker-owners. The founding members may contribute personal funds or secure loans from non-extractive lenders like Seed Commons (see below) to raise the capital needed to start the business.

Each worker-owner holds one vote for decision-making, regardless of the number of shares they own (i.e. the "one member, one vote" principle of cooperatives). This contrasts with a public-listed company, where larger shareholders typically have more influence over decision making.

Conversion Businesses

These involve converting an existing profitable business into a worker-owned co-op. This often occurs when a business owner either lacks a succession plan or is too tired to continue.

Financing could come from either a non-extractive lender such as the Baltimore Roundtable for Economic Democracy ,a patient equity firm such as Apis & Heritage Capital Partners or traditional bank loans.

Some examples of this include:

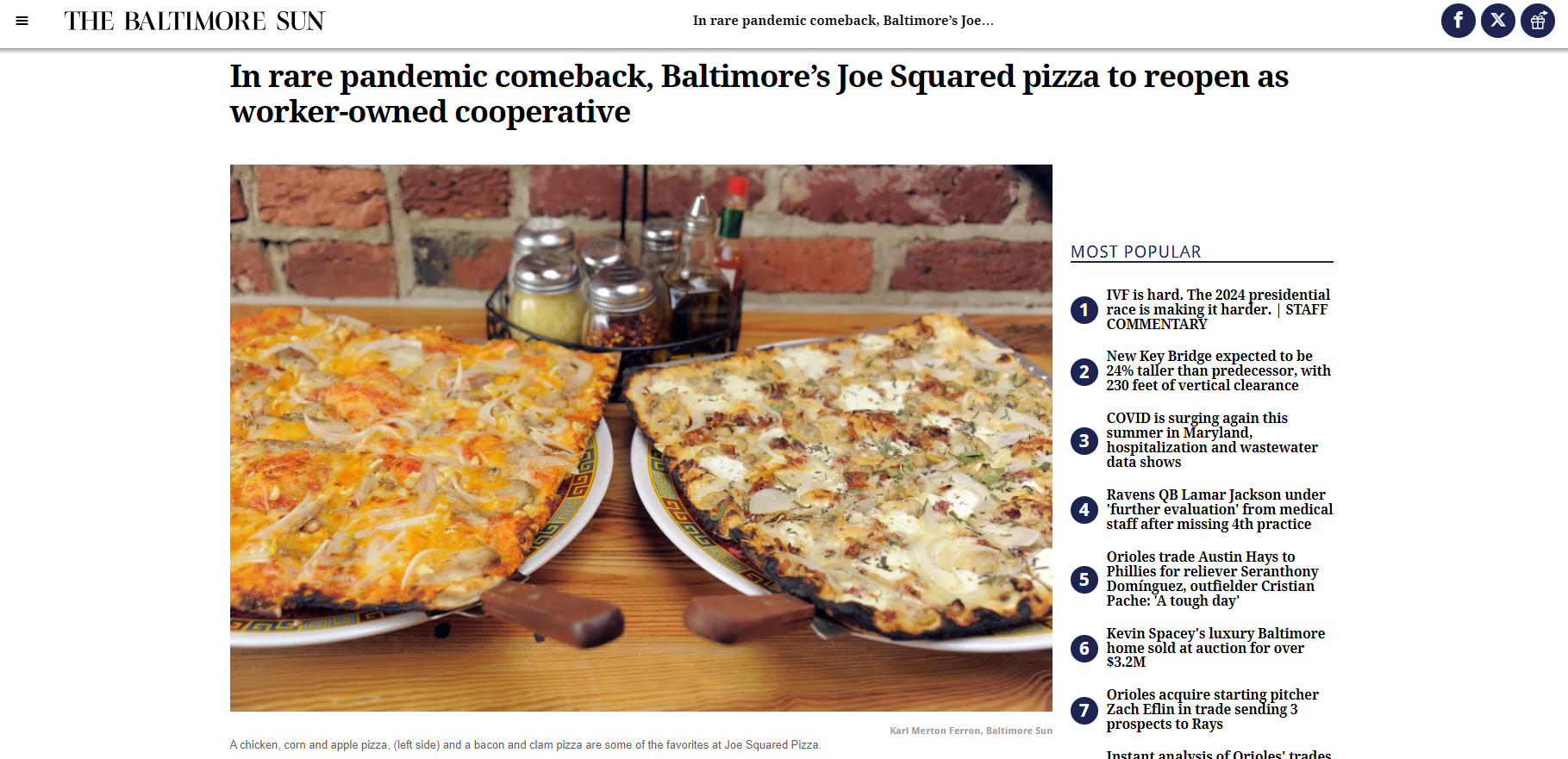

- BRED provided a grant and technical assistance to help Joe Squared, a struggling pizzeria in Baltimore, to transition into a worker-owned business by 13 employees.

- Apis & Heritage invested in converting Accent Landscape Contractors, a landscaping services provider with approximately 120 workers (most of whom are lower-income hourly-wage Latino workers) into a worker-owned business. They did this through a model they call the Employee-Led Buyout (ELBO). Additional financing was provided by the Woodforest National Bank.

More on this process in the Capital Access Providers section below.

Differences between worker co-ops and conversion businesses

The key differences between worker co-ops and conversion businesses can be summed up in this table below:

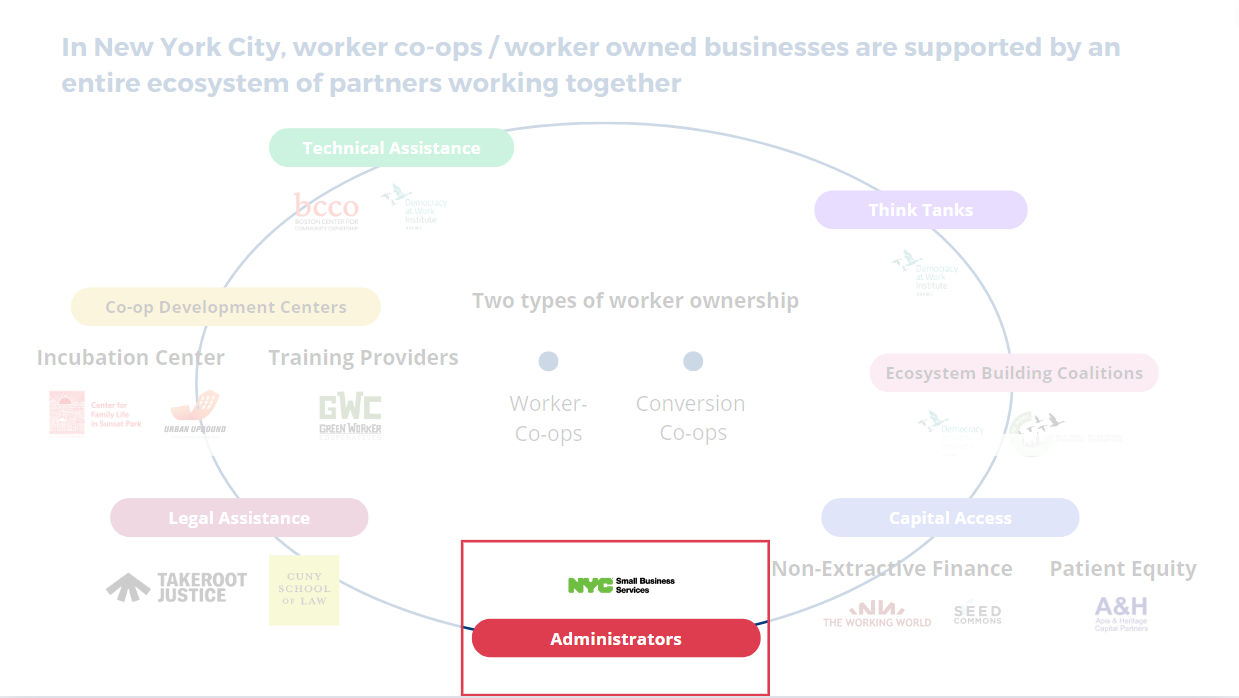

The worker co-op ecosystem in New York City is significantly more mature with more players

In part 1 of this series of articles, I put forth the view that our co-op movement might be limited because it is stewarded by only two organizations - RCS and SNCF.

