Prevent gender based violence by creating a safe space for men

We analyze a successful program to prevent gender-based violence in Zambia through creating a safe men for men to talk about their emotions and perspectives.

Gender Based Violence in Zambia

Preventing gender-based violence is a serious issue in Zambia, with Zambians ranking it as the most important women's rights issue that their government and society must address, ahead of unequal access to education and low female representation in government.

Gender-based violence can be physical, mental, social or economic abuse against a person because of their gender, resulting in physical, sexual or psychological harm and suffering to the victim. Women in Zambia experience a variety of gender-based violence, sometimes from their husbands or partners, such as battery, sexual abuse, child marriage or infidelity, depriving them of their right to health and wellbeing.

The statistics are sobering: 36% of Zambian women above age 15 have experienced physical violence and 20% have suffered sexual abuse before age 18 - among the highest rates of gender-based violence in the world.

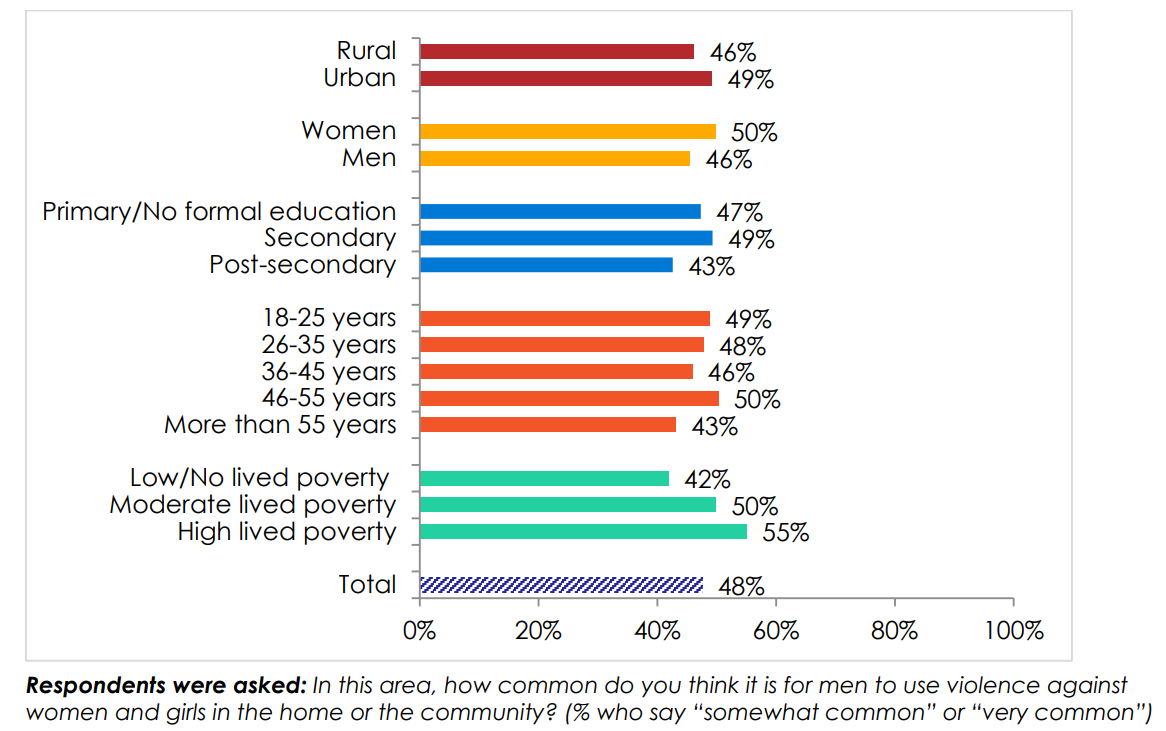

Although most Zambians say it is never justified for a man to use physical force to discipline his wife, a majority also say that violence against women and girls is common in their communities.

Women continue to suffer in silence because many incidents of gender-based violence go unreported, either because they think domestic violence is a private matter to be handled within the family or they fear criticism, harassment or shame by others if they report it to the authorities.

While there are national laws against gender-based violence and a variety of programs to prevent gender-based violence such as shelters and counseling services, they are often under-funded, poorly coordinated and geographically limited, failing to reach many of Zambia’s gender-based violence survivors.

Whilst working for 7 years in different NGOs on projects for HIV, child protection and economic development, Peter discovered that most interventions for gender-based violence tend to be focused on women, whether it is workshops that teach women how to defend themselves and report their abusers or services that provide shelter and counseling to women post-abuse.

