What I Learned About Community Power in England

On a learning trip to England, I discovered how communities lead, co-own, and imagine. These are my reflections from IFS 100 and the Locality Conference.

Last month, I had the chance to spend time in the UK, first in London, for the 100-year anniversary of the International Federation of Settlements and Neighborhood Centres, and then in Liverpool for Locality’s annual convention.

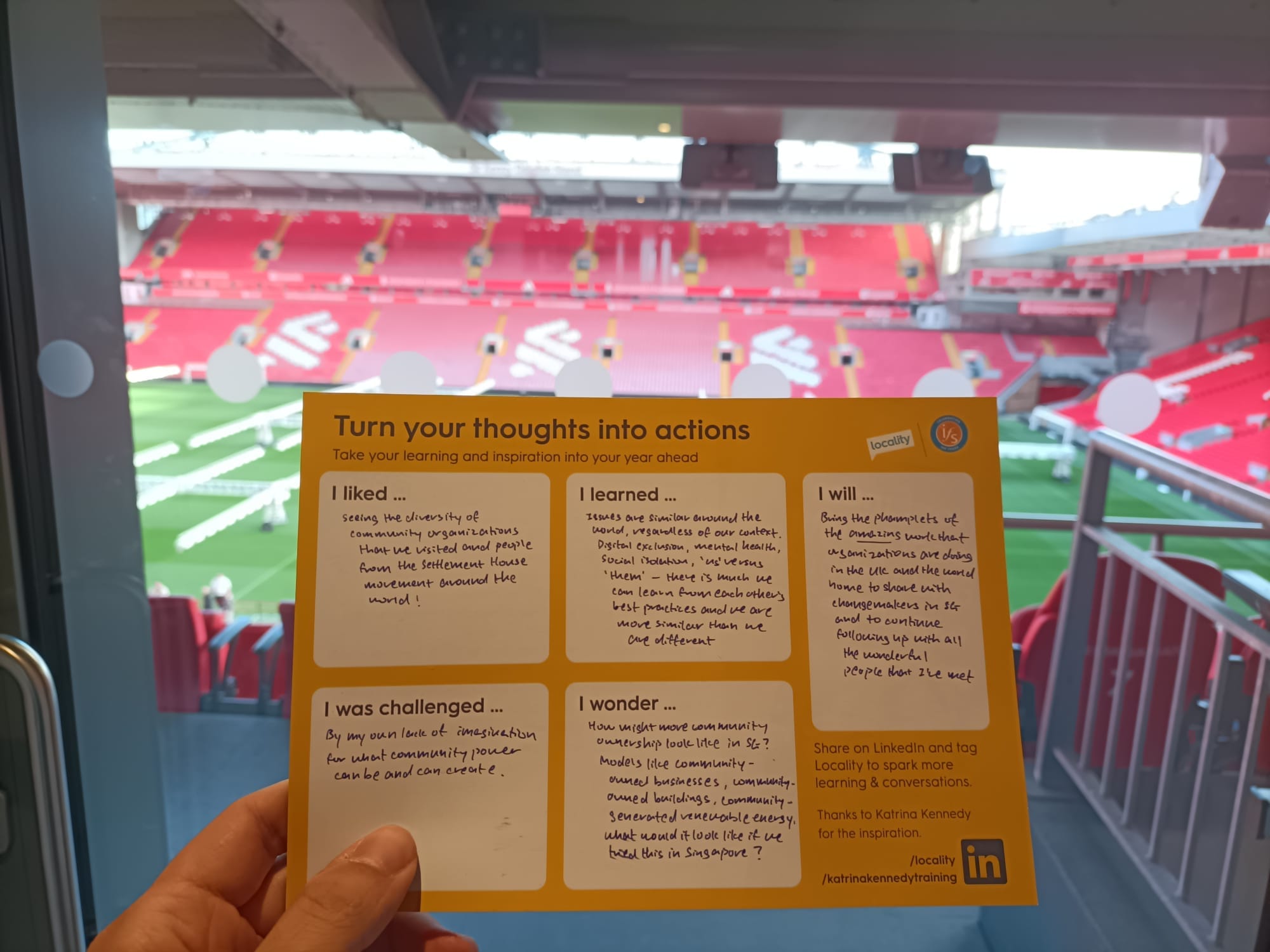

Across site visits, lightning talks, hallway chats, and panel discussions, I met community organizers, social workers and changemakers from all over the world. What surprised me most wasn't how different we were, but how similar.