This became evident to me in New York, where I saw how their worker co-ops and worker-owned businesses thrive within a supportive ecosystem of diverse partners.

Looking at the different stakeholders led me to conclude that two organizations cannot play all the roles that are required to build a supportive ecosystem for co-ops to thrive.

In this section, I will describe each of these stakeholders and the role they play in detail.

Co-op Development Centres

Incubation Centers

I came across two social service agencies playing this role: the Center for Family Life (CFL) in Sunset Park, Brooklyn and Urban Upbound in Long Island City, Queens. Both had a deep understanding of local issues and high trust with community members, who were already beneficiaries of their services and financial assistance programs.

I met Juan and Amalia from CFL's Co-op Business Development Program in my final week in New York and they explained their role in detail to me.

Many of CFL's beneficiaries are undocumented female Spanish-speaking immigrants from Latin America who struggle to find good jobs due to work permits, poor English skills and caregiving responsibilities.

CFL aims to empower these women to achieve the following outcomes through being a worker-owner in a worker co-op:

- Have dignified, stable and secure work

- Earn a living wage

- Have a voice in business operations

- Assume leadership roles in both the co-op and broader community

As many of these women worked daily-rated jobs in childcare and cleaning and the barriers to entry into these industries were low, CFL launched its first two worker co-ops in these sectors.

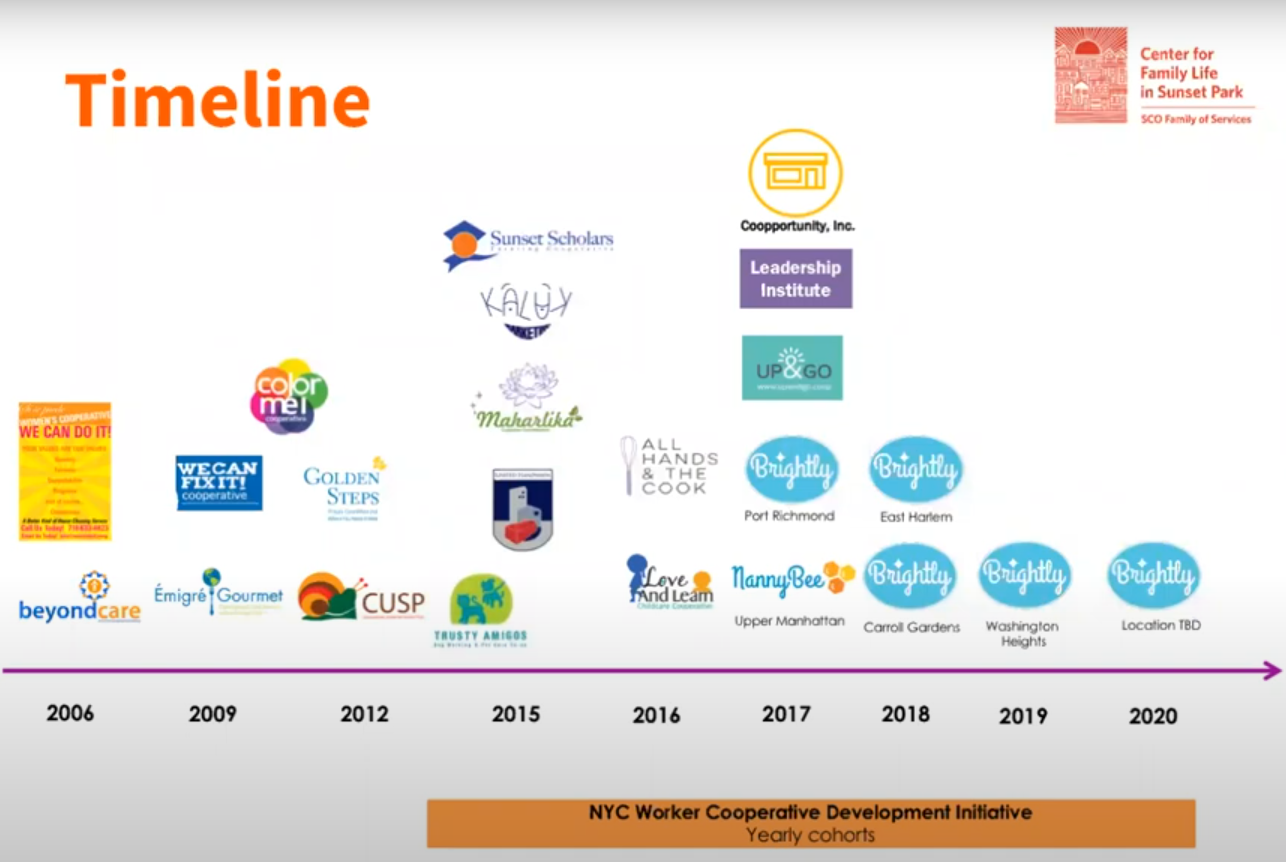

From 2006 - 2021, CFL supported over 20 worker co-ops across various industries, including: eldercare, gourmet catering, dog walking, office cleaning and tutoring.

One notable success was their cleaning co-op Si Se Puede (We Can Do It). CFL gradually decided to focus on expanding proven business models rather than continuously creating new ones.

This approach led to the creation of Brightly, a worker co-op designed to franchise CFL's cleaning co-op model to other interested social service agencies - a first-of-its-kind model in the United States.

Juan and Amalia also shared valuable lessons from their experience as co-op developers:

A long onboarding process is required

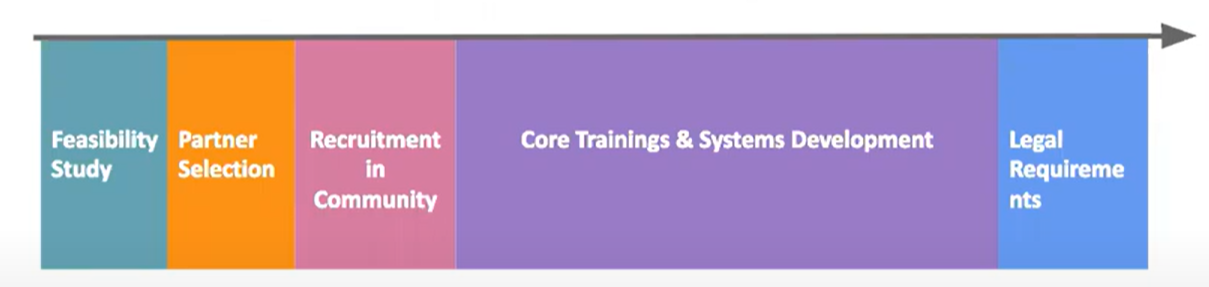

Before launching their worker co-op, CFL and its prospective worker owners go through an 8 - 10 month long process, with the broad steps as follows:

- CFL conducts a market and industry analysis to assess the feasibility of the business idea

- CFL hosts information sessions for interested community members, clarifying that this is an entrepreneurship project that involves risks, and is not a job placement

- CFL selects around 20 - 25 community members for the process. Typically, around 1/3 drop out along the way, leaving around 15 people to be the first worker owners when the co-op launches.

- CFL either trains or connects community members to training providers to learn skills like leadership, financial management and sales. The training is designed to enable them to take concrete steps towards incorporating their business.

