Why don't we have more co-ops in Singapore? An analysis of key issues by a local co-op founder

Co-ops are businesses that do good for society but why are there so few co-ops in Singapore and what can we do about it?

How I came to learn about cooperatives

Five years ago, I stumbled upon the cooperative model while helping to incorporate A Good Space (AGS), an organization aimed at uniting diverse changemakers to work together to create greater social impact.

Over the years, I saw this mission in action - whether it was disbursing $1.12 million in financial assistance, forming consortiums for high impact projects or bringing together 90+ multi-sector reps to develop innovative solutions for migrant workers in Singapore.

Back then, we sought a legal structure that best embodied our ideals of social impact, collaboration and shared ownership.

Then someone said: "Have you guys considered a cooperative?"

I, along with the 5 other founding members, had no idea what a cooperative was or how to run one. However, the concept of a changemaking entity owned by citizen changemakers - not by an institution, the government or any single person - resonated with me as an innovative idea worth pursuing.

After an arduous process (more on that later), A Good Space Co-operative Limited was officially incorporated on 31 March 2020, just days before the Circuit Breaker brought Singapore to a standstill.

What are co-ops?

As AGS' first General Manager, I started learning more about co-ops and the more I learnt, the more intrigued I became. In short, co-ops are member owned businesses that exist to benefit their members. In the case of AGS, the members are individual social changemakers.

Unlike traditional businesses that prioritize maximizing profit for investors or executives, co-ops aim to create social impact through its activities and ensure more equitable decision making and distribution of profits, amongst other unique features.

A video compiled by Cai Dewei, from the Institute of Policy Studies' Public Affairs Team, of the highlights from our Baltimore study trip, video credit: Institute of Policy Studies

