The holistic leadership development program transforming female refugees into changemakers

Through a holistic leadership development program comprising modules around identity, migration, power, problem solving, etc, The Azalea Initiative transforms female refugees into changemakers

While working for Suka Society, a non-profit organization that protects and develops children from marginalized communities in Malaysia, Wong Chen Li (Chen) got to interact with three young refugee women who were 19 years old and nearing completion of their education at a local community school.

When asked to talk about their aspirations after graduation, one of the women said: “There is really nothing else for me. My community wants me to get married then stay at home to be a housewife. What is there to look forward to in my life except for potentially resettling in a new country?”

This encounter deeply impacted Chen. Just like any young person her age, the woman was thinking about her future and asking what is next. But unlike other young women in Malaysia, she did not have many options.

As of December 2023, there are some 185,300 refugees and asylum seekers registered with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in Malaysia. They come from all around the world, Myanmar, Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Pakistan, etc, fleeing war, persecution or abuse.

Among them, 63,000 are women (34%) and 51,639 are children below the age of 18 (27%). These figures exclude a significant number of undocumented refugees.

There is a lack of development opportunities for refugee women

Upon finishing their studies at local community schools operated by NGOs at age 18, most refugee girls and young women face limited prospects. Many come from communities with patriarchal values who see women as homemakers and subservient to men. Therefore, they may become resigned to a life of staying at home.

They also often experience restrictions such as being unable to go outside without a man accompanying them; or even verbal abuse and sexual violence. Despite these challenges, Chen has encountered many refugee women with aspirations to learn skills, be confident and contribute towards improving the quality of life in their communities.

This is reinforced by systemic barriers

While there are some development opportunities, refugee women face several difficulties in accessing them. Many lack proficiency in English which hinders their participation in these programs. Some lack money to take public transportation, are afraid of being detained by the police or are overwhelmed with caregiving duties at home to carve out time for their self-growth.

While there are some negative perceptions towards refugees, Malaysia is also seeing an increase in refugees who step up to be changemakers for their communities, providing much needed food assistance or interpretation services when communicating with government agencies.

For example, Rofique, an 18-year old Rohingya refugee, coordinated with different NGOs to provide food assistance to over 200 families during the COVID-19 lockdown in Malaysia.

“How could we have leadership programs that develop the skills and strengths of refugees to address problems in their community?” Chen wondered.

Solution: The Azalea Initiative

A broad overview

The Azalea Initiative is a year-long women’s leadership development program organized by the Akar Umbi Development Society that aims to empower women of marginalized identities aged 18 - 35 years old to become changemakers for their communities.

The program has run for 3 cohorts of 12 - 15 refugee women, each of different ethnicities and countries. Over the years, the program has been refined to include the following components:

- 2 months - a selection process comprising questionnaires and interviews with the Azalea Initiative team to assess if they are a good fit for the program

- 4 months - selected women participate in workshops taught by different trainers covering 8 modules (two modules per month) around topics such as identity, migration, power, resilience, justice, solidarity, community organizing, leadership and problem solving.

- 6 months - the women apply the skills learnt during the workshops by implementing their impact project, while being mentored by staff and volunteers from the Azalea Initiative.

- 5 sessions throughout the program - participants get access to mentors who they can work with on personal and community leadership