- CFL helps community members comply with legal requirements like licenses and acquiring an Employer Identification number (EIN) for business incorporation. It also provides start up funds from its budget.

Technical assistance is crucial and CFL has to commit to journeying with them

After a worker co-op is registered, CFL continues to support its members by:

- Setting up and managing backend business functions like accounting and bookkeeping

- Hiring sales consultants who can help worker owners to sell their cleaning services, so that worker owners can focus on service delivery

- Connecting worker owners with technical assistance providers (see below) who can help with legal advice, business development, etc

- Connecting them with mentors from the cleaning industry or from other cleaning co-ops for advice

- Managing social media pages and implementing paid social media ad campaigns to attract leads for the worker co-op's services

- Giving them templates for contracts, membership manuals, and other important documents that worker owners can copy

CFL does a lot! I asked Juan and Amalia:

Can you really call these women business owners if a significant portion of the business development work is being done for them?

To which they replied that it is unrealistic to expect the women to have these skills because they may have been denied opportunities to go to college or workshops due to their socio-economic background.

CFL focuses on what they can do first, such as distributing flyers to promote the business at local events or participating in media interviews. CFL aims to gradually build their skills over time, with an estimated 2-year timeline before they can assume roles currently filled by consultants.

Therefore, continuous support from CFL is crucial throughout this period.

Maru Bautista, a former staff member of CFL's Co-op Development Program, explains the CFL incubation model in a video from 2020, video credit: CFL

Respect the decisions that worker-owners make, even if they are not aligned to what CFL staff may think is right

For example, CFL has been trying to convince members of their cleaning co-ops to charge a subscription model instead of one-off cleaning fees. Subscription fees tend to be lower than one-off cleaning fees but could guarantee the co-op recurring revenue and increase the stability of its cash flow.

CFL's staff members researched how other for-profit cleaning companies were adopting a subscription model and prepared some basic financial projections that showed how a subscription model could generate higher profits in the long run.

However, even after reviewing this information, the women still decided to stick to charging one-off cleaning fees, preferring higher prices in the short term over more stable revenue in the long term.

"Ownership means they make decisions and take responsibility for the consequences of these decisions. Our duty is to prepare the necessary information and answer their questions to support them with making a more informed decision.

Their responsibility is to ensure that they hear us out and are able to repeat it back to us so we know they understand. But ultimately, it is their choice to make," Amalia told me.

I found this to be an extremely interesting example of community ownership and asset-based community development.

As a Singaporean, I grew up with this idea of optimizing everything. Would I be able to surrender control to community members and accept a decision I think is wrong?

If I believe in the asset-based community development philosophy that people are the experts of their own lives, do I also believe that they are the experts of the solutions to the problems in their lives?

Conflict mediation is a core part of a co-op developer's work

In CFL's experience, conflicts in worker co-ops often arise from issues with fair division of labour and remuneration.

Because worker co-ops operate on joint-decision making and co-ownership, member relationships are crucial for success, unlike a typical business that can just let people go.

CFL helps its co-ops to develop grievance management and member exit procedures, on top of providing direct mediation services between members in conflict.

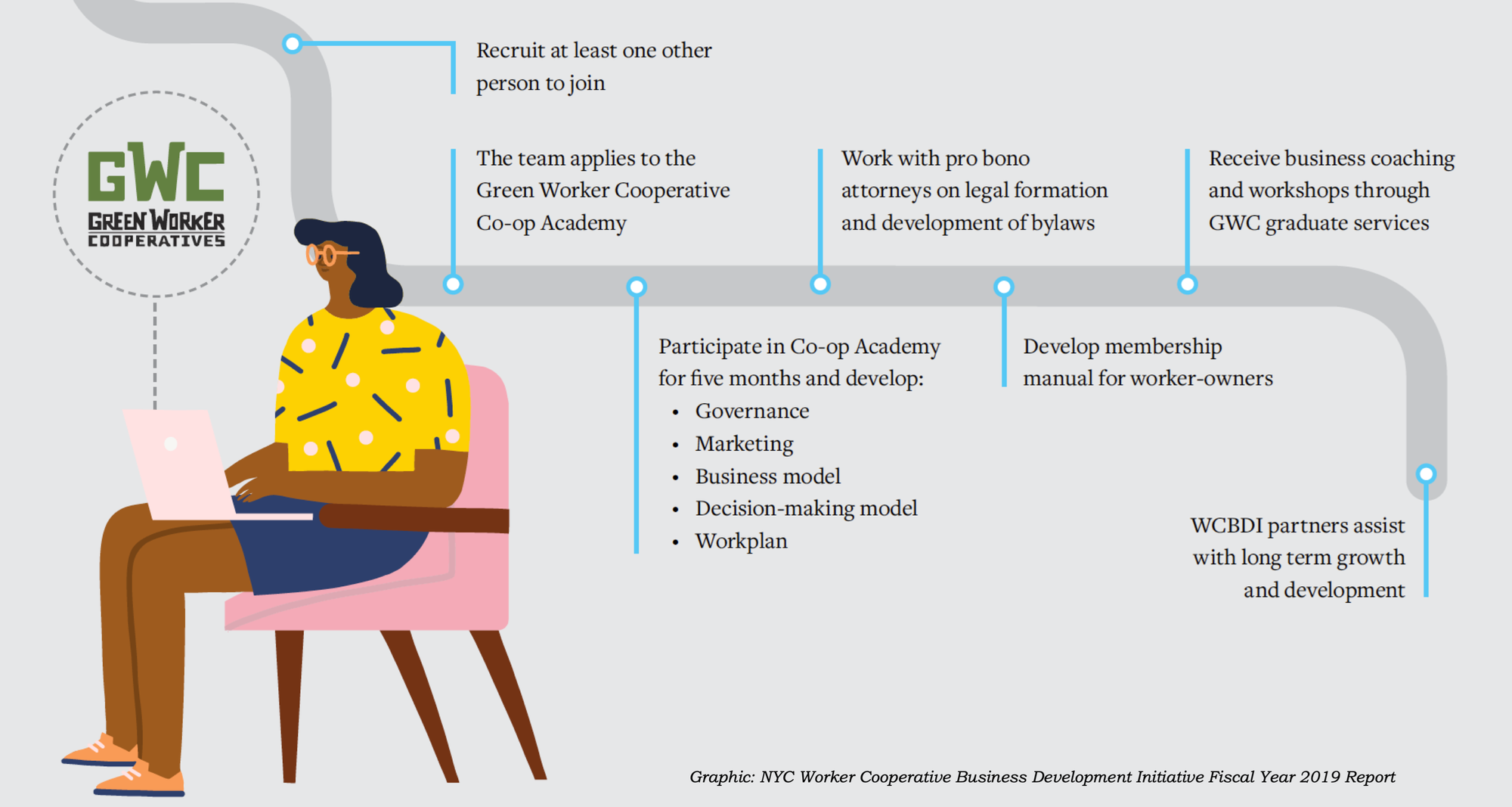

Training Providers

Green Worker Cooperatives (GWC) offers a 5-month intensive bootcamp to help teams of entrepreneurs launch their co-ops. The program includes:

- Modules on governance, marketing, business models, shared decision making and creating workplans, taught by experts from active worker co-ops

- Business support services like legal incorporation and access to financial services

The program is provided at no cost due to funding from City of New York's Worker Cooperative Business Development Initiative (see below) and other funders.

Besides their Co-op Academy course, GWC also offers free workshops on co-ops for youths and adults across New York City that are available in both English and Spanish.

Technical Assistance Providers

Technical assistance providers like the Boston Center for Community Ownership (BCCO) and the Democracy at Work Institute (DAWI) play a crucial role in supporting both start-up and conversion co-ops.