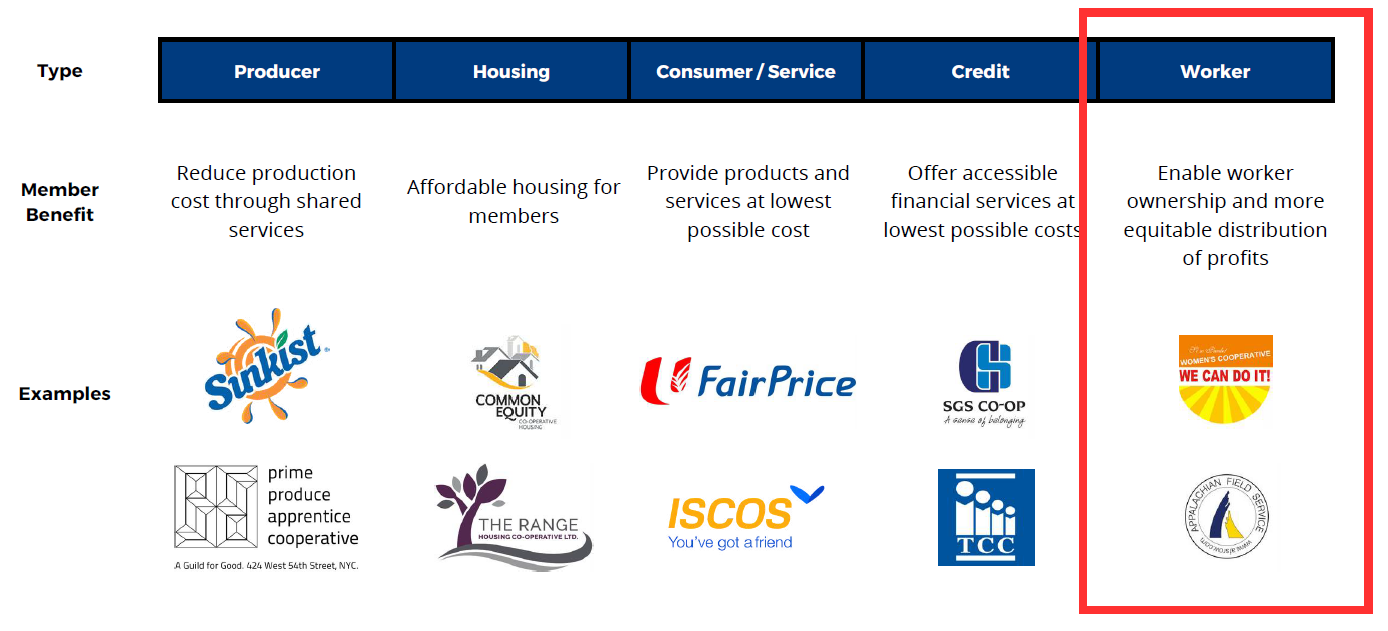

In Singapore, we primarily see consumer / service co-ops and credit co-ops, but co-ops can take many other forms, as illustrated in the table below. In 2022, during a study trip to Baltimore, Maryland in the United States with the Institute of Policy Studies, I discovered worker cooperatives - social enterprises with a further twist.

Rather than being owned by a founder who employs individuals from marginalized communities, worker co-ops are owned by these individuals themselves, who make decisions and share in the profits.

Could worker co-ops be another way to reduce economic inequality in Singapore?