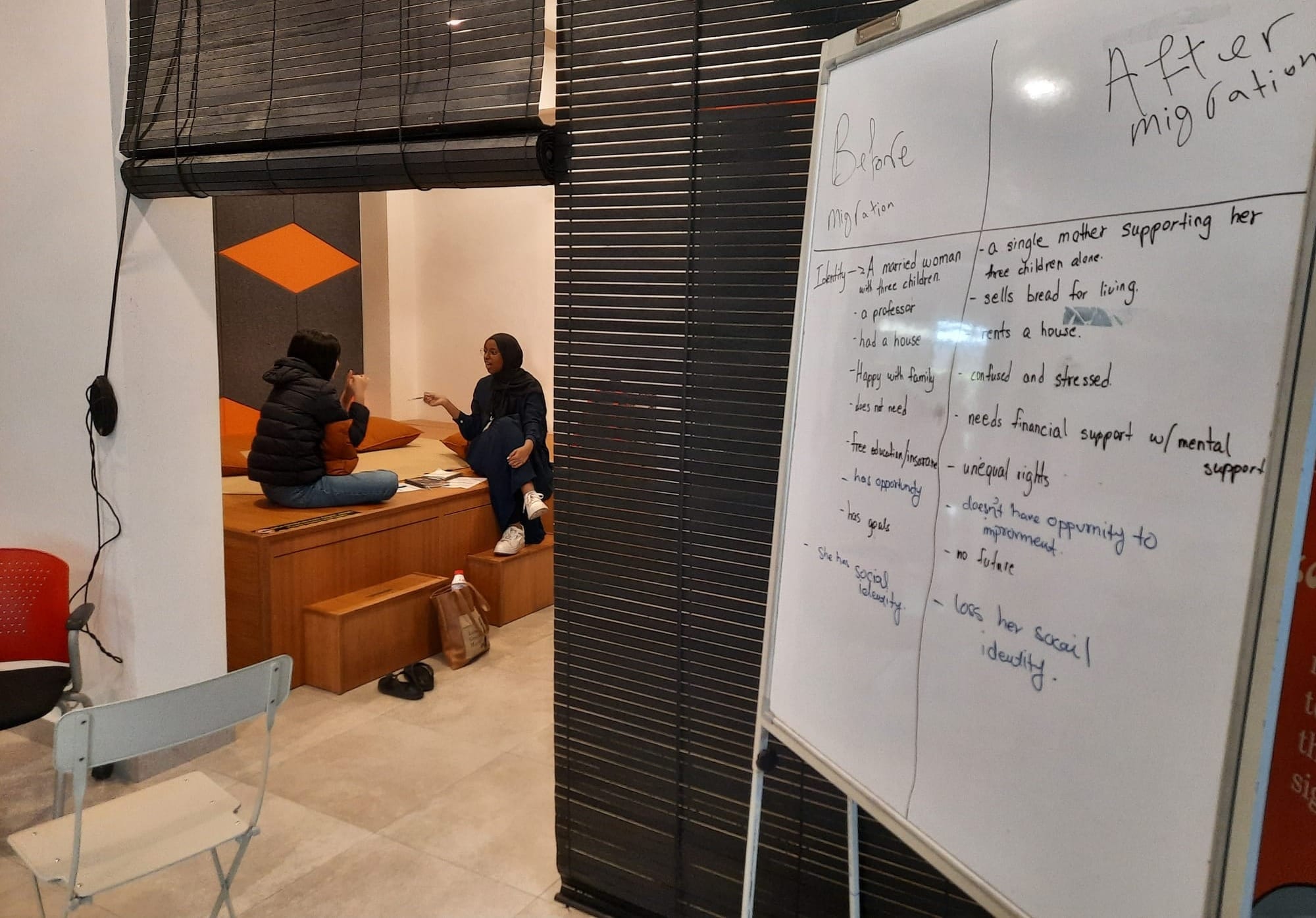

The initial modules of the program center on helping women to explore who they are, what they perceive their identity to be and how migration has affected their identity.

Some women might believe that because they have migrated to a new country and don’t speak the language, their skills and previous experiences matter less. While others may have lived under patriarchal values all their lives and believe that their place is at home and not developing themselves.

“Uncovering and addressing these limiting beliefs is crucial to empower them to envision themselves as changemakers. Without this mindset shift, their motivation and engagement in the program may suffer,” said Chen.

Subsequent modules equip women with the skills needed to navigate the world of funders and grantors, preparing them to craft effective grant applications for their projects. They also dive into understanding various forms of power, identifying forms of power that they or their communities have and explore strategies to access forms of power they do not have.

The women also spend time analyzing issues within their communities and brainstorming for an impact project they can create to benefit their communities.

Participants in the Azalea Initiative spend significant time talking to each other and making sense of the concepts. “Leadership is a practical skill and we help the women to practice it during the session,” Chen said.

The structure for each module

Each module spans 6 - 8 hours (an entire day) and has the following elements:

- Transition - each workshop starts with breakfast and a 10 minute ‘thinking time’ segment where participants find a partner and talk about whatever is on their mind (e.g. their cat went missing and they feel very worried) without interruption for 3 minutes and then switch over. They complete the segment by spending the last 4 minutes talking to each other.

This enables participants to unburden themselves before the program begins. “We ask them to imagine packing their troubles into a bag and leaving it at the door, which they can pick up later if they want, so they can focus on themselves for the next 8 hours,” said Chen.

- Interactive Activity - Chen has found that lecture-style workshops don’t work too well, especially for sessions that happen after lunch. Instead, she weaves in interactive activities to help participants understand the concepts, using tools like small group discussions, art and theater-based exercises.

- Reflection - workshops end with participants reflecting on how the topic covered was relevant to their lives, using questions such as “what did you discover about yourself today?” Or “was there anything that made you feel uncomfortable?”