Where organizations like CFL help to spot potential business opportunities and suitable members for the co-op, BCCO provides practical help in various areas:

- Business model development - help co-ops to write a business plan, prepare financial projects to determine feasibility, perform market sizing to understand income potential, and set up clear and organized systems for financial management, sales, marketing, operations and administration

- Income generation - help co-ops to find loans, grants and investments to generate sufficient financing to pay for startup costs and any anticipated early losses. They also provide business coaching to ensure the co-op gets to profitability within the planned timeline

- Design governance structures - design a governance structure that will allow for democratic decision making but is not overly complex, develop by-laws and policies and implement training programs to onboard subsequent members

Organizations like BCCO typically engage in long-term (3 to 5 years) partnerships with co-ops. This level of commitment requires advance planning and fundraising, with responsibility shared between BCCO and the co-op.

For conversion co-ops, technical assistance providers may do the following:

- Initial feasibility assessment - conduct interviews to gauge interest levels amongst workers and the current owner, organize educational workshops on co-operative models and perform business analysis to assess feasibility and estimate sale price

- Setup governance structures and navigate financing - design governance structures including by-laws, policies and decision-making levels; work with lawyers and accountants to prepare necessary documents for the conversion and secure financing for the purchase price

- Provide support post-conversion - provide organizational development support to worker owners as they navigate the first year of ownership

Capital Access Providers

Overview of the "Patient Equity" stakeholder

At the Democracy at Work Institute's 10 year anniversary celebration, I sat at the same table as Kyle Chin-How, who introduced himself as the Head of Business Development for Apis & Heritage Capital Partners (A&H), a social impact private equity firm that empowers workers of color to own their futures.

"Why would a private equity firm be interested in cooperatives which aren't entirely profit maximizing?" I blurted out.

"Because cooperatives are good business," he responded.

This brief exchange led to us having a deeper conversation later on at a cafe near the New York Public Library, where Kyle explained A&H's work to me. A&H finances the acquisition of profitable companies with significant numbers of BIPOC employees from retiring owners / founders and converts them into 100% employee-owned enterprises using an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP).

In today's America, 60% of Black workers have $0 in retirement assessments, making them vulnerable to financial insecurity as they age and without resources to pass on to the next generation.

A&H expects an average worker who benefits from an A&H-assisted buyout to accrue retirement savings of $70,000 - $120,000 each, which can be life changing. Other benefits include:

- Enterprises that are 100% ESOP-owned pay zero federal taxes and in 44 out of 50 US states, zero state taxes, which increases the business' cash flow after transitioning to employee-ownership

- Company sales, employment and productivity increase by more than 2% per year after implementing an ESOP

- Most employees at an ESOP report higher job satisfaction and a greater sense of purpose

- Millennial workers at ESOP companies have 33% higher median income from their wages compared to millennial workers at non-ESOP companies

In particular, A&H seeks companies:

- With at least $2 - 6 million in EBITDA

- With 40 or more employees, where at least 1/3 are BIPOC

- Focus on essential service sectors like landscaping, plumbing, food processing, commercial cleaning, healthcare and transportation

Conversion process and key roles

Unlike traditional private equity firms, A&H does not take equity stakes in the companies they invest in. Instead, their investments are structured as debt (from what I can understand), which the companies repay with interest.

They call this approach the "employee-led buyout" (ELBO). A&H has invested in three companies so far and aims to invest in up to ten, targeting a 15% net internal rate of return (IRR) and 2.0 gross multiple on invested capital (MOIC) for its investment fund.

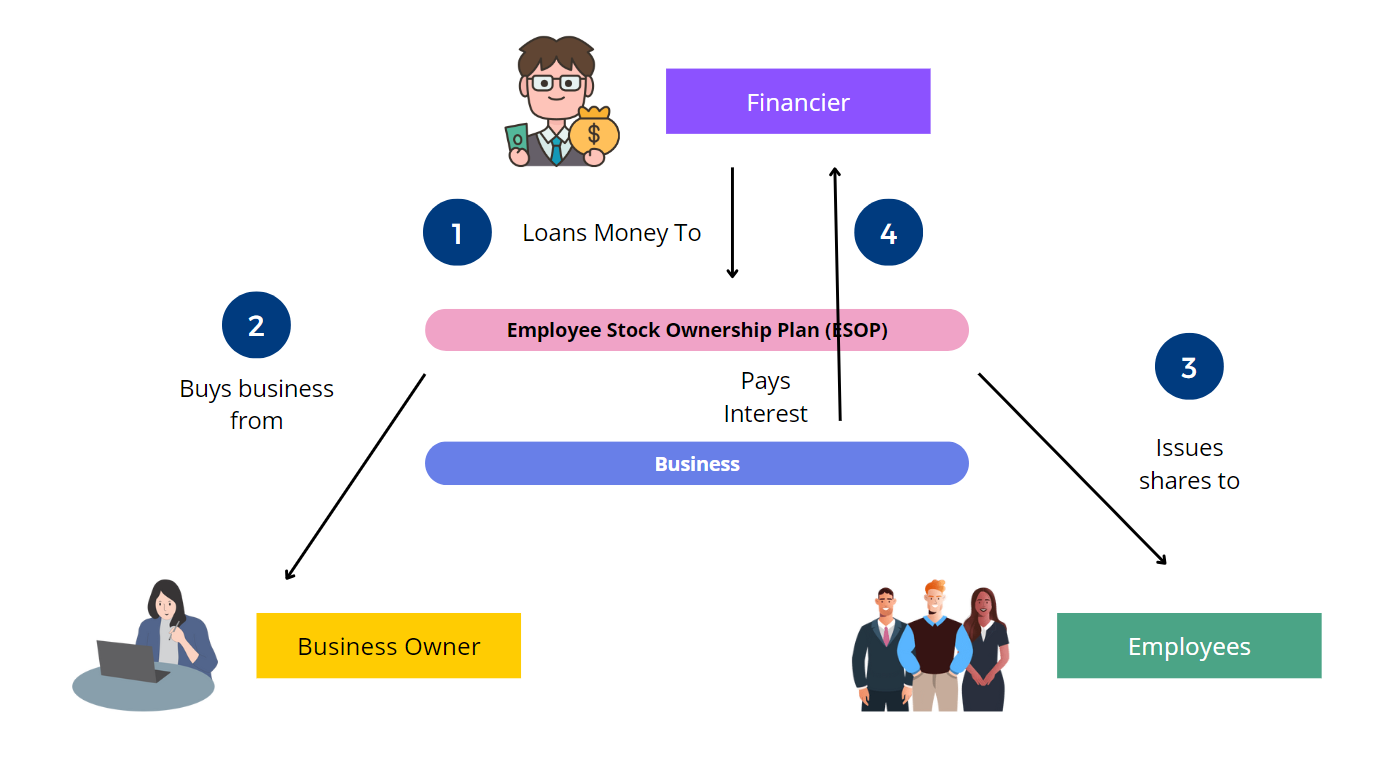

Here is the ELBO process illustrated in a graphic, from what I can understand:

Employees must adjust psychologically when transitioning from salaried employers to co-owners. To support this shift, A&H partners with the Democracy at Work Institute to support and train their portfolio companies in building a culture for employee ownership.

A&H remains involved in governance and oversight, advising the management team for up to five years until repayment is complete.

But why would business owners want to sell? Here's what Cameron Stevens, the founder and owner of Accent Landscape Contractors had to say:

"I could have sold my business to a competitor or private equity, but I know what can happen next – the culture changes and people get laid off. I didn't want that for my employees. They are like family to me, and they helped build the company.