This sparked my interest. While working with AGS, I learnt of various economic interventions aimed at uplifting low-income families in Singapore, such as the Progressive Wage Model, financial assistance, upskilling, job coaching and job placements.

Could enabling low-income community members to own businesses and make decisions be another way to reduce economic inequality and restore dignity?

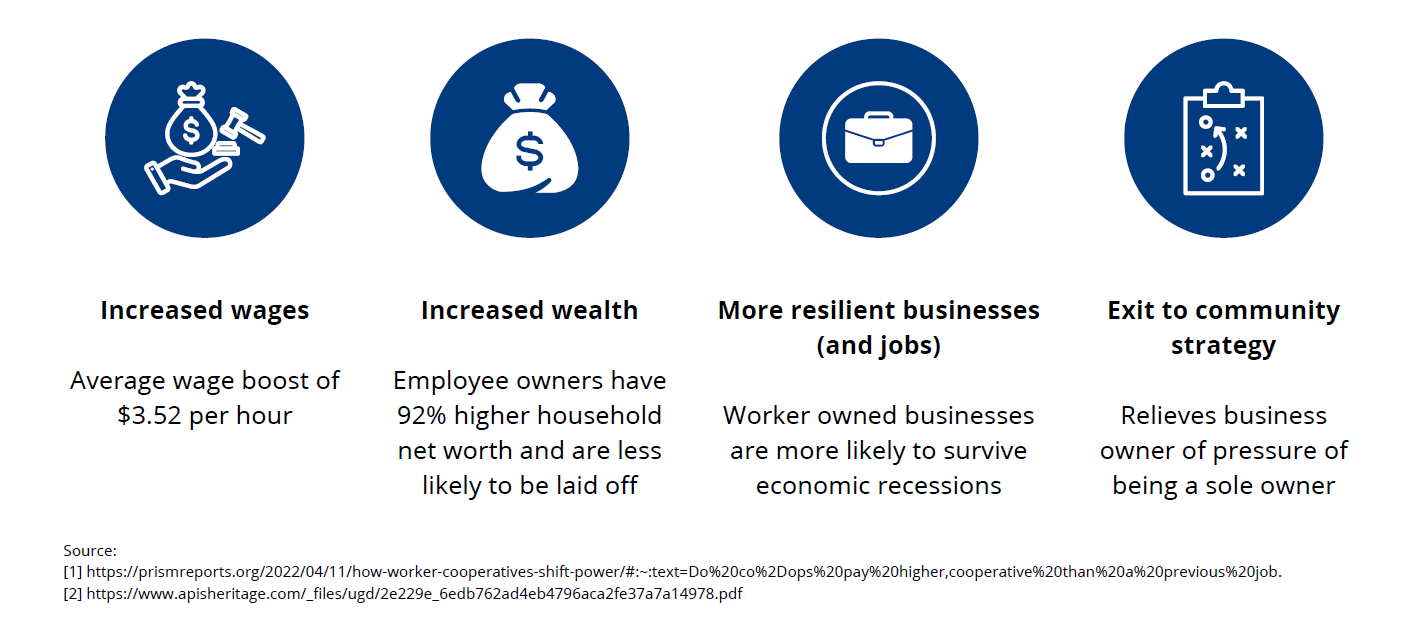

In fact, research from co-op think tanks in the United States has identified four key benefits of worker ownership:

A short history of co-ops in Singapore

Co-ops have existed in Singapore since 1925, with the first being the Singapore Municipal Employees' Co-operative Thrift and Loan Society Limited, a credit co-op established to provide loans and combat exorbitant interest rates charged by exploitative moneylenders.