Whether in Europe, North America or Singapore, many of us are grappling with the same issues: loneliness among seniors, rising youth mental health challenges, unemployment, the complexities of integrating migrants; to name a few.

Even the responses felt familiar: youth employment programs, day activities for older adults and support group programs for men's mental health.

But what stood out for me was how far community ownership has evolved in some parts of the UK. I saw models where communities don’t just participate in services. Instead, they own the spaces, run the services and shape their local economies.

As a lifelong Liverpool FC fan, sitting inside Anfield Stadium reflecting on all this felt surreal. Here are some of the reflections I carried home, many thanks to Christopher Hanway and the Jacob Riis Neighborhood Settlement for enabling me to come on this trip!

Formal and Informal Mechanisms for Community Ownership

I was struck by how the community-based organizations (or nonprofits) I visited or interacted with seem to be stepping into roles I've rarely seen in Singapore. Beyond organizing programs, they are:

- Developing and managing their own housing (Coin Street Neighbourhood Centre in London, UK)

- Running their own community centres (Het Wijkpaleis in Rotterdam, the Netherlands)

- Creating jobs for their neighbors through a community-owned cooperative (Coalville C.A.N in Coalville, Leicestershire, UK)

- Developing low-carbon or renewable energy initiatives to provide energy or jobs for their neighborhoods, supported by organizations like the Community Energy Go

I came to understand that this sits within a broader shift in the UK towards what they call devolution - a process of pushing power and decision-making away from central government and into the hands of local authorities and increasingly, communities themselves.

Policy Initiatives

Following the passing of the Localism Act in 2011, several policy mechanisms enable this, such as:

- Community Asset Transfer Scheme - which allows local councils to transfer public buildings or land, like old libraries, community halls or sports facilities, to community organizations, often at below-market rate. The idea is that local groups are sometimes better placed to breathe new life into these spaces and tailor them to local needs. But it's not automatic: the group has to show a viable plan and the council has to agree.

- Community Right to Bid - which allows communities to nominate certain places, like a village pub, shops or post office, as an "Asset of Community Value". If the owner tries to sell it, the community gets a legal pause of up to six months to organize a bid to buy the asset for community use. While it doesn't guarantee they'll succeed, this mechanism has enabled communities across England to save many beloved pubs, post offices, sports fields and other amenities from closure or private re-development, by allowing time to mount a "people's bid" to take them over.

- Community Right to Challenge - which gives community groups the right to formally express interest in running a public service, like a library or a community centre, if they believe they can do it better. It can trigger a competitive process where their proposal must be considered alongside other providers.

I found a really interesting guide that Locality created about the Asset Transfer Scheme and the Right to Bid and one from My Community explaining the Right to Challenge.

Inclusive Decision Making

Beyond these policy mechanisms, I also learned about the everyday practices of inclusive decision-making that community organizations in Europe and the US are putting into place, like electing residents or service users to sit on "Community Advisory Boards", where they help shape programs and priorities from the ground-up.

At Het Wijkpaleis, a community centre in Rotterdam, Working Board Member Marieke Hillen explained to me that they developed a “Social Return Questionnaire” - an 18-question survey based on their own Theory of Change.

It was sent out to neighbours and community members who had participated in activities at the centre throughout the year, and used to evaluate whether the makers and tenants renting space there were contributing meaningfully to its broader community-building goals and if they should continue.

I appreciated this accountability not just upwards to funders but outwards to the very people the space exists for. Yes, it sounds like the post-program surveys that nonprofits are often asked to administer but something felt different for me.

I think it was because this was more than data collection for learning. It was a feedback loop that gave the community actual influence.

Community-Based Financing Mechanisms

To raise funds for the eventual purchase of their building from the municipality, Wijkpaleis issued community bonds. Residents, neighbors and supporters could choose how much to lend and for how long. In return, they would receive an annual interest and eventually get their capital back.

What struck me wasn't just the financial mechanism but the spirit behind it. As someone who started a community-owned co-operative in Singapore that issued shares, I really appreciated how these community bonds were community ownership in the literal sense.

People were investing not just in a building, but in the continued life of a space they cared about. Many bondholders, I was told by Marieke, chose to donate their interest back to Wijkpaleis.

It made me wonder whether we might one day build community institutions that residents not only use or support, but help own.

What Do We Give Up in the Name of Efficiency?