“Men have a significant responsibility in causing gender-based violence but they are rarely engaged to be part of the solution,” he said.

As he started talking with male perpetrators of gender-based violence to understand why they hit women in their families, Peter discovered that the root cause was that they did not have a healthy way to address the discomfort they feel when their male pride feels threatened.

Some men shared stories about how they hit their wives when they said: “What do you expect me to do with the little money you give me?” Or when their wives questioned them about coming home late at night after spending the evening drinking with their buddies at the pub.

“As I listened, I realized they felt emotions like guilt for not being a good provider or resentment at missed opportunities in life but because they did not have a healthy avenue to deal with these emotions, it manifested as anger in striking their wives,” said Peter.

A majority of these men were raised with the belief that men can only be strong. Crying or asking for help is a sign of weakness and should be avoided. In Zambia, men are seen as heads of the household with power to make decisions for their family but they are rarely educated about what being a man means and how they should relate to women.

It doesn’t help that many boys grow up with absent or abusive fathers and they resort to physical violence when they come into conflict with women because this is the only thing they know.

“They kept repeating that nobody was listening to them and I realized these emotions were very uncomfortable and all they want is for someone to acknowledge and listen to them,” said Peter.

Solution: Prevent Gender Based Violence through men as key actors

Peter believes that helping men and boys learn about positive masculinity through good role models can be a very effective community intervention to reduce gender-based violence. What if we could create spaces where men can share the emotions they feel; be listened to and guided by positive male role models to address these emotions in a healthy way?

Growing up without his father, Peter experienced first-hand the transformative power a positive male role model had on his life. While some of his friends engaged in drugs, physical violence and sexual misconduct, the men in his church taught him values about what it meant to be a man and held him accountable to good behavior, helping him to navigate through life’s temptations and challenges.

So in 2021, Peter created the Men’s Boardroom, a series of conversations where around 25 adolescent boys or men gather weekly to talk about serious issues like family planning, physical abuse and substance abuse, much like how men in the corporate world would talk about serious business issues in a Boardroom, supported by a facilitator.

“These issues typically stir up emotions in men that if not addressed healthily could lead to gender-based violence,” said Peter.

The sessions mainly cater to three groups of men: (i) Adolescent boys aged 10 - 19, (ii) young men aged 20 - 29 and (iii) older men aged 30 years and above.

Before the Boardroom sessions start, the adolescent boys and young men groups develop a ‘workplan’ for topics and activities they would like to see in these sessions and Peter helps to review it. This helps them to develop planning skills and confidence in their decision making abilities.

Then, they meet for 2 hours every Saturday for up to 6 months to talk about topics such as: positive relationships with girls, substance abuse and sexual health, guided by a facilitator. A male mentor with experience in these topics is also invited to speak.

The sessions for older men are run in one rural town and the topics revolve around family planning, intimate partner violence and suicide. Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) are also discussed because they can also be a form of gender based violence, given that men are more likely to have multiple sexual relationships and therefore, more likely to transmit STIs to their female partners.

The Boardroom sessions have been running weekly for 2 years now without an end-point. Looking forward, Peter hopes to develop more boys and men to become peer mentors or facilitators who can facilitate a discussion on the topics raised in the Boardroom.

He also wishes to adapt content from other programs such as Coaching Boys Into Men, an evidence-based violence prevention program that engages young men in discussions on relationships, masculinity and mental health through sports, into the Men’s Boardroom sessions.

“Beyond gender-based violence, many other issues across Africa like teenage pregnancies, child marriages and substance abuse are mostly enabled by men and boys. If we heal the man, could we also make a positive change in these other issues,” Peter wonders.

Impact Measurement

Peter’s ultimate aim with the Men’s Boardroom is to prevent gender-based violence and see a reduction in the number of gender-based violence cases in communities where the Men’s Boardroom is facilitated but that will take a number of years to be observed. In the interim, he measures the following metrics to understand if he is making progress:

Improve knowledge on gender-based violence related issues

Before each Men’s Boardroom session, he conducts a pre-program assessment on the knowledge that participants have on the particular issue being discussed (e.g. violence and abuse). Questions such as: “rate your current understanding of what gender-based violence is” are asked. After the session, participants are invited to complete a post-program assessment with the same questions to understand if there is an increase in awareness or knowledge of the issues.