Or Brian Wilkie, co-founder and owner of Apex Plumbing, another company that Apis & Heritage invested in:

We built a great company over 35 years through dedication and the hard work of our team. By converting our company into an employee-owned business, we have provided an opportunity for all team members to reap the benefits of their hard work going forward through stock ownership. The future is literally in their hands, and we couldn't be more excited for our company and its new owners, our employees.

Overview of the "Non-Extractive Finance" stakeholder

Similar to patient equity firms like A&H, non-extractive finance stakeholders provide loans to support co-ops, either as start-up capital or for converting existing businesses into worker-owned entities.

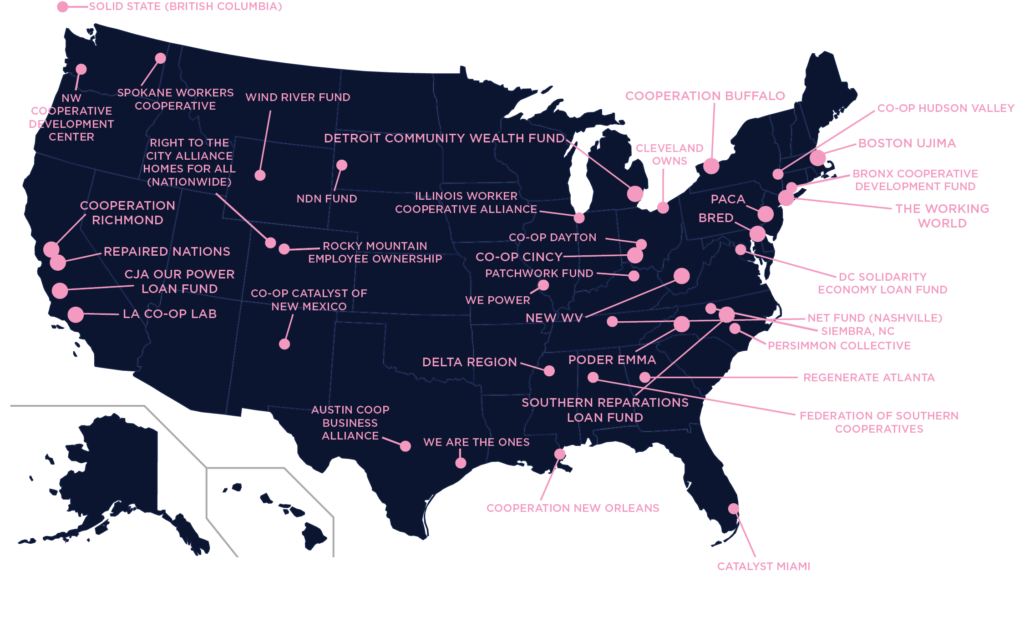

One example of such a stakeholder is Seed Commons, a national network of non-extractive loan providers that support local co-ops. It aggregates investments from family offices and other investors, which it then deploys through local partners across various US states, such as The Working World in Brooklyn, New York City and the Baltimore Roundtable for Economic Democracy (BRED) in Baltimore, Maryland.

These local partners make non-extractive loans to co-ops in their cities and often engage in co-op development and technical assistance work.

Some, like The Working World, may also raise additional funds from investors around the world for deployment. Since its inception in 2016, Seed Commons has received over $15 million USD in investment and made 100+ loans through 30+ local partners.

The "non-extractive finance" philosophy

But what exactly is a non-extractive loan?

Seed Commons defines it as: "the returns to the lender never exceeding the wealth created by the borrower using the capital" or more simply: "a borrower will never be worse off after taking the loan."

Unlike traditional finance, where high interest rates can leave borrowers worse off - such as losing their homes over credit card debt or being burdened with long-term student loans - a non-extractive loan ensures that the borrower is not financially harmed by the loan.

Seed Commons offers various types of loans, including: secured asset purchase loans, working capital loans, line of credit loans, etc, all guided by a non-extractive philosophy.

This philosophy manifests in the following terms:

- Repayment tied to profits - Borrowers only repay interest or principal if they can cover their operating costs, including market-rate salaries. If there are no profits, no repayments need to be made.

- No personal guarantees - collateral is not required unless the asset is purchased with the loan funds

- No credit scores - Instead of credit scores, Seed Commons relies on strong relationships between local partners and potential borrowers to assess reliability

Loans are typically given to individuals from marginalized communities, including: Black and Brown families, women and non-binary people, Indigenous communities and low-income individuals.

How Seed Commons ensures its sustainability

When profit is generated by the co-op, Seed Commons practices a profit sharing agreement, which it uses to cover the labor of their staff and ensure it can issue new loans to future borrowers.

The profit sharing agreement has the following characteristics:

- At least 50% of profits generated from the loan must stay with the borrower.

- A total annual interest rate of 7% if applied to the outstanding principal, calculated monthly, until the principal is repaid.

- In profitable years, the co-op will share an agreed upon % of profits with Seed Commons

How does Seed Commons mitigate risk?

Just like business investors, Seed Commons mitigates risks by:

- Rigorously assessing the business plans of co-ops seeking loans

- Working with the co-op to improve their business plan

- Offering technical assistance after the loan to ensure co-ops have the support they need to succeed

This approach aligns the interests of both borrower and lender, as they are both incentivized to help the co-op succeed. By addressing business issues early and providing timely support, Seed Commons maintains a low write-off rate and a strong track record of success.

Think Tanks

Produce knowledge useful for co-op development

Organizations like the Democracy at Work Institute (DAWI) produce research to support and advance the field of co-op development. Some examples include:

- Research studies to advocate for favorable policies and conditions for the co-op movement - such studies may investigate the economic and social benefits of co-ops, evaluate their effectiveness in job and business retention and assess the suitability of particular types of businesses for worker co-op conversion. For example, previous studies found that worker owners in a co-op earned an average of $3.52 per hour higher than their previous jobs in traditional businesses, have 92% higher household net worth and are less likely to be laid off.

Such data helps advocates of the co-op movement to build a stronger case to attract increased support from funders and government agencies.

- Develop best practices and toolkits for ecosystem players - DAWI documents best practices in key areas like governance and equity structure to assist co-ops in their formation. They also develop practical toolkits, including business valuation and financing tools, specifically for worker co-op conversions.

Help interested city leaders and policymakers to design supportive initiatives and policies for more worker co-ops to form

Traditionally, local governments focus on two key interventions to address income inequality and support vulnerable populations: entrepreneurship and workforce development.

However, using worker co-ops as a strategy to provide stable employment and business ownership for low-wage workers, women, immigrants and BIPOC individuals is still under-recognized, despite its proven effectiveness.

In addition to conducting research, DAWI also operates programs like the SEED Fellowship, a year-long initiative that helps city and community leaders create favorable strategies and policies for worker co-ops.

Zen Trenholm, the Senior Director of Employee Ownership Cities and Policy at DAWI, explained the key components of the SEED Fellowship to me:

- Typically four fellowship cities are selected - each city's Mayor then forms a team of four: comprising two city fellows (typically Executive Directors from economic development agencies), a coordinating fellow (typically a mid-level manager who will serve as a project manager) and a community fellow outside the government who could be a co-op leader, capital access provider or technical assistance consultant.

- DAWI works with selected fellows to shape a clear problem statement - DAWI helps fellows identify local challenges that worker ownership could address. This then leads to a clear problem statement such as: "how might we preserve minority-owned legacy businesses through conversion to worker ownership?"

- Bring fellows to actual worker co-ops to see for themselves - fellows visit worker co-ops and stakeholders within each of the four fellowship cities to gain firsthand insight into worker ownership and real-life case studies.

- Fellows work on their projects for the rest of the year - with DAWI providing technical assistance and access to guest speakers who share best practices. Examples of past projects include: building a registry of legacy businesses and developing a commercial site acquisition program for co-ops to buy city-owned property for their operations.

