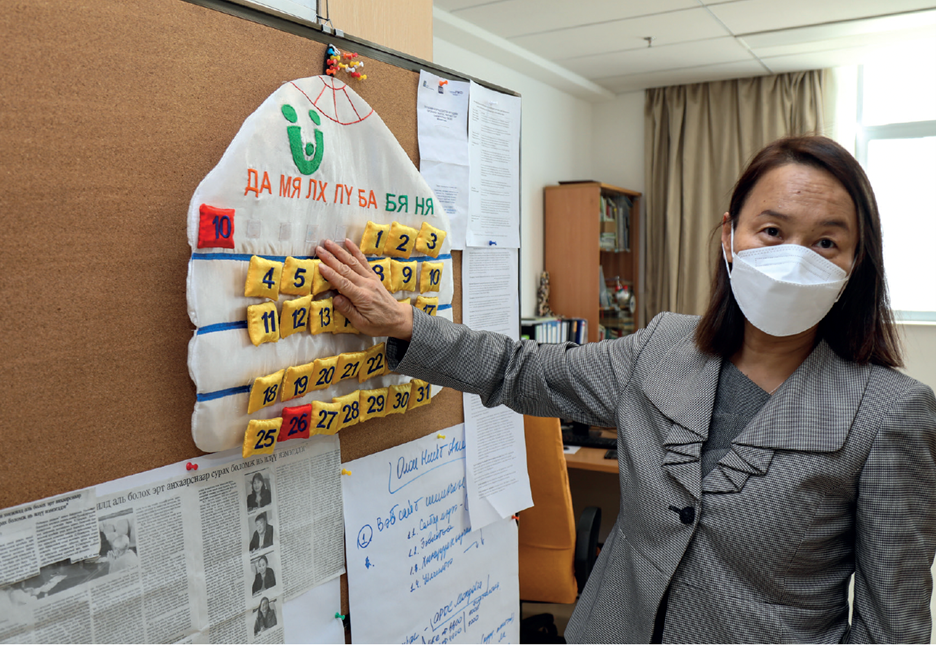

Inside a Mongolian childcare for children with special needs

Gerel started a childcare centre for children with special needs to receive education and provide respite their parents. Read more about the best practices she learned here.

Among Mongolia's 11,600 children with disabilities, 4,000 (34%) are unable to read and write. Despite the constitutional guarantee of free basic education for all citizens, many children with disabilities and special needs face challenges due to:

Insufficient infrastructure and trained teachers

Mongolia currently has six special education schools which reach full enrollment quickly, meaning that some children with disabilities or special needs may miss out.

Compounding the issue is a shortage of teachers and therapists specifically trained to work with students with developmental disabilities, because of a lack of funding. Affected children also find it difficult to attend mainstream schools because these schools often lack the necessary equipment and accessible facilities.

Some children stay at home, which becomes a big problem later on in life

This lack of trained teachers and overcrowded classrooms leads some parents to send their child to private care centers or hire private tutors to give individual lessons. However, for families unable to afford these options, keeping their children at home becomes the only choice.

This deprives their children of the chance to socialize and practice living life as an active person. "Getting an education is not just about gaining knowledge but also learning about how to navigate life in society. If they stay at home, they lose the chance to learn how to be more self-sufficient and independent. What will happen to them when their caregiver is gone?” Gerel said.

There aren’t many support groups for parents in Mongolia

Upon learning of their child’s disability or special needs, parents often experience a spectrum of emotions from disbelief to grief. Some might even be in denial, which leads them to procrastinate in looking for therapy, causing their child to lose vital time in early brain development.

Compounding the issue is that support groups for parents of children with special needs are rare, with one of the few organizations serving this purpose being the Association of Parents with Differently-abled Children (APDC) which has 20 branches across Mongolia including 16 in the countryside.

Unlike countries like the United States where support groups or seeking help from a psychologist for alcoholism, trauma, mental health, etc are common, this culture is not present in Mongolia. Parents are often under a lot of stress with few avenues for relief.

Gerel's journey advocating for children with special needs started because of her son

She started the “Narkhanii Ineemseglel” child development center because of her experiences with her first son, who was born in 2015. Stricken with a high fever just days after his birth, he was eventually diagnosed with Kernicterus, a rare condition caused by excessive bilirubin in the blood, leading to jaundice.

At the time, hospitals in Mongolia did not have sufficient phototherapy machines which could reduce her son’s bilirubin levels. By the time Gerel brought her son to a top neurologist in Beijing, China, her son had suffered permanent brain damage, which led to a further diagnosis of cerebral palsy.

Like many parents of children with special needs, she went through an emotional rollercoaster.

“When the doctor made his diagnosis, I was shocked and did not want to believe that my child had this condition. The first few months were very overwhelming, as I struggled to accept that my family’s life would be changed forever,” said Gerel.

Shock gave way to grief, as she mourned the loss of the ‘normal’ life she had anticipated for her son. Thinking about the future and the challenges ahead for her son’s health and development filled her with anxiety and fear. “I also struggled with self-blame - could I have prevented my son’s condition?” she added.