Other credit co-ops emerged around the same time, offering loans to those who struggled to secure them from traditional banks due to a lack of collateral.

In this way, credit co-ops played a crucial role in promoting social and economic mobility, providing funds for people to start businesses or pursue their education. Later on, consumer / service co-ops like NTUC Fairprice and NTUC Income were started.

Fairprice helped to regulate the cost of necessities and prevent price gouging by merchants while Income provided insurance coverage to blue-collar workers, filling a gap left by insurers who were hesitant to cover them.

More recently during the COVID-19 pandemic, Fairprice played a crucial role in sourcing food items from suppliers around the world to ensure Singapore's food security.

The co-op movement in Singapore is stewarded by two organizations. The first is the Registry of Cooperative Societies (RCS), under the purview of the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY). It is responsible for governance and incorporation, similar to the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority's (ACRA) role for companies.

The second is the Singapore National Cooperative Federation (SNCF), which promotes the co-op movement and advocates for co-ops in Singapore. SNCF itself is also a co-op whose members are other co-ops like AGS. Its operational costs are supported by membership fees and funding from the Central Co-operative Fund.

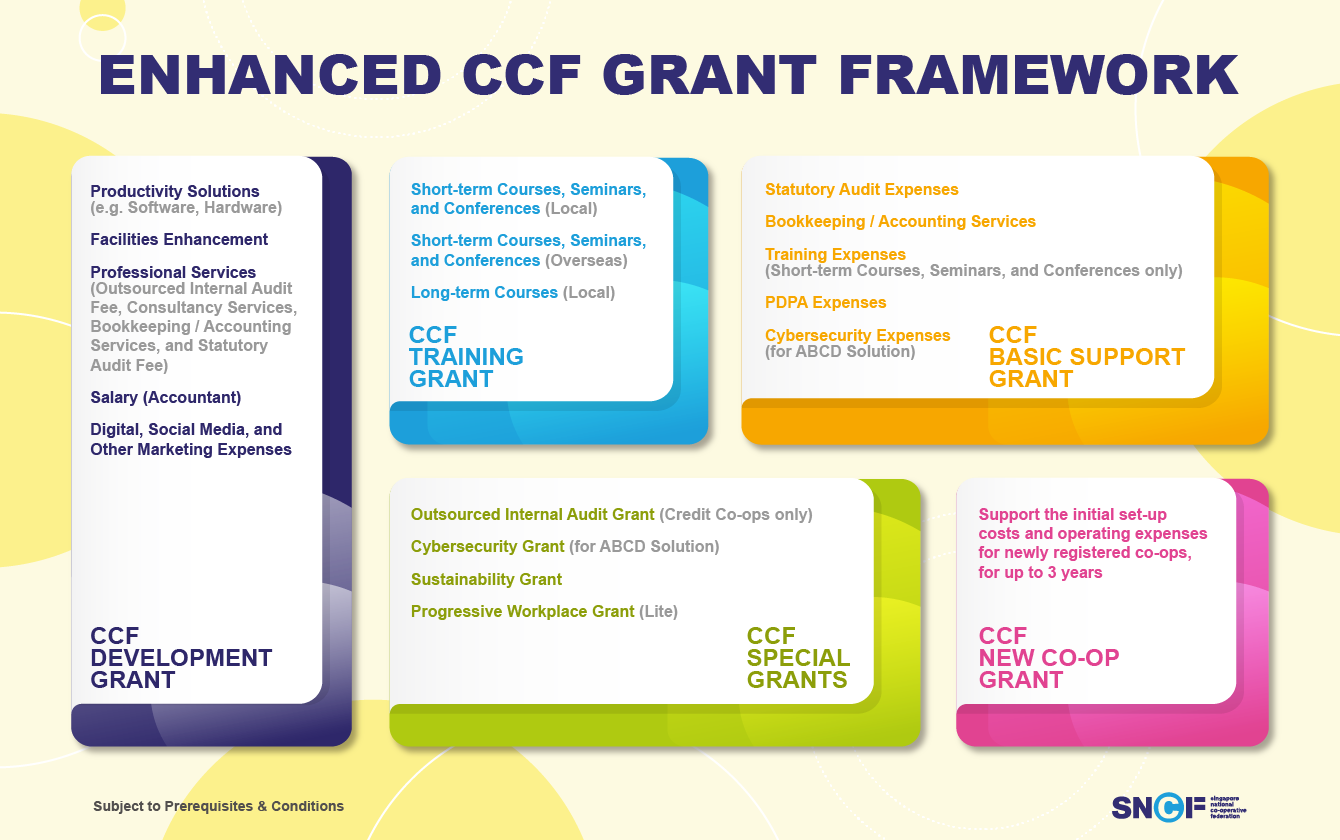

SNCF is also the Secretariat for the Central Cooperative Fund (CCF). It facilitates for co-ops to apply for the various grants under the CCF, such as grants for education, training, research, audits and in particular, a grant for new co-ops (more on that later).

Why aren't there more co-ops, or any worker co-ops, in Singapore?

To me, co-ops seem like a wonderful idea - a blend of doing business and doing good for society. Yet nearly 100 years after the first co-op was formed, there are only 79 co-ops in Singapore as of 2023, down from the 86 I remember when AGS was first incorporated in 2020.

In contrast, ACRA reports 592,343 corporate entities in Singapore as of March 2024 - almost 7,500 times more than the number of co-ops! To my knowledge, there are currently no worker co-ops in Singapore.

Although some co-op veterans told me that they remember some worker-owned co-ops in the past, I haven't been able to verify this from available records.

Why are there so few co-ops in Singapore?

And why are there currently no worker co-ops?

What can we do to create a thriving co-op ecosystem in Singapore?

All views presented here are my own, and not reflective of A Good Space Co-operative Limited. I am not an expert and don't have the answers, just directions of exploration.

So please don't shoot me lah.