Best practices that cities looking to encourage more worker co-ops can consider

Zen highlighted best practices from cities that have successfully fostered worker co-ops:

- Raising awareness is a key step - educate stakeholders providing key ancillary functions that worker co-ops need - such as banks, insurance companies and legal firms - about worker ownership as a viable and legitimate business model

- Start with a small pilot - launch a small worker co-op that can provide services which the city can contract out to, such as a human sanitation services co-op, as a proof of concept

- Integrate worker co-ops into city procurement policies - such as requiring some level of employee ownership for vendors applying for city contracts

- Make sustained investments in technical assistance - ensure ongoing funding for co-ops to access essential technical assistance support, as seen in successful cities like New York City. Technical assistance support is typically unaffordable for many worker co-ops and government agencies may not have the expertise to provide the technical help that worker co-ops need.

An interesting anecdote I observed was the personal stories that people shared about DAWI's impact on their personal and professional development, in particular the founding Executive Director Melissa Hooever and Director of Education & Training Rebecca Bauen:

"They were interested in me as a person and when I was experiencing doubt in my work, they showed me how I was an important part of the ecosystem and took my calls at any hour..."

Legal Assistance

Organizations like TakeRoot Justice and the City University of New York (CUNY) School of Law's Community & Economic Development Clinic offer crucial legal support to co-ops.

For example, CUNY's clinic allows student interns to gain practical experience by representing worker co-ops on legal matters such as entity-type advice, legal formation, governance, contracts, tax exemption, employment, and other operational issues.