At the end of the program, the women receive a leadership report - a compilation of their answers to this reflection segment at the end of each module - that serves as a record of their personal growth during the program.

Impact Measurement

The Azalea Initiative measures the following 5 components using 16 questions to assess if the program has created a positive impact on participants.

- Access to opportunities - is it convenient and easy for participants to attend the program?

- Personal development - are participants able to develop their confidence and leadership skills?

- Building support systems - are participants able to find friends or peers who can support them?

- Psychological safety - do participants feel safe to engage with program material and express themselves?

- Community building - do participants feel equipped to create something that benefits their communities?

Chen conducts three surveys throughout the program: pre-program, mid-program and post-program. The midpoint evaluation is particularly valuable for adjusting program elements based on participant feedback.

For example, during Cohort 3, the survey revealed that two participants faced challenges with public transportation. In response, the Program Coordinator arranged private-hire cars for them, enabling them to continue participating and eventually successfully completing the program.

Another insight uncovered was that participants wanted more opportunities to network with people working in Foundations and Grantors. Therefore, Chen identified a networking event organized by the Asian Venture Philanthropy Network (AVPN), where the women presented the Azalea Initiative and connected representatives from various sectors, including the Gates Foundation.

In designing survey questions, Chen opts for descriptive language over numbered scales. For example, instead of rating improvement in confidence on a scale of 1 to 7, participants select statements like "no improvement", "very little improvement", "some improvement", or "significant improvement", which enables Chen to glean clearer insights into their experiences and perceptions.

Best Practices

Select people who fit the criteria of the program

Selecting the right people whose values and aspirations align with the program is key to the success of the Azalea Initiative. Application typically opens for a month, with Chen and her team conducting a pre-selection interview. Some questions they ask include:

- Where do you live? If you take public transport, how long would it take you to reach the venue for the workshops?

- How comfortable are you with taking public transport? How comfortable are you with taking private-hire cars like taxis or Grab?

- Do you have dependents you cannot leave behind to participate in a workshop?

- If you meet a participant of a different ethnicity who has a history of conflict with you (e.g. Pashtun and Hazara), what would you do?

- If you receive a grant, what would you want to do with our community?

- What is your goal for yourself in participating in the program?

These questions help Chen and her team to assess the motivations of participants and their likelihood of following through with the program.

How to create a psychologically safe space

Many of the women who participate have experienced traumatic events in their lives. One thing the Azalea Initiative does especially well is creating a psychologically safe space that enables participants to gain deeper self-awareness and create meaningful life transformations.

“We want coming to Azaela to feel like coming home. And this sense of home is not created by just me, but by participants who start to see each other as part of a family,” said Chen.

A few factors contribute to this:

- Ask for consent and practice setting boundaries - the first module starts with a consent briefing, where the women are given a detailed consent form. Unlike most forms which lump consent into one question, Azalea’s form asks for the women’s consent in specific situations like being recorded in photos, videos, audio or for their written reflections or artwork to be shared.

They can also choose the extent to which they are comfortable being recorded, having options such as “partially seen”, “fully seen” and “do not want to be seen at all”.

While photos featuring faces are valuable for fundraising purposes, Chen intentionally diverges from this conventional approach. Consent given by participants can be retracted at any time.

For example, in a previous cohort, a participant requested that her photos be removed after a year. By actively giving consent, the women begin to discover and establish their boundaries, helping them feel safe and in control. - Notice anomalies but let the person decide what support she needs - Chen and her colleagues actively notice any anomalies in the behavior of participants, such as a participant who is usually extroverted suddenly being very quiet and withdrawing from conversations.

They let participants know that they are here to listen and offer support at any time if they choose to. “If they don’t feel like telling me, they don't have to tell me. They can talk to a fellow participant or keep to themselves,” she said.

- Create separation from immediate stressors - participants can leave the room at any time if they feel overwhelmed. They don’t have to ask for permission and the facilitators are trained to continue on without interruption, so that nobody feels shy or ashamed for doing so.

Sometimes Chen asks them if they’d like to try a breathing exercise just to feel and release any stressors they have, before going back to the program. The transition activity mentioned above also invites participants to drop burdens they may be carrying at the door, so they can be fully present in the program.

The program always ends with some breathing activities, to help participants mindfully pick up those burdens again, if they choose to. - Help them to build a support system - the program provides participants with a budget to access mental health services if needed. In addition to professional support, Chen and her team assist participants with identifying people in their immediate circles they can turn to for help.