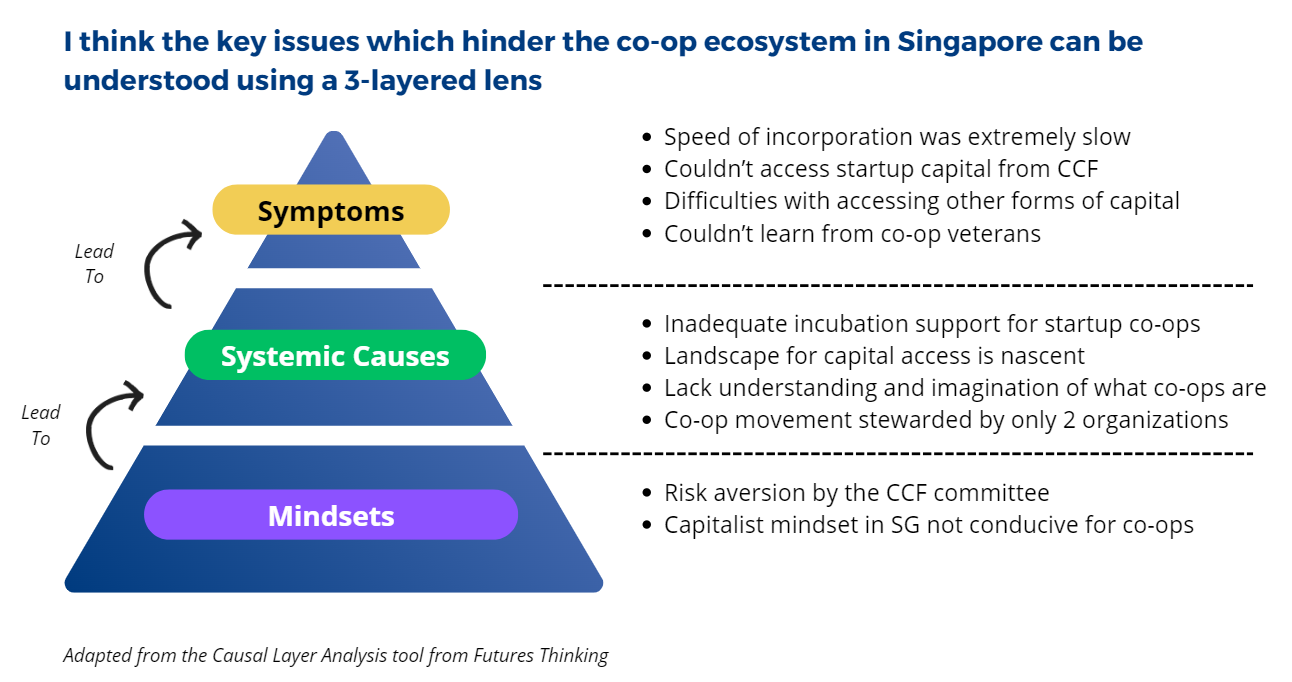

I believe the key issues hindering the co-op ecosystem in Singapore can be viewed through a three-layered lens. I'll explain these layers using my personal experiences in incorporating AGS and interacting with the broader co-op ecosystem as its first General Manager.

Symptoms: We faced 4 challenges in the early stages of incorporating AGS, which would likely be experienced by other startup co-ops

- The speed of incorporation was extremely slow - taking nearly nine months of back-and-forth with RCS. Our Relationship Managers from SNCF struggled to assist us with financial projections or business modelling, despite their good intentions.