Administrators

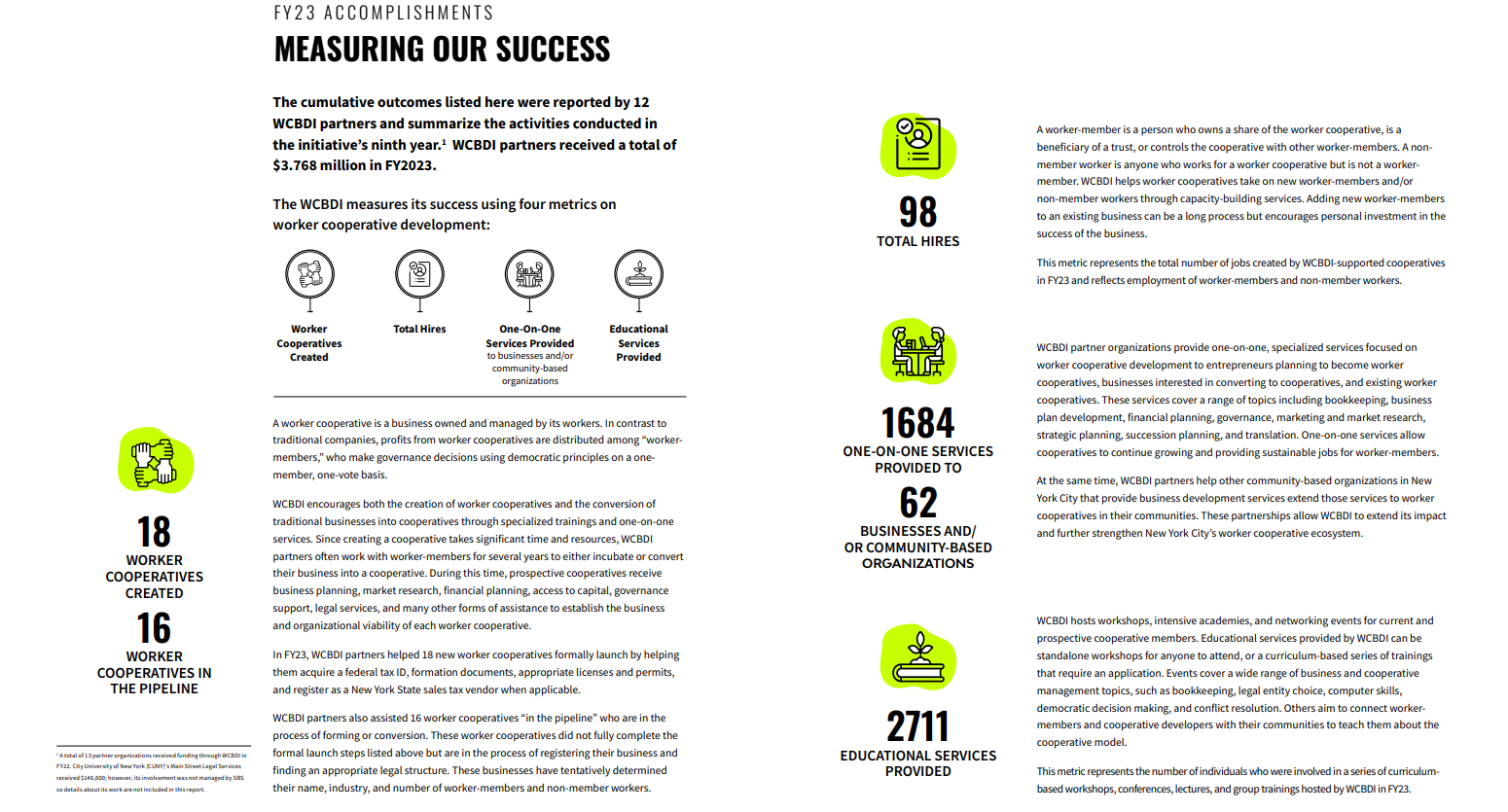

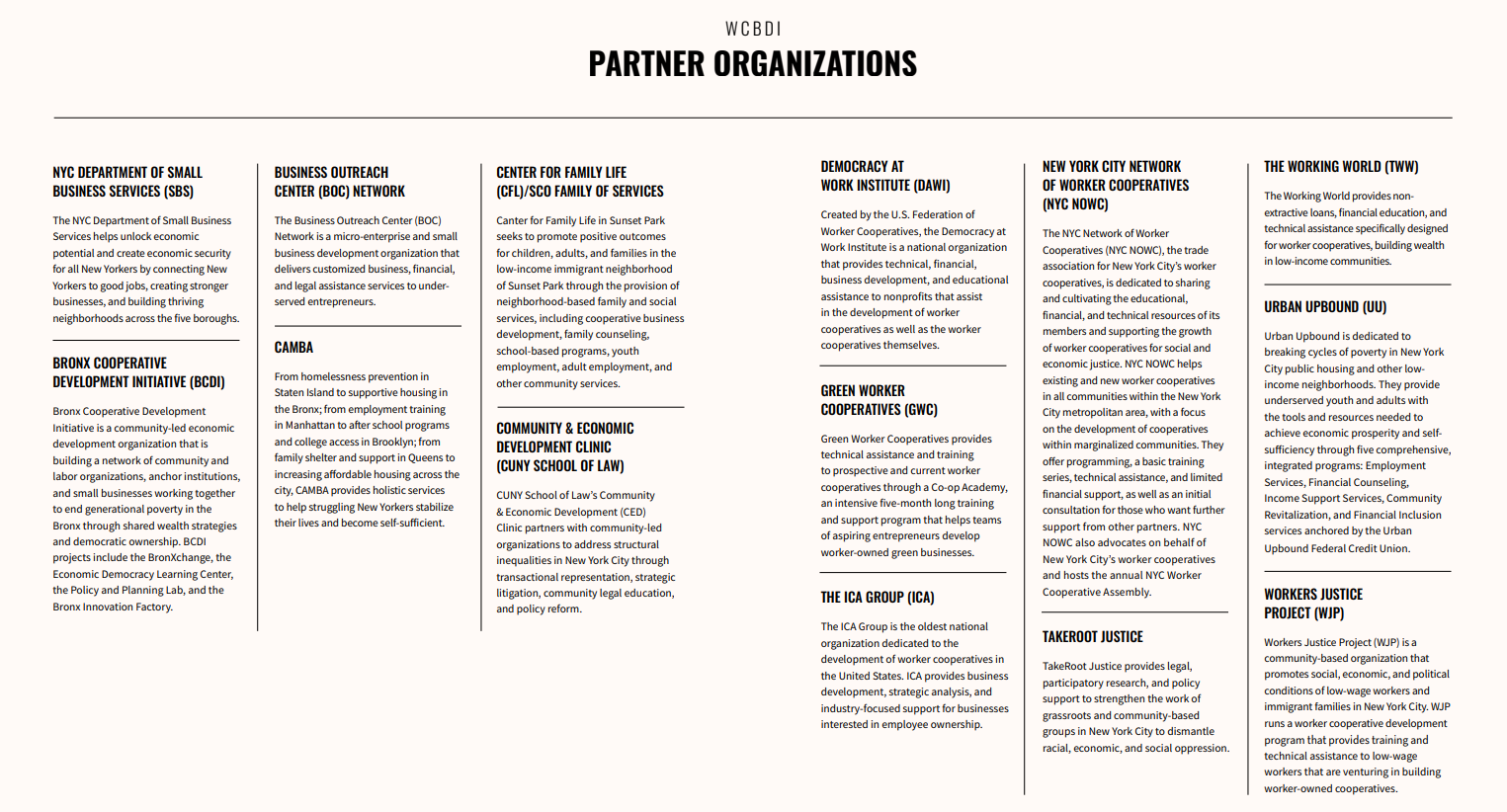

The NYC Department of Small Business Services (SBS), a government agency, has a Worker Cooperative Business Development Initiative (WCBDI), which has a similar mandate to the Singapore National Cooperative Federation (SNCF).

I spoke to Miguel Modesto, who explained to me that the WCBDI receives discretionary funding from council members in the NYC's city council (akin to Members of Parliament in Singapore's context) to contract various partners to provide the following services:

- Converting an existing business to a worker co-op with DAWI

- Training on basic business skills for how to run a worker co-op (e.g. how to create invoices, pay taxes, do marketing, etc) with Green Worker Cooperatives

- One on one coaching to help worker owners operate and grow their co-ops with Centre for Family Life

- Legal support on matters like incorporation and permits with Takeroot Justice and CUNY School of Law

- Specialized financing support for worker co-ops with The Working World

I was really impressed with how WCBDI presented their impact and the results they achieved - 18 worker co-ops created and 16 worker co-ops in the pipeline in just FY23 alone!

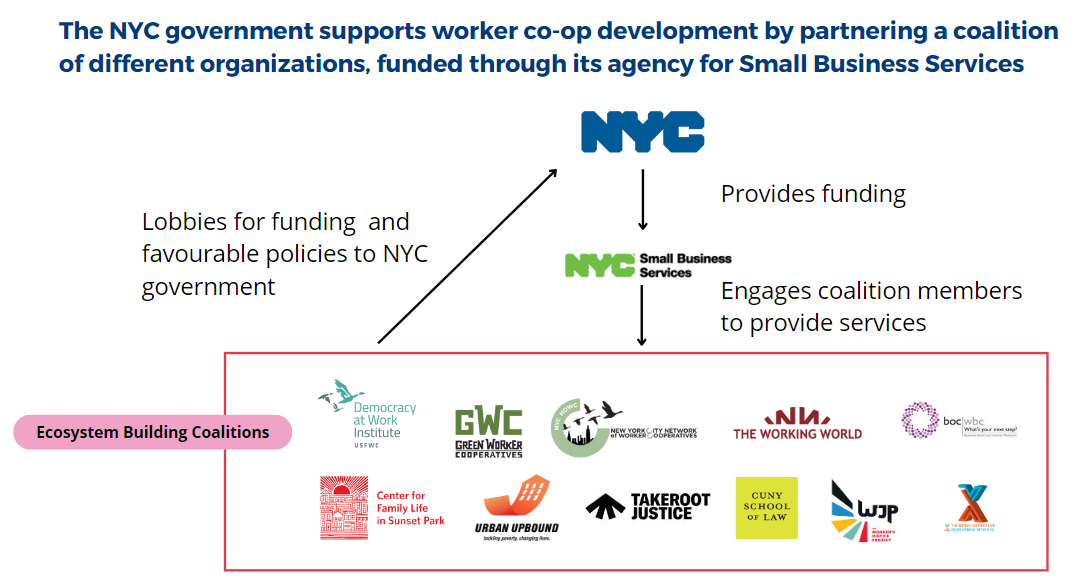

Ecosystem Building Coalitions

Raybblin explained to me that the coalition engaging with the WCBDI was formed in 2014 and DAWI plays a leadership role. Each year, it lobbies the New York City government for better policies and grants to grow the ecosystem for worker co-op development.

The grants are used to subsidize the costs of providing services such as business skills training for worker owners of a co-op incubated by the Center for Family Life.

During COVID when funds were tight, the coalition members jointly raised $100,000 to keep the work of individual members alive.

Field Building typically involves: (i) research to generate data, (ii) developing capabilities of stakeholders, (iii) educating funders to support the work, (iv) cooperating with other stakeholders to share resources and (v) developing a common vision that unites different stakeholders. More on this in Part 3.