After nearly a year of grappling with her child's condition, Gerel sought therapy services for him in Sweden in 2016, where he responded positively to various physical, occupational and behavioral therapies over two months. Unable to stay long-term due to citizenship constraints, she returned to Mongolia and discovered a care center started by one of the country's first physical therapists.

“Bringing my son to the center was a big mental relief for me after taking care of him 24/7 for almost 2 years. It gave me some semblance of a normal life,” said Gerel.

When the center faced closure in 2019 due to funding shortages, many parents called Gerel in tears, afraid that they could soon lose the mental relief and support provided by the care center.

Dirven by a sense of duty to her son and others, Gerel decided to establish a care center. Using her limited savings, she purchased an apartment and personally oversaw the interior design and renovations. "It was a very sudden decision but I knew I had to continue the work of that therapist so my son and other children can have a safe place to go," she said.

Despite facing many adversities along the way, including the tragic loss of her son to sudden cardiac arrest in 2021, Gerel remains steadfast in her commitment to supporting families and providing essential care for children with special needs.

Solution: A day care center for children with special needs

Currently, the center provides care for fifteen children, aged 2 to 12, with special needs like Cerebral Palsy, Down Syndrome and Autism. Most children have severe physical conditions and don't have full control over their body.

The center's main objective is to enhance their psychomotor skills and prepare them for potential enrollment in government or mainstream special needs schools.

A typical day at the center starts with the carer feeding children individually. As this happens, the other children undergo daily physical therapy sessions, sometimes using a standing frame with different positions to stimulate muscle movements.

Exercises like head control and rolling are used to promote the right muscle growth and address muscle development issues resulting from the children's bodies being in the wrong shape for a prolonged time.

A speech therapist and pediatrician visit twice a week to conduct speech therapy and medical checkups. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the center used to offer hydrotherapy sessions, which has several benefits for children with special needs, such as enhancing muscle strength through low-impact exercises performed in water. Occasionally, a masseuse would come in to massage each child after each hydrotherapy session.

Gerel is continually thinking of new ways to improve the facilities and equipment at the care centre to enrich the children's experiences, such as providing for more chairs and standing frames in anticipation of more students in the future.

By providing full-day care, the center offers parents or caregivers some respite, allowing them to have some semblance of a ‘normal’ life, such as going to work or taking a vacation. Extra services, such as extended pickup hours and weekend care, are also available to further alleviate parental stress.

Impact measurement

For Gerel, success for the center is primarily about keeping the center open. "The work is very hard, especially when we are a non-profit. Just surviving is a huge success," she said.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were significant physical improvements amongst the children. Some who could only crawl on their chest previously had progressed to using their knees and hands to sit up. They even had two children who could move on from the center into a government school.

However, the closure of the center due to COVID-19 restrictions led some children to regress when they stayed at home, erasing much of the progress that was made.

“Ideally success would mean tracking metrics such as the number of children successfully transitioning to schools, reflecting the effectiveness of the therapy provided," said Gerel.

She has also observed a reduction in parental stress and increased capacity to care for their children at home, because they were able to leave their children at the center. These are positive outcomes that contribute to family well-being and stability.

Best Practices

Hire staff who are passionate about working with children with special needs

This is a critical part of what makes the centre work. Gerel believes in selecting staff (and volunteers) who have demonstrated patience and a passion for working with children with special needs, even if they may not have the relevant educational qualifications.

While the center's main carer is not a specialist with a diploma in working with special needs children, she has an intrinsic interest in the children and practical experience in how to handle situations like feeding time, which makes a world of difference.

This intrinsic motivation and passion leads them to do small things that create a positive learning space where children feel safe. For example:

- They welcome the children personally when they arrive at the centre, calling their names to acknowledge their arrival and paying them a compliment.

- They creatively involve children in art activities, even those with Cerebral Palsy who have challenges with psychomotor skills. It could be as simple as making sure the child touches the paper or dips their paint brush into the watercolors.

- They make an effort to learn the tendencies of each child they work with and understand what they are trying to communicate. After seeing the children every weekday for almost two years, the center's main carer can tell what a child needs just by what they are showing on their face or a particular sound they make.

Setup mechanisms to ensure safety of the children

Gerel ensures all equipment within the day care center is child-proofed. For example, placing furniture strategically to cover power sockets, installing thick rubber flooring and sticking soft bumpers around the walls to minimize injury risks. The main carer remains vigilant for potential hazards like choking or bedsores, taking prompt action when necessary.

While Gerel aims to implement surveillance cameras for added security, she currently relies on constant communication between the main carer and parent to assure them that their child is being well taken care of and there is no abuse at the center.

Daily updates are provided to parents upon pickup about their child's activities, behavior, diet and overall mood during the day. If there are medical conditions like a fever, parents would be notified immediately.

“Seeing their child feeling happy to come to the center is another assurance to parents that they are being well taken care of. Otherwise, they will cry and not want to come,” said Gerel.