Last year, I gave a talk on citizen participation at the Institute of Policy Studies' Future-Ready Society conference. One thing I shared was how similar our neighborhoods have started to look.

Most town centres now orbit around large shopping malls, anchored by the same chain stores that can withstand high rents. Even the stalls at hawker centres in different neighborhoods are increasingly similar.

In Yishun, where I grew up, I remember Northpoint when it still had small vendors and mom-and-pop shops, each with their own quirks and personalities. Today, it's become Northpoint City - a sleek, sprawling mall dominated by big brands.

Can we still tell Bedok from Jurong?

Of course, every neighborhood has its nuances but I sometimes wonder if uniformity has outpaced identity.

I sense the same pattern unfolding in the social sector. Policies seem to encourage consolidation in areas like eldercare and preschools, favoring large anchor providers.

I can understand why. These are essential services and consolidating them under large providers likely makes quality control and regulatory oversight by government agencies more manageable.

This same tension between scaling / consolidation and staying local isn't unique to Singapore. When I visited Bede House, a community organization in Southwark, London that has served persons with disabilities in its neighborhood since 1938, I was struck by how intentionally they had chosen to stay small, despite pressure to expand into a bigger service hub.

Ultimately, I think this isn't a problem to be solved but perhaps, a polarity to be managed.

Big isn’t always better, and small isn’t always ideal but I think it's worth asking: what kind of balance are we settling into and is there room to shift towards more diversity in how places look, feel and function?

Community Ownership as an Alternative Logic

That's why community ownership like that at Wijkpaleis felt so compelling. At the Locality Convention, Jane Dawe, Director of Partnerships at Safe Regeneration in in Bootle, Liverpool, shared a similar story.

Her team transformed a vacant space into a vibrant community-owned pub called the Lock and Quay Community Pub, now co-owned by 300 local members, with all profits reinvested in the neighborhood. “It’s not a community centre,” she said, “it’s the centre of our community.”

On their website, a resident put it even more plainly: “It was just bricks. What they installed was pride.”

Communities Don't Lack Ambition; They Lack Permission

Jane’s keynote landed deeply with me. “Communities and community organizations don’t lack ambition,” she said. “They lack permission.” Why is that?

Because they’re often asked to solve long-term challenges with short-term grants. Because they’re locked in survival mode, renewing funding year after year. Because funders value compliance over connection, papers over people. “Regeneration without community power,” she added, “is not regeneration. It’s redevelopment.”

That line stayed with me. So did something Anna Clarke from the International Association for Community Development said to me in a quieter moment: that community development has been slowly de-politicized. “It’s taking the language, but not necessarily doing the work,” she said.

Many community-based organizations today are stuck delivering services through government contracts which ensures their financial survival, but in doing so, may be addressing symptoms rather than advocating against the root causes of social issues.

What Might We Build If We Had Permission?

It made me think: perhaps community ownership is one way we can bring distinctiveness and spirit back into our neighborhoods.

With rising property prices, the idea of owning anything physical beyond a HDB flat in Singapore, let alone a shared community space, feels far away. At least it does to me.

But if we want to nurture a national identity as Singaporeans beyond our race and religion, perhaps it starts with asking: what might be different if we allow residents the right to shape, to co-own and to co-imagine the future?

Ownership as a Path to Economic and Civic Empowerment

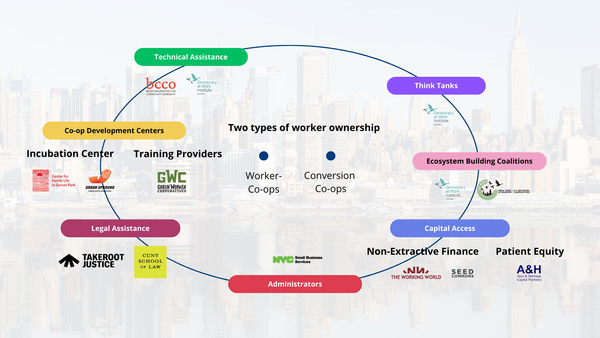

As I learnt during my time in New York City, community ownership of businesses and assets can be more than symbolic. It is a proven way to address issues like income inequality.

What if, instead of only providing financial assistance to low-income families, we helped them own a part of their local economy?

What might shift for them, not just materially but emotionally?

Because when neighbors co-own something, whether it's a building, a business or even a question about the future, something shifts, both in the place and the people who invest in it.

Ownership invites imagination and because people are different, the places we shape together will be too.