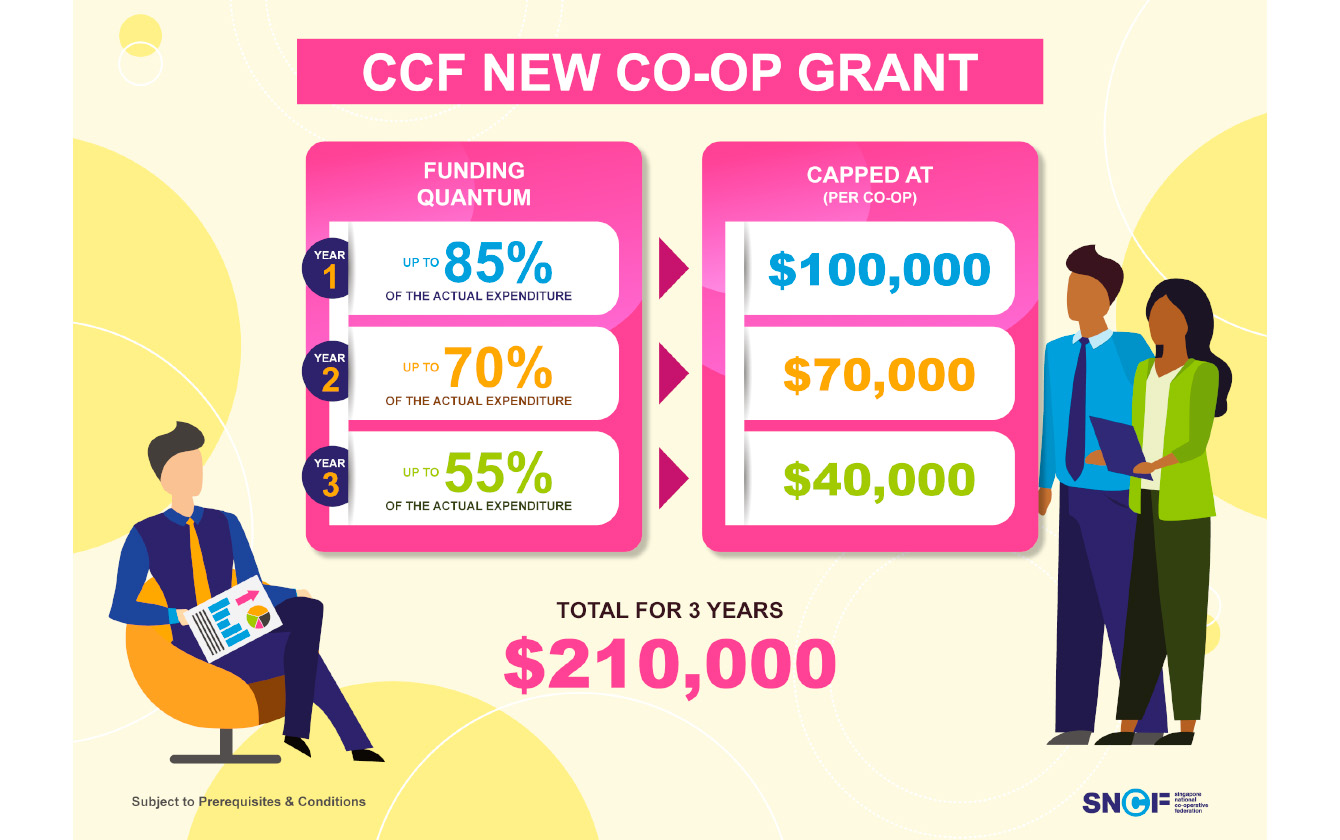

- We couldn't access startup capital from the CCF - after waiting 14 months to learn the outcome of our application for the New Co-op Grant, we were rejected because: (i) we had received government grants to hire interns during COVID-19 and (ii) based on our financial projections, they felt that we were not financially viable, despite us already operating for 3 years by that point and showing promising revenue streams.

- Difficulties with accessing other forms of capital - foundations like Toteboard which could have provided startup funds were unfamiliar with co-ops. Furthermore, a lack of awareness amongst Singaporeans further hindered our ability to raise startup funds by offering shares to new members.

- Difficulties with learning from co-op veterans - beyond the annual Co-operative Movement Night, there were limited opportunities to learn from experienced co-op veterans who could answer questions or offer advice. Thankfully, I managed to seek them out either by cold-calling or meeting them at ad-hoc events.

Current avenues of support for start-up co-ops in Singapore

But I also observed some positive developments that SNCF could build on to more effectively support co-op development in Singapore:

- SNCF engaged AGS to deliver mental wellness workshops for staff of different co-ops and training as part of their Emerging Leaders' program (i.e. internal procurement)

- Besides delivering the training, I received a full sponsorship to participate in the Emerging Leaders' program, which allowed me to network with young leaders from other co-ops and collaborate on projects (i.e. intentional networking and capability development)

- During the COVID-19 crisis, SNCF announced a waiver of the Central Cooperative Fund contribution (akin to a corporate income tax) and provided a one-off $2,000 cash grant for all co-ops.