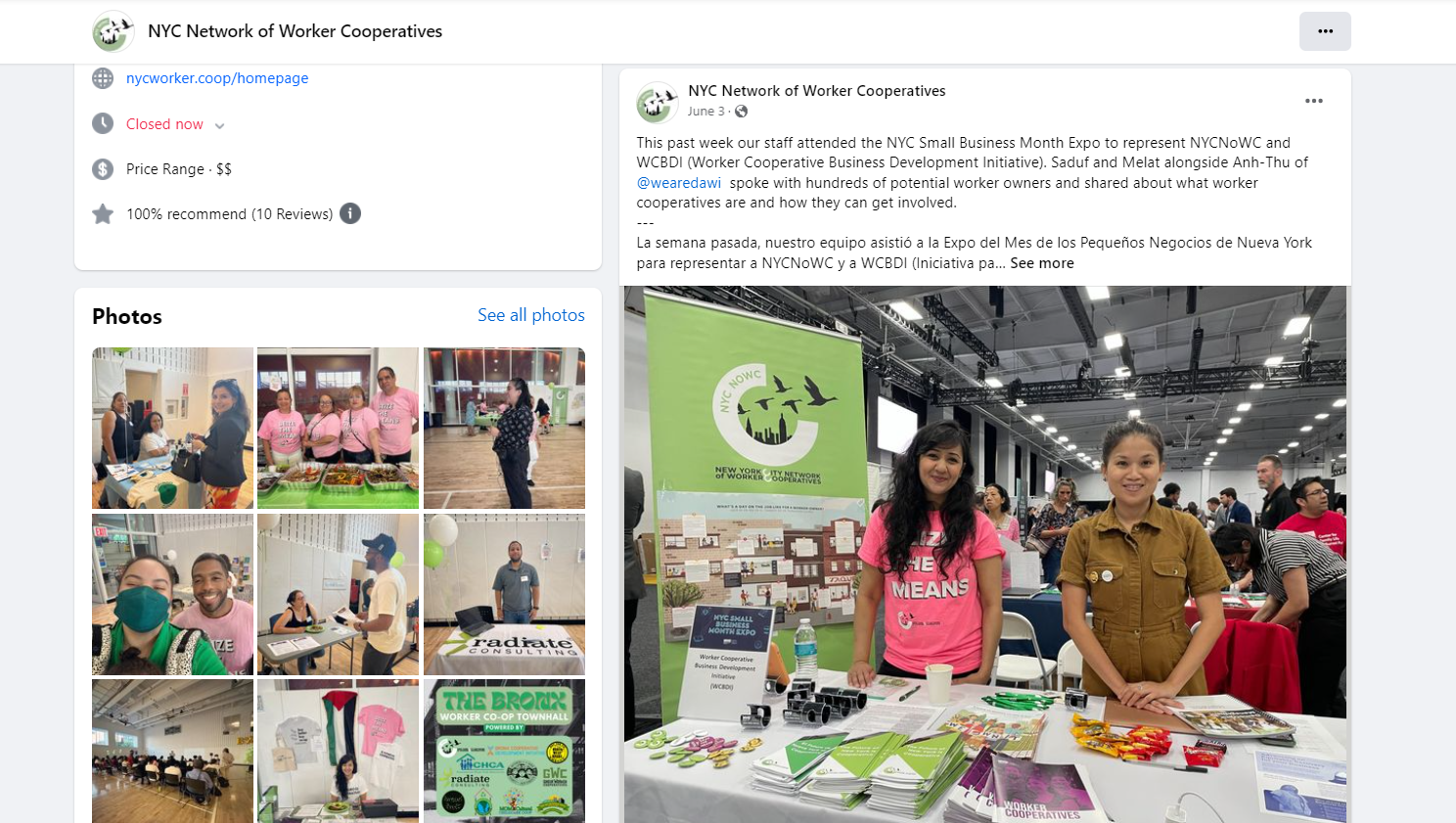

One of the members of this coalition is the New York City Network of Worker Cooperatives (NYC NOWC), a trade association with over 70+ worker co-op members that seeks to promote worker co-ops in NYC through the following:

- Lobbying for public funding and favourable legislation at city (New York City), state (New York State) and national levels (to the United States Federation of Worker Co-operatives)

- Increase visibility of worker co-ops through organizing an annual conference, attending roadshows and hosting public events

- Engage service providers to provide marketing, website, book-keeping, digital media and pro bono legal services to worker co-ops in NYC

Key Reflections from New York

Singapore's co-op ecosystem needs more players

Returning to the point I made early on in this article, the New York City worker co-op ecosystem is notably more developed, with a coalition of diverse stakeholders supporting co-ops through various roles, from incubation to capital access.

In my humble opinion, we currently only have one stakeholder playing an active role to promote co-op development in Singapore and that is SNCF who plays the administrator role. (RCS mainly plays a governance role)

It's not practical to expect SNCF alone to manage all aspects needed for co-ops to thrive, such as incubation, capital access, thought leadership, technical assistance, etc.

The people I met in New York City seemed very passionate about co-ops and proud to call themselves co-op members

Perhaps it is a cultural difference that we Asians are more reserved but what struck me was how passionate the people working in the above-mentioned stakeholders were about co-ops.

Many of them have either founded or are members of worker co-ops and were deeply proud to call themselves co-op members.

Raybblin repeated to me several times her belief that worker co-ops were a vehicle for economic democracy and social justice and it was hard not to be inspired by the conviction and passion she had.

They bring a different energy to their work which is unlike anything I have experienced in Singapore.

There is an explicit role for co-op developers and technical assistance

Several of their co-op developers are charities like the Center for Family Life and Urban Upbound who already provided services and enjoy high levels of trust with vulnerable communities who are often people who can benefit from participating in a worker co-op.

Furthermore, the New York City ecosystem recognizes that people from vulnerable communities will need technical assistance like business modelling and creating financial projections to be able to start co-ops and therefore, provides this support to them.

While SNCF does provide some general incorporation advice to people who wish to start co-ops, what if it partnered neighborhood-based social service agencies like Beyond Social Services who enjoy high trust with low-income families, to explore using worker co-ops as a vehicle for economic inclusion?

What if it also provided them with the technical assistance they need to get started, which is often something that these families lack access to?

The CCF is parked under MCCY and not MTI

The CCF and RCS are under the purview of the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY), which also houses the office of the Commissioner of Charities, who also serves as the Executive Director of RCS, instead of the Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI), which specifically looks at promoting economic development and businesses.

To me, the downside of this is that they may have a low tolerance for risk that is necessary for business innovation when it comes to disbursing grants and lack the skillsets to provide business development advice.

In contrast, the agency responsible for promoting co-op development in New York City is housed under their Department of Small Business Services, which already has experience helping small businesses to grow.

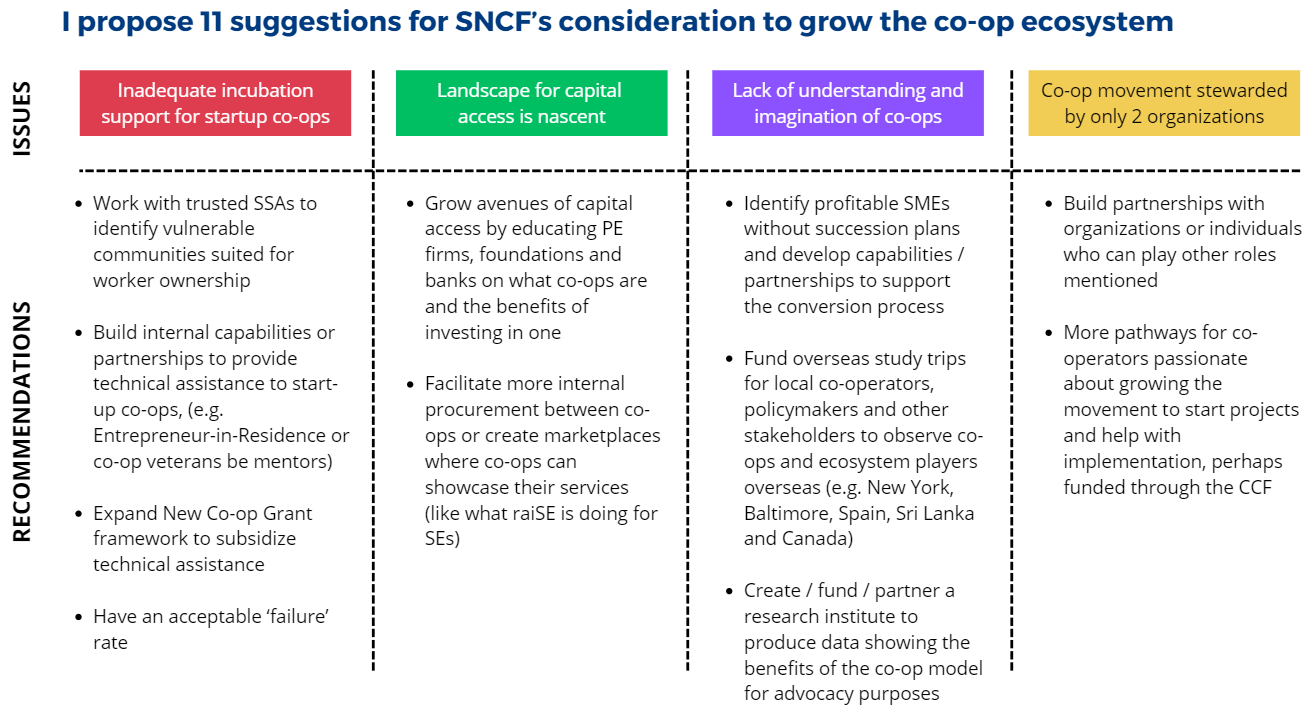

Recommendations for Singapore

So what can we do to nurture an even more thriving ecosystem for co-ops in Singapore?

In the final part of this series, I will propose 11 suggestions that could be useful.