Document success stories

These could be stories of participants adopting more positive ways of managing conflict with the women in their lives, actively reporting cases of gender-based violence in their communities to the authorities or adolescent boys reducing the use of vulgar language at home.

Best Practices

To create a safe space for men to feel comfortable with talking about issues of gender-based violence and sharing their stories, Peter does a few things:

Invite men to explore how they learnt to act this way

Many actions the men take are deeply rooted in the culture they grew up in. Instead of telling the men what they are doing is wrong, the facilitator invites the men to explore the beliefs that led to their actions. Only after this exploration is complete does Peter invite a professional to correct some misconceptions the men may have.

For example, family planning has been a very sensitive issue whenever it is discussed during the sessions. In Zambia, most men prefer to have sons because of a cultural myth that men with only daughters are impotent and weak; which is a big knock on their pride.

This belief can lead men to take on hurtful actions such as engaging in an affair with another woman hoping she would bear him a son or accusing their wives of having a defect; which can destroy their families and escalate to gender-based violence.

During the sessions, the facilitator may ask the men to explore questions like:

- Where did you learn about this belief?

- Did anyone grow up with a father who acted this way?

- If yes, how did you feel?

- How do your wives feel about not being able to bear a son?

- What is the impact of your actions?

- Is this what you wish to create?

The facilitator and other participants adopt a mindset of curiosity rather than judgment, focusing on listening and empathizing with the man who is sharing. “It is not about feeding them information to convince them that this belief is wrong, but creating a space where they can feel safe to examine whether it is true that men who only have daughters are weak and whether the damage caused by this belief is something they can accept. This becomes a teachable moment for us,” said Peter.

Sometimes the conversations get heated as people are triggered by the sharing of others but Peter does not think that is bad as it means people are actively engaged and not passively detached. The onus is on the facilitator to remind participants of the rule of non-judgment and invite them to practice it.

He has found that when men are given this space of exploration, they are significantly more receptive to new information from a professional that may correct their misconception, such as a medical officer from the Ministry of Health who shares the science behind what leads to the conception of a boy and girl.

Even then, Peter does not attempt to change their mind. “Our approach is to lay out the facts and invite the men to decide for themselves. Ultimately, we cannot force them but we have found that as men become more aware of why they adopt these beliefs, the more likely they are to want to change them,” he added.

Share first to encourage other men to share

Sometimes, men struggle to share their challenges in the Boardroom because they feel ashamed. In situations like these, Peter and his facilitators share their personal experiences with the topic to get the ball rolling.

For example, Peter might talk about his experience responding to people who say he is a weak man because he has two daughters. “Being vulnerable by sharing first helps show the other men that the space is safe and we are not here to judge,” said Peter.

Give time for silence

While it is important to find ways to encourage men to share, it is also important to give time for silence for men to process the sharing given by other men in the Boardroom.

Just because people are silent does not mean they are not engaged. “They are likely to be thinking about how what was shared relates to their lives and this quiet time for introspection is crucial to them being receptive to changing their actions,” said Peter.

Involve trusted leaders in the sessions

Peter tries to bring on respected elders in the community such as village chiefs or religious leaders to either participate in the session or serve as facilitators. This helps encourage more men to attend and increases the quality of the sharing.

This is especially important in facilitating conversations with older men, who might be less comfortable participating in a conversation facilitated by a younger facilitator.

Limit the session to men of a similar age group or background

This increases the chances that they can relate to each other's challenges due to being in a similar age group. Similarities enable the men to quickly build familiarity that helps them trust each other to create a safe space for authentic sharing to happen.

“With the depth of sharing we want to achieve in the Men’s Boardroom, it is much easier to start off with a foundation of familiarity than if they were very different from each other,” said Peter. Typically, the Men’s Boardroom groups adolescents and young adults in one group and men above age 30 in another.

Protect the youth and yourself by developing a Code of Conduct

Peter developed a Code of Conduct which applies to all stakeholders (e.g. volunteers, facilitators, etc) of Men of Honor to protect the boys and men they work with. Some details in his Code of Conduct include operational guidelines such as ensuring a facilitator is not in a confined space with a youth and scenario-based guidelines such as how to handle youths who develop affectionate feelings towards volunteers, etc

Above all, volunteers and facilitators for Men of Honor commit to conduct themselves in a professional manner. While on duty, they are not allowed to consume alcohol, use swear words or engage in fights. They commit to seeing the potential of the boys and men and not just their problems.