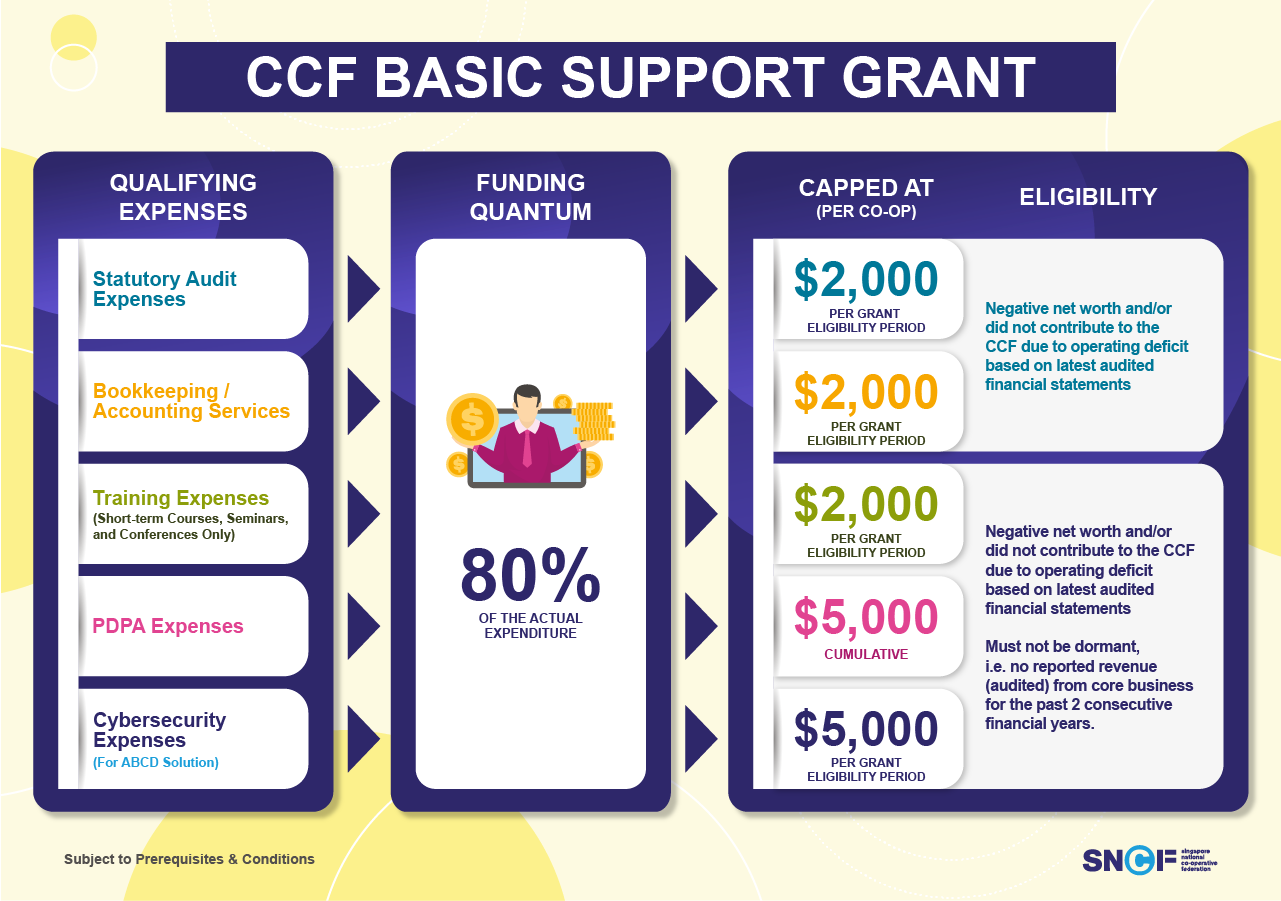

MCCY provides various grants to co-ops under their CCF framework for co-op education, training, research and professional services. However, most grants are only available to co-ops with positive net worth and contributions to the CCF - a criteria that most start-up co-ops may struggle to meet.

For co-ops with negative net worth or operating deficits, the CCF offers a Basic Support Grant, which provides smaller amounts to cover audit expenses, bookkeeping, training, PDPA alignment and cybersecurity expenses.

While these areas of support are generally useful, they may not help struggling co-ops with business support they need to turnaround their financial situation.

While it is fair that profitable co-ops contributing to the CCF receive more grant support, does it make sense to deny struggling co-ops additional help while well-off co-ops get more?

Systemic causes: The challenges faced on the ground are symptoms of 4 systemic issues

- There is inadequate support for incubating startup co-ops - particularly in crucial business skills such as: business model design, securing loans, grants and investments, market sizing and business coaching

- The landscape for capital access is still nascent - beyond the New Co-op Grant, there aren't many avenues for startup co-ops to access capital. While the CCF offers various grants, they may be more suited for stable co-ops than start-up co-ops. This contrasts with the landscape in the United States, where non-extractive lenders and patient equity firms provide capital for co-ops (more on this in Part 2).

Capital access is crucial because through my research talking to veteran co-operators and researching the financial statements of older co-ops, they often started with either: (i) significant loans or grants, (ii) a ready base of investors belonging to a particular religious faith or (iii) operated with volunteers to minimize operating costs.

- There is a lack of understanding and imagination of what co-ops are and what they can be - and this hinders our ability to imagine and innovate. Despite my business education at the National University of Singapore, co-ops were not covered in my studies. Public awareness of co-ops is low and some folks working in Singapore's co-op sector may be unfamiliar with models and innovations overseas.