Find an optimal carer to child ratio based on the needs of children you are working with

Another reason for the center's success is that it has found an optimal carer to child ratio (1 carer to 2 children at the moment). An optimal ratio will depend on the needs of the children you are caring for, and a good example of this is feeding. For example, a child with a more severe form of cerebral palsy might take up to 1 hour to eat whereas another child with Down Syndrome may take just 15 minutes.

Gerel emphasizes the importance of maintaining a balanced ratio to prveent extended wait times for feeding and ensure each child receives adequate attention.

In contrast, at other childcare centers where the carer to child ratio is too large, carers might not be able to give specialized attention to each child, as the other children might start screaming or making a mess when they are hungry.

“They don’t have time to cater to the eating habits of each child and often what happens is that the child does not eat as much as they should, resulting in compromised nutrition and weight loss,” said Gerel.

Train parents to ensure continuity of care beyond the centre

Although the children spend a lot of time at the centre on weekdays, their progress could be hindered if there is no continuity of care on the weekends when they are home. Once a month, the centre organizes a Parents’ Day, where parents come and learn from a special guest on various topics on how to care for their child.

These topics range from how to clean their child’s teeth to how to stimulate their child’s core muscles and facilitate basic physical activity for their muscles. This is done to ensure that the child’s development continues at home. “We could do a lot in the centre on the weekdays but if they do nothing on the weekends, the child will go backwards,” said Gerel.

The teamwork between parents and the carers and therapists at the centre ensures that quality care continues at home and helps the child to make slow and steady progress. Even if children have to miss a week at the centre because of illness, their parents will still know what to do to ensure their continued development.

Build a community of support to deal with burnout

Working with special needs children presents unique challenges and the center prioritizes measures to prevent burnout among staff, volunteers and parents.

Gerel keeps her carers motivated by enabling them to keep any revenue generated from after-hours care, such as when a parent leaves their child at the centre overnight.

“By working with us, they can earn more money to take care of her family while we get dedicated carers. It is a win-win situation for now,” said Gerel.

She also personally befriends the parents of each child and occasionally organizes meetings to bring them together to talk about their feelings and issues they may face. At these meetings, they can help each other to come up with solutions or share resources. These meetings are extremely helpful for parents who are having a special needs child for the first time.

“Many of them may take years of grieving to accept their child’s diagnosis but the first 3 years are the most important time of a child’s development. So the purpose of these meetings are to help them realize they are not alone and support them to move on as fast as possible to ensure the best care for their child,” said Gerel.

She has found that the best way to help parents escape burnout is to keep the centre open, so they can deposit their children and take a break for as long as possible. In fact, she has allowed parents to leave their children overnight at the centre with the carer, even once allowing a parent to leave their child at the centre for two weeks so they could go on a holiday.

Gerel's main challenge is to attract good therapists

While Gerel would love to scale the center to help more children, the primary challenge she faces is the difficulties with attracting good therapists to work at the center full time.

Hiring good therapists means being able to offer them a good salary because working with children with disabilities and special needs can be very tough. However, this means that she would have to charge fees higher than the current $290 USD monthly fee they are charging per child, which some parents might not be able to afford.

Furthermore, good therapists in Mongolia typically want to work abroad or at care centers much larger than the one that Gerel founded. Even with the lure of a good salary, it is still difficult to attract talent. Therefore, she gets by with part-time therapists who come to the center when they have breaks in their full time work.

She also takes on other income projects to grow the center's financial resources, so she can provide subsidized fees for parents in the event they do find a full-time therapist.

She dreams of a day where education can be inclusive of children with all needs

A while ago, Gerel read an article about a gentleman experiencing disabilities who went to college in Mongolia and Switzerland.

In Mongolia, his parents had to be responsible for bringing him up to the fourth floor for his classes and ensuring he understood the material. Whereas in Switzerland, the school adjusted lesson times and even built infrastructure to make the environment more inclusive for him.

“In Mongolia, he had to adjust to the conditions but in Switzerland, they adjusted the conditions for him to feel more included and comfortable,” noted Gerel.

She dreams of a day where there are policies, sufficient trained teachers and more funding to support the inclusion of children with disabilities or special needs in the education system.

Beyond having more special education schools, every school in Mongolia would have accessible buildings and where children with disabilities and special needs can be integrated into mainstream schools through the help of staff with capabilities in various forms of therapy.

“They are not separated from children of a similar age and over time, they feel a part of society and social acceptance is easier. Depending on the material taught, they might even study in the same classroom for some lessons. That day, we will no longer have special schools. Just schools,” she said.

She also dreams of the centre evolving to become a training centre for families - a place where children can come with their parents, siblings and grandparents. As children undergo therapy, their family members receive training on how to care for them at home and psychological support to help them accept their new role as caregivers of a child with special needs.

“I want this to be a place they can run to, not escape from,” said Gerel.

Please share them with us in the comments section below - we'd love to learn from you!