Sometimes, it might not even need to be someone who is alive. “If their late grandma was their biggest source of support, we help them see how the legacy she left behind can be a support for them,” said Chen. - Respect confidentiality - everything that is shared in the room during the workshops is assumed to be kept confidential unless the participant gives permission for it to be shared.

- Appreciate rather than punish - Chen and her team prioritize empathy for the circumstances the women are in over punishment. For example, some women have a tendency to be late for the program.

Although Chen has to remind them multiple times, she is mindful that they are affected by transportation delays beyond their control. “We practice being kind in the way we talk to them, even when frustrations may occur,” she said.

Even if the women decide to drop out halfway during the program by choice or circumstance, Chen and her colleagues always leave the door open for them to come back.

“It might not look good on our impact numbers but the women are more than numbers to me and we show it by honoring their decisions. We go as far as they are willing to go with us,” she said.

Take care of surrounding issues that might affect their participation

The Azalea Initiative differs from similar programs in Malaysia by addressing practical barriers that may hinder the women's ability to participate. For example, it funds transportation costs that the women incur to participate in the program, whether through public transport or through private-hire cars.

This cost takes up a significant amount in the budget and Chen is often questioned by stakeholders who believe that if the women are committed to their growth, they will find a way to make it to the program and want to reduce the costs for transportation.

“I believe their time should be as important as mine. If I find it difficult to spend two hours on a train to go to a workshop, then I should not place this expectation on them,” said Chen.

Rather than prescribing fixed amounts, she adopts a flexible reimbursement approach based on the transportation they use, so those who live nearer to public transport can choose to share the funds with those who live in more rural areas and require private-hire cars that cost more.

“We explain the situation and vest them with the responsibility for ensuring that each participant has adequate transport to reach the program venue. Understanding each other’s circumstances and finding ways to help builds a sense of community,” she said.

This also leads to outcomes such as a lower transportation cost and high punctuality rates.

Use different modalities to facilitate learning

Chen uses various activities to cater to the different learning styles of her participants. Some examples include:

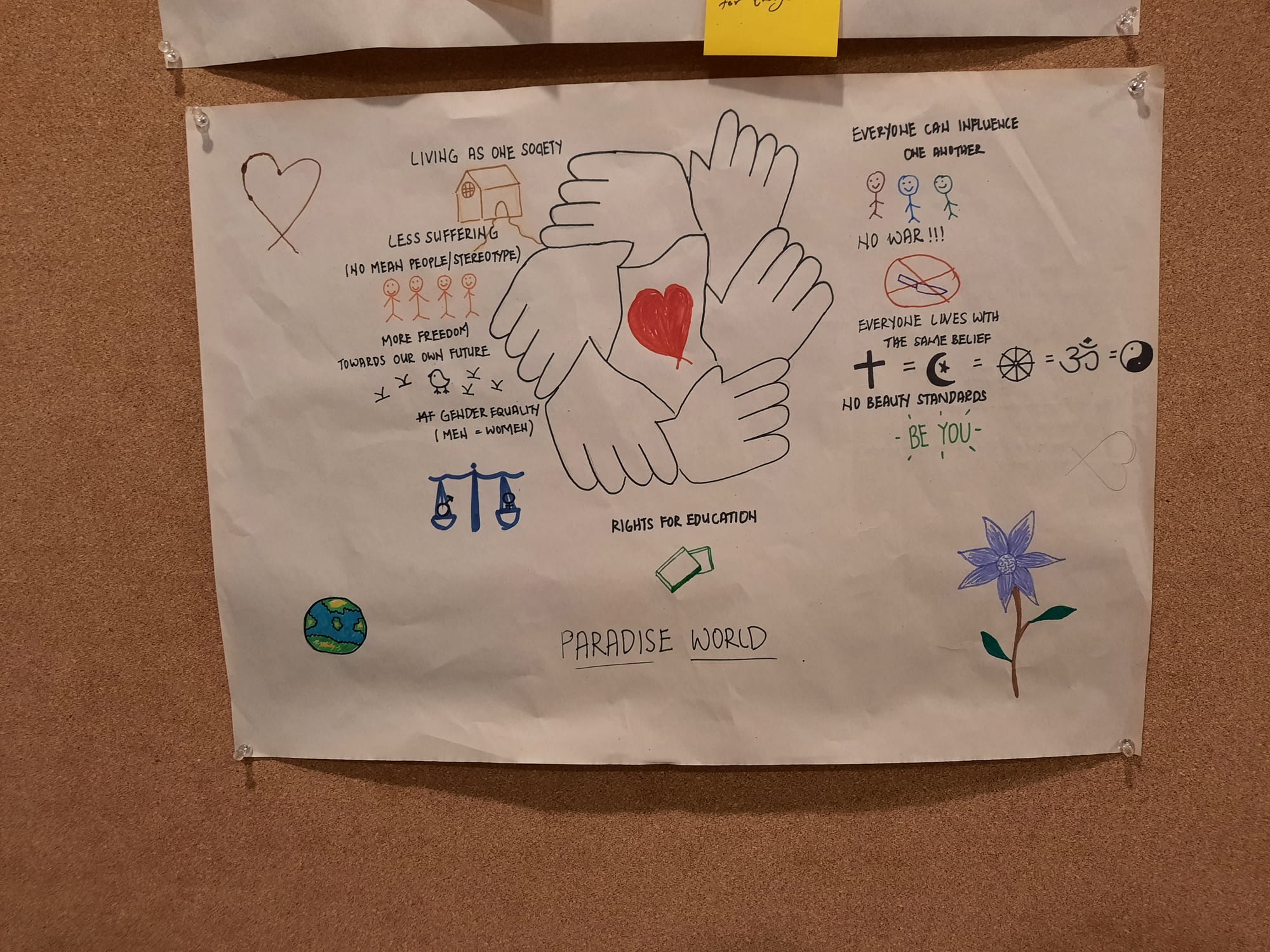

- During a discussion on stress, she invited a drama therapist to teach participants to identify stress points in their body and to express their emotions and release stress by practicing different body movements.

- During a session on leadership, participants were invited to draw a picture representing the leader they wanted to be. Some drew full portraits of themselves while others drew icons symbolizing each positive attribute which they wanted to embody.

- During a session on the topic of justice, participants were split into two groups. Within their groups, they were asked to share a story of an injustice that had happened to them or something they witnessed happening to another person. Each group selected one story to act out, with the other group tasked to figure out what was happening through guided questions from the facilitator. After that, the group acted out how they think the same injustice can be made right.

One participant shared how her father was killed by a hit and run driver and although she reported it to the police, they ruled it an accidental death. Reeling from the shock and sadness, she buried the incident deep within her and never spoke of it again until the activity.

Her group acted out a scene where bystanders went with her to make a police report and shared what they had witnessed, thereby enabling justice to be served to the perpetrator.

These tools help to break up the boredom of a lecture and enable participants to experience a range of tools which they can replicate in their own communities.

Beyond that, using different modalities also helps to make the sessions more inclusive for participants who prefer different forms of expression.

“Not everyone might be the best at expressing themselves through speaking. By drawing, acting or moving, we open up alternative ways to express what they see and how they feel. It becomes more personal,” said Chen.

Where possible, show, not tell

During one workshop, Chen and her colleagues realized that because of their different personalities, some participants spoke up more while others who were quieter were talked over and unable to express their views.

Instead of telling them that good leadership was about being inclusive of different voices in the room, they designed a game called Mr Robot for participants to discover this lesson for themselves.

In the game, participants are broken into smaller groups and given a task of building a robot using simple materials. Groups compete to build the robot in the shortest time and each person plays different roles:

- Leader - who can talk to other members of the group but they do not know what type of robot to build and cannot participate in building it

- Designer - A person who cannot talk and cannot build but is given crucial information on what type of robot to build

- Builder - A person who can build the robot but cannot talk and does not know what type of robot to build

Quieter participants are usually chosen to be the leader while those who tend to be more vocal are given roles where they cannot talk.

Participants who are vocal often feel frustrated by having to remain silent as they work through the task. Chen and her colleagues use this as a teachable moment to invite everyone to reflect on what was frustrating and how might leaders create inclusive spaces for those who are quiet but may have important insights to share their views.

“Emotion can be a very powerful teacher in helping the vocal ones understand what it feels like for people who are quiet. Where possible, we try to gamify our content to bring out these emotions and teachable moments,” said Chen.

Please share them with us in the comments section below - we'd love to learn from you!

Featured Changemaker

Wong Chen Li (Chen) is the Impact Driver at Akar Umbi Society, an organisation that collaborates with the grassroots communities towards ending marginalisation and creating equal opportunities. Prior to that, Chen served seven years as a Project Coordinator at SUKA Society focusing on building resilience in refugee and Orang Asli young people as well as peacebuilding programmes between refugees and Malaysian youths. Chen believes that the willingness to listen and create a conducive thinking environment in partnership with the grassroots communities are the keys to solving community issues. The grassroots themselves are an asset. She believes that the communities can thrive if time, opportunities, and resources are invested into building their people up.