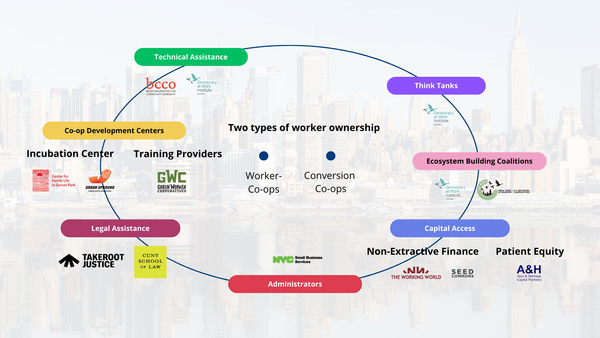

Furthermore, there is limited thought leadership on trends like platform co-ops, worker-owned co-ops and social technologies that support cooperative principles like Sociocracy; that could be deployed to Singapore's context for innovation in the co-op sector. - A thriving co-op ecosystem cannot rely solely on RCS and SNCF - observing the worker co-op ecosystem in New York (see ecosystem map in Part 2), it became clearer to me that the work of incubation, training, capital access and thought leadership require more than just two organizations.

Veteran co-operators could be valuable resources to help with some of these areas but opportunities for new co-operators to receive intentional mentorship from them are limited.

SNCF adopts a consultative approach by listening to ideas and concerns expressed by co-ops and can perhaps benefit from adopting a co-creation model, allowing passionate co-operators to initiate projects to grow the co-op movement with potential funding from CCF.

For example, beyond gathering learning topics that co-ops would like to be trained in, could CCF (through SNCF) give a small budget to ask interested co-operators to start peer learning circles? This way, progress in building the co-op movement does not have to be limited by the bandwidth of SNCF staff.

Mindset causes: There are two underlying mindsets that hinder the co-op movement in Singapore from thriving

In my humble view, the current systems and structures are shaped by deeper mindsets:

- Risk aversion by the CCF Committee - my interactions with RCS and the CCF Committee through SNCF during AGS' incorporation and subsequent grant application revealed a cautious, risk-averse approach, more akin to a government grantor safeguarding public funds than an incubator trying to encourage more co-ops to form.

This cautious stance could stem from RCS and the CCF being under the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (which also houses the office of the Commissioner of Charities, who also serves as the Executive Director of RCS), instead of the Ministry of Trade and Industry, which focuses on economic development and businesses.

Despite publicly communicating that co-ops are businesses, I found that RCS has a lower tolerance for risk, which is crucial for business innovation. They seem to prefer funding co-ops that are: (i) already profitable from Day 1, (ii) are operated by volunteers with minimal costs or (iii) can demonstrate a high chance of breaking even within three years.

"We need to be responsible to safeguard public funds," was what they said to us when our application for the New Co-op Grant was denied. It was difficult for me to accept, but I could understand where they were coming from, given their lenses as officers of MCCY.

These criteria are already challenging for most commercial startups, let alone for co-ops trying to do good and do well. RCS / the CCF may be better suited to fund SME owners without succession plans to convert their profitable businesses into worker-owned businesses, a concept known as a conversion co-op. - Singapore is an extremely achievement-oriented society - our young people, myself included, grow up in a culture of competition and achievement (e.g. scholarships, high-paying jobs, startups receiving large investments, and the Financial Independence Retire Early movement), who would want to start a co-op to share wealth and decision making?

When I was incorporating AGS, I shared it with a friend who was working in finance and he said: "Let me get this straight. You are doing all this work to setup an entity that you will co-own with people and share decision making, and not to maximize your own benefit?" To which I replied "Yes".

He looked at me in a funny way.

So, what can we do to improve the situation?

From August to November 2023, I worked at a 130-year old nonprofit in New York City through the US Department of State's Community Solutions Fellowship. This extended stay allowed me to explore the ecosystem supporting worker co-ops, talk to key stakeholders and better understand the issues I raised above.

I also gathered ideas for enhancing the co-op ecosystem in Singapore, which I'd like to put forth for RCS' and SNCF's consideration. Read part 2 for the lessons learnt from New York City and part 3 for the recommendations!